The Vault (20 page)

Authors: Peter Lovesey

Pennycook nodded. He looked wretched now.

"How much are you paying to kill yourself? A hundred a day? Two hundred? Listen, my friend, we're not here to dump on you because you're on the needle. We're not even after the bloodsuckers who supply you, though someone had better be. We want the truth about your trip to Bath. How did you travel?"

He said in a low voice, "Bummed a lift from a mate of mine, didn't I?"

"You don't have wheels of your own?"

"Does it look like I would?

"This mate. Was he staying with you in Bath?"

"No chance. He was on his way to Bristol."

Diamond locked eyes briefly with Leaman. Here was another suspect without his own transport.

"How long were you there?"

"Went for the funeral and stayed till the weekend."

"Stayed where?"

"My uncle's gaff."

"The will hasn't been proved yet and they let you stay in his house?" Diamond said in surprise.

Pennycook looked away, out of the window, towards the helicopter on the lawn. "It weren't a case of letting me."

"Meaning what?"

"I fixed it, didn't I?" Now he gave Diamond his full attention, taking obvious pride in the guile he had used. "The bank are the executors, right? They got the front door key. They know he left the whole bloody lot to me. I told them it was Uncle's wish for some of his old mates to go back to the house for a jar or two after the funeral." He chuckled. "They couldn't argue with that. About eight guys came back, said they were his mates. I don't know who they were. He had no family apart from me. Anyway, I found some wine downstairs and handed out cheese biscuits. At the end I was supposed to lock up and return the key to the bank. They sent a geezer in a suit to make sure I did. I give them back their key and kept the key of the basement. So I could let myself in later and save some money putting up in Bath."

It rang true. The ingenuity of the heroin addict is well known. "Then what?"

"I already told you."

"You scouted around for an antiques dealer, and Peg was the obvious choice."

"Went to look at her place first. Took a walk around and give it the once-over. Then I give her a bell from Camden Terrace asking for a valuation. I knew she'd come."

"You let her pick out some plums."

"She got what she wanted. She could have had more, but she was playing it cool."

"How much cash changed hands?"

"Grand and a half."

"She carried that much?"

"No. She told me to call for it later."

"Later the same day?"

"Yeah."

Diamond's eyes widened. "Thursday evening? Did she now?" This was a detail neither he nor Leaman had included in their picture of events the evening Peg Redbird was murdered. "You went, of course?"

He shrugged. "What do you think?"

"What time was that?"

"Don't know. Don't keep track of time."

"After dark?"

"Yeah."

"That would have been later than eight-thirty, then. Was she alone?"

Pennycook seemed to sense that he was walking into quicksand. "She was bumped, wasn't she?"

"Let's talk about your actions that evening."

"I didn't touch her. I collected my dosh and cleared off back to Camden Crescent."

"Fifteen hundred pounds?"

"Like I said. That was the deal." His thin body was starting to shake. "Look, if you think I'm the one who stiffed her, you're bloody mistaken. She was all right when I left."

"Did you see anyone else?"

"In the shop? No."

"Outside? Anywhere near the place?"

The temptation to steer suspicion to someone else must have been strong. "Don't remember."

Diamond was as energised as if he had taken a jab from one of Pennycook's syringes. This was crucial evidence: someone who had visited Peg shortly before she was murdered. "You came to the shop some time after dark, but before ten, correct?"

Pennycook gave a perfunctory nod.

"Shape up. I'm trying to help you." Encouragement, followed immediately by warning words. "You're under strong suspicion of murder. What you're about to say could convince us you're not the killer."

There was some doubt whether Pennycook was about to say anything.

"Tell us all you can remember about that meeting you had with Peg Redbird."

"There's sod all to tell."

Not in Diamond's estimation. "You arrive at Noble and Nude to collect your money. You walked, I suppose?"

"Yeah."

"Try and remember Walcot Street. Was it quiet?"

"I told you I didn't see no one. Just cars."

"Cars going by, or parked outside?"

"Going by. Nothing was parked there."

"A van? You didn't notice a van?"

"You're not listening."

"So you got to the shop. Was it open?"

"Course it was, or how would I have got in?"

"She could have let you in. What was happening when you entered?"

"She was in there, facing me, behind a big desk with boxes on it. I said—"

"Hold on," Diamond stopped him. "The boxes. Tell us about them."

