The Time by the Sea (4 page)

Read The Time by the Sea Online

Authors: Dr Ronald Blythe

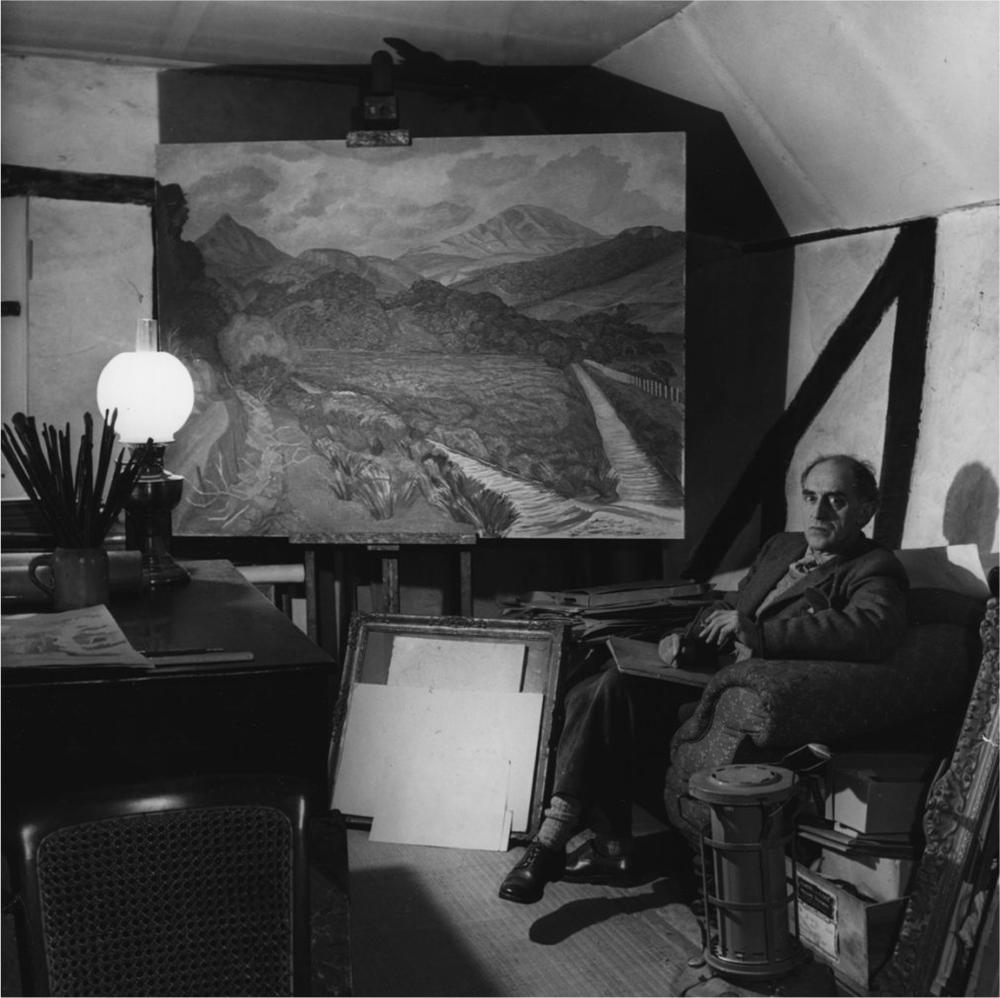

John Nash at Bottengoms

The time by the sea was also in part the first time deeply inland at Bottengoms, the home of John and Christine Nash, in the village of Wormingford, eight miles north of Colchester. Not unlike Imogen Holst’s dutiful flights to Thaxted in some ways; she to her mother, myself to giving a hand.

*

John Nash first came to Wormingford in June 1929. It was a wet, cold month ‘and I began to tell myself, this is no place at all …’ His wife Christine, always less easily depressed, sent a Judge’s postcard of the Mill to her mother with the message, ‘Good river scenery. Think we may stay here.’ Christine had discovered this particular working-holiday cottage through an

advertisement

in a local paper, and after a fruitless search around Framlingham for a suitable spot where John could paint. Throughout her married life, making such reconnaissances, often two or three each year, ‘were part of my job’, she said. ‘I don’t wish to boast, but it was only the places which I did not go to look at first that weren’t successful.’ During the early years of their

marriage

she had vetted these painting locations by bicycle, pedalling for long distances all over southern England,

and along the Gower peninsula, to find landscapes for John’s sketchbooks. These he would fill with pencil and wash drawings, complete with weather and colour notes, to be transcribed on to canvas during the autumn and winter. Like most young artists, they roughed it in their first attempts to make a living. Christine made no bones about it. ‘We very often had some awful places to stay. We were hard up, and really we had to endure a great deal, but we did have to have the right kind of scenery!’