"There's nothing to tell. Boxes, I said."

"What were they made of?"

"One was wood, I think, polished wood, dark. She closed it when I come through the door. Locked it up."

Mary Shelley's writing box. "You're sure of that?"

"Sure of what?"

"That the box had been open?"

"I wouldn't say it if I didn't remember, would I?"

Diamond nodded mechanically, thinking that this squared with Ellis Somerset's statement. It meant that Pennycook visited Peg after Somerset had left. The hired van was no longer outside and the box was still open. "What size was it? The size of a box file? You know what a box file is?"

"Yeah. Thicker than that. Like two of them, one on top of the other."

"And you mentioned other boxes."

"Rusty old tins without lids. Two or three, up at one end of the desk."

"You don't recall seeing anything else on the desk?"

"Nothing on the desk."

There was just the suggestion of more to come. Diamond coaxed it out. "But some other thing caught your interest?"

"Yeah?"

"Something else you happened to notice."

"Oh, yeah. On top of the safe I saw some of the stuff I sold her. Two old pictures off the wall. Scenes."

This clinched it. He had come after Ellis Somerset had delivered the goods to Noble and Nude.

"Scenes?" repeated Diamond, testing him. "What kind of scenes?"

"I don't know. Old-fashioned stuff. Not my taste at all."

"You couldn't tell me the artist?"

"I know sod all about art. I was telling you what happened," Pennycook said in a tone suggesting he finally understood the importance of giving an account. "I tell her I've come for my money and she says yes, it's ready. She opens a drawer in her desk, takes out a key and opens the safe. She has the money ready in a brown envelope. Fifteen hundred, mostly in twenties. She asks me to count it, and I do. I say something about doing more business with her, how I'd give her a second chance when I got the probate. She doesn't say much. I reckon she wanted to get rid of me and close the shop."

"What made you think that?"

"Don't know really. She wasn't so talkative this time. But I got what I came for, so it didn't bother me. I cleared off back to Camden Crescent."

"And the street outside—was that the same? Nothing waiting?"

"If it was, I didn't see it."

Diamond looked towards Leaman. "Anything I missed?"

The sergeant shook his head.

"Right," said Diamond, turning back to Pennycook. "That was Thursday night. What happened to you since?"

"Since?" He frowned. "Is that important?"

A look from Diamond told him that it was.

"I stayed in Bath. Friday I had to visit the bank to sign some papers. I hung about the streets until late to see if I could buy some H for less than they charge here in Brighton. No chance. The bastards fix the price all over, the same as cigarettes, or bloody cornflakes."

"And then half of it is filler, talc or some such," Diamond commented. "So you spent Friday evening there. How about Saturday?"

"I came back here, didn't I?"

"What time?"

"I keep telling you, I got no sense of time."

Well, Diamond thought wryly, railway timetables were supposed to be the detective's salvation. "How did you travel? On the train?"

"You're joking. Thumbed it, didn't I?"

The budget of the drug addict didn't run to train fares.

Pennycook claimed he had hitchhiked to Southampton on a juggernaut lorry bound for the docks and from there along the coast roads to Brighton with a couple of students. He had got back some time in the early hours of Sunday and slept until the afternoon.

No alibi for Peg's murder or the attack on John Wigfull.

"During your time in Bath, did any other police officer question you about Thursday?"

Pennycook shook his head.

"Can you drive?"

"What?"

"You heard me. Have you ever had a licence?"

"Yeah, some time. What are you trying to pin on me now?"

"Filling in the gaps in your statement, that's all. Maybe you went for a drive in the country yesterday afternoon."

"What with, for Christ's sake? I got no wheels."

"I reckon you have, amigo. Somewhere in a garage round the back of Camden Crescent, there's a nice, shiny motor that old Si used to drive about in. I'd put money on it. In fact, we can check on our computer."

"It ain't mine yet, even if there is one," he pointed out.

"The house isn't yours, and that didn't stop you."

"Bog off, will you?"

Which, presently, they did.

Outside on the lawn, interested residents still stood around the helicopter. Diamond looked about him as if for an escape route. "Where's the nearest pub, do you reckon?"

Leaman looked surprised. "Do you need a drink after that, sir?"

"Anything but. I didn't fancy using his toilet."