They arrived at Wormingford Mill in fine style, however, due to the legacy of a sturdy 8.18 h.p. Talbot motor car which the previous owner, their dear friend Francis Unwin, used to drive round Brooklands. Unwin, one of the finest etchers of his time, had died from tuberculosis in Mundesley Sanatorium in Norfolk in 1925, and it was partly from a number of sad visits to him that John Nash had become attracted to East Anglia. His roots were in the Chilterns but family connections near Colchester had made him familiar with the Suffolk–Essex border. Paul Nash had actually taken part in the epic 1909 Colchester Pageant, and both myself and John were to wear his Tudor costume on fancy-dress occasions half a century later. But

Wormingford

in 1929 was entirely new to John and Christine, and when the sun came out by the flower-choked river, the village’s potential as a working-holiday location was evident. Some might say, ‘No wonder, with

Gainsborough

painting almost up to it and Constable almost down from it!’ But these celebrated associations meant curiously little to John. He himself was to become famous for what appeared to be an indifference to any art other than his own, and this not because of pride, but because of the way in which he was so entirely domi nated by his own vision of landscape. Sickert used to warn artists off the Stour Valley, saying it was a ‘sucked orange’, but John Nash painted it as though he had never heard of it being the most familiar river territory in English art.

The holiday house turned out to be a little clapboard bungalow adjacent to the Mill with a rustic fence and a view of the race. Box Brownie camera snapshots show an easel set up on the bridge, a punt containing a picnic and a portable gramophone, and John poling it through the reedy water, dressed in pyjama trousers and a jersey; Christine bathing and fellow artists sketching. The unpropitious June of 1929 had turned hot, and the long association with Wormingford had begun. He was thirty-six and had been an artist for seventeen years. In this comparatively short time he had taught himself to paint, to be a first-rate botanist and a good musician. He had achieved considerable recognition with his first show, had fought on the Western Front with the Artists’ Rifles, had as an official War Artist painted two of the greatest pictures of the fighting, had married a half-German, half-Scots Slade student named Christine

Kühlenthal, and was at this moment one of the leaders of the renaissance of book illustration which had taken place during the 1920s. He was a slight young man with large aquiline features and reddish-brown hair. His wife Christine was tall and dark. She no longer painted – ‘One artist in the house is enough’ – but was at this time active in Cecil Sharp’s English Folk Dance and Song Society, and her interest in movement and drama would, years later, be fulfilled in the many plays which she produced or acted in at Wormingford. Her ‘dancing’ step – like Imogen Holst’s, a leggy kind of gracefulness – remained with her until old age – and I always loved the way in which she would take off for a long walk with never a thought about the distance or the weather. Once the two of us walked from Bottengoms to Stoke-

by-Nayland

in thin rain, and we regularly walked those perfect footpaths which meandered from the house to Sandy Hill, via the Grange, the mere and the high ground past the church. John used to call all this countryside ‘the Suffolk–Essex Highlands’ and he liked to surprise guests by taking them off to see such untypical East Anglian contours, but always by car, never on foot.

John and Paul Nash, and their sister Barbara, were the children of a Buckinghamshire lawyer, William Nash, who became the Recorder of Abingdon. All three were inspired by the Chilterns’ beechwoods and chalky escarpments, and by such strange phenomena as the

ancient tumuli known as Wittenham Clumps. They lived at Iver Heath, then the deepest countryside during those pre-First World War days. One of their aunts had been engaged to Edward Lear and it was at her house that John first became influenced by comic drawings, as well as by Lear’s pale and exquisite watercolours of his travels. Both Paul and John were ‘pointed’ to painting by literature, this and their profound understanding of both the mystery and the practical lie of the land. It was John’s first intention to become a writer, and he apprenticed himself as a teenager to a local newspaper, learning shorthand and trying to learn style. But in 1912 a friend of Paul’s, the artist Claughton Pellew, took him off on a walking tour in Norfolk, talked to him, showed him what he was really seeing, which was line and colour, not words and plots, and sent him home to Iver determined now to paint, not write. His father, hearing the news, said John, cleared a space on the dining table and said, ‘You had better do it here.’ Paul was studying at the Slade. Should John go to an art school? ‘No,’ advised his brother. ‘The teaching will destroy the special “thing” which you possess, so teach yourself.’ It was daring advice but it proved right. I always remember old Mr Nash’s making a space on the table and saying ‘Do it here’ when John used to make a space for me on his painting table just before setting off on his work-holidays, so that I could write. But writers don’t like north-facing studios, so I would find a sunnier

spot, although not confessing to this as I used to think that it would hurt his feelings to have his favourite worktop rejected. Ivy grew in a dense curtain across the studio windows and, when I tugged some of it off to let in light and view, John would murmur, ‘Poor ivy.’

John’s discovery of Wormingford was partly due to the suggestion of Sir William Montagu-Pollock that he would find much to excite him in East Anglia – hence Christine’s search for a painting place near

Framlingham

. Thus two quite casual invitations to the area were to have far-reaching consequences. Claughton Pellew’s made him a painter; Sir William’s eventually led him to Bottengoms. Such are the small incidents which define what we are and where we should settle. For the whole of the Thirties the Stour Valley alternated with Cornwall and other places as a working-holiday venue. During John and Christine’s second visit in the summer of 1930, the old Mill burned down, and the nice clapboard bungalow with it. John’s sister Barbara was staying with them and she told me how they managed to rescue some of his pictures from the flames, though not all. This experience resulted in spasms of acute

fire-anxiety

later on, when they would beg me never to burn paper or ‘run with the lamps’, something I would never do, having been brought up with oil lamps. Christine loved their soft yellow light and the heat they

generated

, and their tongues of flame, so Pentecostal and comforting. She put off having electricity for ages so

that she didn’t have to give them up. For me they were glowing reminders of childhood, with their paraffin scented wicks and ‘Swan’ glass chimneys. Later at Bottengoms there would be Aladdin lamps with mantels and fat, battered parchment shades.

For most of the time between the wars the Nashes were living at Meadle in Buckinghamshire. It was there that John did much of his remarkable wood engraving, where he began to make friends with great gardeners such as Clarence Elliott who owned the Six Hills Nursery at Stevenage, and where he painted a whole series of landscapes whose subtle mixture of

agricultural

realism and underlying poetry established him as an artist in the classic English tradition of Cotman and Girtin. In November 1935 tragedy broke into this disciplined existence and wrecked it. William, John’s and Christine’s only child, was killed in a car accident. He was nearly five, a little boy who had become part of their happiness in the water-meadows and lanes in and around Wormingford. Hardly knowing what to do, there was talk, as John put it, of selling the house at Meadle and building another near the river here. The need to recover from this disaster apart, they had begun to put down roots in the Stour Valley. There were new friends such as Adrian Bell the writer and his wife, who lived at Creems Farm at Wissington, and they would be nearer to old friends like the Cranbrooks at Great Glemham. In the event nothing happened; the pattern

re-established itself and the idea of moving was put in some kind of abeyance. ‘One day’.

Adrian Bell was some ten years younger than John, a loquacious and idealistic person whose trilogy,

Corduroy

, Silver Ley

and

The Cherry Tree

, had established him as one of the best rural writers of his day. John rented a cottage called The Thatch near Creems – and near the Fox Inn – and they saw a lot of each other. Once the local boys challenged them to bring a canoe down the Stour from Sudbury to Bures, the state of the river, due to the farming depression, the collapse of barge transport and neglect generally, making it

virtually

invisible here and there in mid-summer, so dense were the weeds, so overgrown the trees on its banks. Some of the now unwanted barges which John

Constable

had painted had been scuttled at Ballingdon, and lay just below the surface of the water like vast black motionless fish. John and Adrian

did

sail a canoe all this choked length, though with every imaginable difficulty. Bures bridge was lined with cheering lads as they passed beneath, hot, scratched, exhausted, but triumphant. In 1939 John and Adrian collaborated on a book,

Men and the Fields

, which was a work of homage to the farmers and farmworkers of England, particularly to those who, in those hard-up times, were struggling to hold together the semi-ruined agriculture of the Stour

Valley

. Both Adrian’s books and John’s paintings reflect what might be described as a lyrical realism, a deep

knowledge of farming plus a pleasure in the designs which, for many centuries, it had carved across the English landscape. For Adrian it was a peopled countryside; for John, a land of plants and shapes whose human occupation was explained in terms of workaday litter, binders, fencing, shepherds’ huts, gravel diggings and carts. There cannot be many villages like Wormingford and Wissington, and their environs, which have been the attention of two such excellent chroniclers.

Adrian Bell wrote in his diary,

August 1935

Picture seeking with John Nash. Found

something

much to his purpose in Kid’s Hole at the back of Green’s. The artists, man and wife, staying in Greens are stanced opposite here daily, doing a scene in which the Finch harvest-team figures, have to move every time wagon leaves stack. In a great hurry because last load being put on stack, and he hadn’t half finished horses and wagon. John wants to do a picture of the valley from under the elm, but dismayed by my warning him that he may find others sitting about.