They headed across the grass to the roundabout at the north end and spotted a pub sign a stone's throw away on Dyke Road. And they did have a quick beer.

"What did you make of him?" Diamond asked, on the way back to the helicopter. Any conversation had to be got through before they boarded.

"Typical junkie," said Leaman. "They'll do anything to get the stuff. Sell their own mothers. Anything. We don't have to dig deep for a motive. He needed cash. She had it stacked away in the safe, didn't she? We don't know how much. All there was when we opened it was a few antiques, letters and things."

"If he did kill her, he didn't help himself much talking to us," Diamond commented. "Admitting he was at the shop that night and going on about how desperate he was for cash in hand."

"He's not very bright, is he?" Leaman said. "His brain's gone soft."

"I don't agree. It's easy to confuse poor speech with low intelligence, but there are plenty of big achievers, artists, musicians, inventors, who prove that wrong. I've known druggies smarter than anyone I've met in the police. Brilliant people. They channel all their intelligence in one direction, that's the tragedy."

"So you don't rate him as a suspect?"

"Didn't say that, did I? I just said he's smarter than you think, and probably smarter than both of us. He's putting one over everyone—the bank, the taxman, his landlord, Brighton Deckchair Services. Why shouldn't he put one over us as well?" As they stooped to enter the wind funnel under the rotor blades, he shouted to Leaman, "You wouldn't catch a bright lad like Pennycook risking his life in one of these."

BACK IN BATH THAT Sunday evening, there was no better news of John Wigfull. He had not recovered consciousness. His closest relative, a brother, had travelled down from Sheffield and was at the bedside; the hospital were making arrangements for him to spend the night there.

The search of the fields around the scene of the attack had produced a number of lumps of wood that could conceivably have been used as clubs. They were being tested for bloodstains, but no one was optimistic that the weapon had been found. And the door-to-door enquiries had proved negative for witnesses, except a couple of people who remembered seeing a red car— Wigfull's, presumably—outside Westwood Manor late Saturday evening.

"How late?" Diamond asked the DI who was on the phone from Trowbridge.

"Ten-thirty was the first sighting, but it's a little-used lane, sir. The car could have been there some hours without being noticed."

Trying to be positive after he came off the phone, Diamond pointed out to Sergeant Leaman that this narrowed the time-span. He still firmly believed that the attack took place on Saturday in daylight, the direct result of Wigfull's questioning of suspects. The way to discover Wigfull's assailant was to go for broke and find the killer of Peg Redbird.

"Did John Wigfull do anything about her phone?" he asked Leaman.

"Her phone, sir?"

"The calls she made on the day of her death. If they can do it for my phone bill, they can do it for us, pronto. It's all routinely logged. The date, the time, the duration and, worst of all, the charge."

Til see to it."

A little later, Leaman reported that British Telecom would supply a list by the morning. This young sergeant's support was a real asset. Together, they went down to the canteen for supper.

The ever-cheerful, ever-saucy Pandora greeted them with an offer of roast lamb at half the price listed on the board.

"What's the catch?" Leaman asked.

"The catch," said Diamond, "is that it was cooked this morning. It's as dry as Deuteronomy."

Pandora dipped a formidable ladle into a pot. "Not when I pour some of this delicious gravy over it. See, you're slavering at the mouth already, Mr D, or is it me you're drooling over?"

"That's a leading question."

"Lead me anywhere you like, darling. My shift ends at ten."

He was too wary of double meanings to say anything about Pandora's shift. "Thanks. I'll see if I survive the roast lamb."

They spotted Keith Halliwell sitting alone, staring ahead with a look that could have stripped paint. It was quickly apparent that Frankenstein jokes were not the cure. Canteen humour palls after a long, unproductive day.

He said, "If we can talk shop for a moment, sir, I'd like to put out that appeal tomorrow—for information on the two labourers known as Banger and Mash. I prepared a press release. Would you mind giving it the OK?"

In the last hours the mystery of the bones in the vault had gone as tepid as the half-price lamb, but Diamond somehow conjured up some interest. "No more progress, then?"

"I don't expect any until someone's memory is jogged."

"Right you are. I'll run an eye over it before I leave tonight. How are the press treating you?"

"It isn't so crazy as yesterday. They realize there isn't any mileage in this story now we've finished in the vault."

"There's an unexplained death."

"Yes, but a nineteen-eighties unexplained death. The Franken-

stein

connection doesn't hold up."

Diamond's thoughts swung back to the other case. "It's mighty odd that we have links with the killing of Peg Redbird."

"The writing box?"

"Yes. Apparently Mary Shelley's copy of Milton came out of it, so there's some chance the box actually belonged to her. Joe Dougan seems convinced."

"What happened to it?"

"The box? Don't know. It was gone from Peg's desk by the time we arrived on the scene. Joe could have nicked it and hidden it, with the idea of taking it back to America. Or someone else may have understood its value and carted it away."

Leaman reminded him, "It was still on the desk when Penny-cook came for his money."

"It was still there when Joe decided to quit at eleven."

"According to Joe."

"According to Joe, yes."

Doubts of Joe's testimony hung in the air.

"Was the box worth killing for?" asked Leaman.

Diamond put down his knife and fork. The lamb had the texture of car tyres. "To you or me, probably not. To someone who has set his heart on owning it, yes. You had a unique object there. Remember the last Commandment."

Leaman and Halliwell exchanged an uneasy look. They didn't know which was the last Commandment and they wouldn't have expected Diamond to know, either. This was the second reference to the Old Testament in a few minutes from a man not noted for his piety.

" 'Thou shalt not covet.' They weren't thought up on the spur of the moment, those Commandments."

Sergeant Leaman was puzzled by the reference. "Isn't coveting when you get a craving for someone else's property? I thought the writing box was up for sale."

"Well, yes." Diamond retreated slightly. "In theory it was, but she wasn't willing to part with it. And Joe was extremely keen to own it. I call that coveting."

"I see," said Leaman in a tone that was not quite convinced. "It's not the Commandment I would have thought of."

" 'Thou shalt not kill'?" said Halliwell.

"We could all have thought of that," said Diamond.

"So is Joe a murderer?" said Leaman.

Diamond answered opaquely, "I can't at the moment think of anyone with a stronger interest in possessing the writing box. And tomorrow morning, he's off to Paris," he added in a fatalistic tone.

Halliwell became animated. "Can't we catch him with it?"

"He'll have arranged for it to be shipped, if he

is

our man. Unless..." The words trailed away for a moment while a better hypothesis fell into place. "... unless his wife took it with her. Suppose she didn't walk out on him that night. Suppose they planned it together over that meal they had in Brock Street. She would go ahead with the writing box. He would create a smokescreen by pretending she was missing. Days later, he'd announce that she had turned up in Paris and he was joining her."

"Big thing for a woman to lug about," said Leaman.

Diamond shook his head. "It wasn't that heavy. It was a woman's writing case, remember. It was designed to be portable. And she had no other luggage."

"Sir, are you saying his wife was in on the murder?" Leaman asked in a tone that showed he was not persuaded. He was so new to Diamond's inner circle that he didn't realise the risks he was taking.

"I don't know what passed between them. He could have told her anything."

"So Mr Wigfull was right to be suspicious of Joe Dougan."

That was tactless in the extreme. In view of Wigfull's condition, Diamond chose to ignore it. "Is the ACC about?"

"She was in most of the day," said Halliwell. "Wants to be part of the action, by the look of it."

"I'd better see if she's there."

He got up, leaving Leaman and Halliwell bemused. For Peter Diamond actually to go looking for the Assistant Chief Constable was about as likely as rocking-horse manure.

SHE WAS dictating letters into a tape-recorder in her office. "Peter, come in. How's it going?"

The use of his first name still grated. She was so new in the job.

He summarised the day's work: the questioning of Ellis Somerset at the Antiques Fair; the finding of Wigfull's car; the visit to the scene of the attack; the interview with Joe; the news that Donna Dougan was alive and shopping in Paris; and the helicopter trip to Brighton to establish that Ralph Pennycook had visited Peg Redbird on the evening she was killed.

Georgina complimented him, "You've quartered the ground pretty thoroughly by the sound of it."

She got up, and for a moment he thought she was about to make a move towards the whisky cupboard, but she only went to the window and closed it.

"Draughty. The days are hot, but have you noticed how temperatures are starting to drop in the evenings now?"

"Yes." And something to warm our insides wouldn't come amiss, he thought.

"So you've interviewed all the people who spent time with Miss Redbird on the evening she was killed?"

"There was another, I believe."

"Oh?"

"Peg had an appointment with someone else that evening. 'Other business', Ellis Somerset called it when he told me. She was trying for a quick sale of the Blakes she bought from Camden Crescent. She upset Somerset the way she put it, teasing him about expecting an offer that night."

She gave a prim tug at her ear lobe. "An offer of a sexual character?"

"That was the implication."

"Did Somerset have a relationship with her, then?"

"He says not. He was keen, he admits, but she kept him at arm's length. So he was jealous when she spoke of this other meeting late in the evening."

"Are you sure he wasn't making this up?"

"Why should he?"

"It's one of the oldest tricks of all, inventing an extra suspect to deflect suspicion."

There was a glint in Diamond's eye. Georgina had made a telling point. "You're assuming Somerset killed her?"

"He was the last to see her alive, wasn't he?"

"True."

"Then he's got to be in the frame."

"Yes, but what's his motive? Anger at being jilted?"

Georgina smiled. "I do believe you're a romantic, Peter. No, I don't think he'd kill her for that. The motive is theft. That writing box had been revealed as valuable, and so had the watercolours from Camden Crescent. He was in on the secret, but he wasn't getting a share of the loot."

He let Georgina's theory shake down with his own.

"Have you got a piece of paper, ma'am?"

"Paper? What for?"

"I'd like to show you something."

"Will this do?" She handed him the pad she kept by the phone.

"This is my shopping-list," he explained, while he was writing.

He slid the pad back across the big desk. "Her visitors that evening."

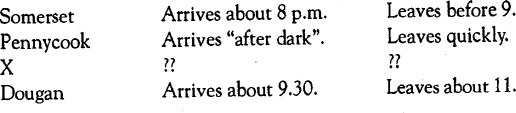

She studied what he had written:

The ACC examined the list for some time. "This 'X' is the mysterious art fancier, if we believe in his existence?"

"Yes."

"And you believe Pennycook visited her after Somerset?"

"Can I tell you why? He's hopeless about times, but I did establish that it was dark when he called at the shop for his money. That's after 8.30 this time of year. She was alone, then, so Somerset had left. The watercolours were stacked on the safe, so we know he'd already delivered them."

"That makes sense," she admitted.

"By the time Dougan arrived at 9.30, Peg was no longer there, if he's speaking the truth. She could have been dead."

"You're telling me now that Pennycook was the last to see Miss Redbird alive?"

"Pennycook, or X. Pennycook didn't stay long. She handed him the money, he counted it and left. He said she wasn't talkative. She seemed to want to get rid of him."

"When exactly did Pennycook leave?"

He spread his hands.

"But he'd gone by 9.30, when Dougan arrived?"

"That's my reading of it."

"He'd left, and so had Miss Redbird, apparently. Yet you have X, the mystery man, slotted in between Pennycook and Dougan. That's impossible, isn't it? The time is too short."

"No, ma'am, I don't think it is. The way I see it, she finished with Pennycook as quickly as she could and went for her meeting with X. She wasn't seen again."

"She went out?"

"Taking the pictures she intended to sell."

The ACC scrutinised the list again. "Why would she have gone out when she knew Dougan was coming back?"

"She didn't know how soon. She may have thought she was safe for a couple of hours."

She put her hand nervously to her tight-curled silver hair as if to check that it was still there. "Do you have a theory who X might be?"

"Yes, I do, ma'am. Someone with a special interest in early English watercolours. Councillor Sturr."

Sharply, she said, "What do you know about John Sturr's interests?"

The remark hit him hard. In Georgina's eyes, he was a yob who knew sod all about art. She wasn't far wrong, but he didn't like it taken for granted. "He showed me some of his pictures at the Victoria Gallery last week."

"Showed you? Personally?"

Nonchalantly he said, "A private view. Not the most exciting stuff I've seen. He claims to have one of the best private collections in the country, as I'm sure you know. If I were selling a couple of Blakes locally, that's who I'd approach."

The muscles at the side of her face tightened. "This is not a good way to go, Peter."

"I know." He left unsaid his determination to go on, regardless. She could see it in his look.

She said, "You're not seriously suggesting a member of the Police Authority is implicated in these events?"

"I'd like to know if Mr Sturr was in communication with Peg Redbird last Thursday."

"But he spent last Thursday evening at my house. The dinner party I gave. You know that."