The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 (94 page)

Read The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 Online

Authors: Margaret MacMillan

Tags: #Political Science, #International Relations, #General, #History, #Military, #World War I, #Europe, #Western

Berchtold still needed formal approval from the old emperor and so

on the morning of 20 July, accompanied by Hoyos, he travelled out to Ischl. Franz Joseph read the document through and commented that some of the conditions it contained were very harsh. He was right. The ultimatum accused the Serbian government of tolerating criminal activities on its soil and demanded that it take immediate steps to end them, including dismissing any civilian or military officials Austria-Hungary chose to name, closing down nationalist newspapers and reforming the education curriculum to get rid of anything that could be construed as propaganda directed against Austria-Hungary. More, the ultimatum infringed Serbia’s sovereignty. In two clauses, which in the end were to be the sticking point for Serbia, it was ordered to accept the participation of the Dual Monarchy in suppressing subversion within Serbia’s borders and in the investigation and trial of any Serbian conspirators responsible for the assassinations. The Serbian government was to be given forty-eight hours to respond. The emperor nevertheless approved the ultimatum as it stood. Berchtold and Hoyos stayed to lunch and returned to Vienna that evening.

78

On 23 July Giesl, Austria-Hungary’s ambassador in Belgrade, made an appointment to visit the Foreign Ministry late that afternoon. Pašić was away campaigning so Giesl was received by Laza Paĉu, the Finance Minister, who was chain-smoking. Giesl started to read out the ultimatum but the Serbian interrupted him after the first sentence, saying he did not have authority to receive such a document in Pašić’s absence. Giesl was adamant; Serbia had until 6 p.m. on 25 July to make its response. He laid the ultimatum on a table and left. There was a deathly silence as the Serbian officials absorbed the contents. Finally, the Minister of the Interior spoke: ‘We have no other choice than to fight it out.’ Paĉu rushed to the Russian chargé d’affaires and begged him for Russia’s support. The regent Prince Alexander said that Austria-Hungary would meet ‘an iron fist’ if it attacked Serbia and the Serbian Defence Minister took preliminary steps to prepare for the country’s defence. For all the defiant rhetoric, however, Serbia was in a poor condition to fight. It was still recovering from the Balkan wars and a large part of its army was in the south holding down the unruly new territories it had acquired. Over the next two days its government desperately sought to escape the doom that hung over Serbia. It had faced Austria-Hungary’s anger before in the Bosnian crisis and in the First and Second Balkan Wars yet it had

always managed to survive through a combination of its own concessions and pressure on Austria-Hungary from the Concert of Europe.

79

Pašić arrived back in Belgrade at 5 a.m. the next morning, ‘very anxious and dejected’ according to the British chargé d’affaires. Plans were being made for the government to leave the capital and to mine the bridges over the Sava which marked the border with Austria-Hungary. The Russian ambassador reported that funds from the national bank and government files were being shipped out and that the Serbian army had started to mobilise. The Serbian cabinet met for hours on 24 July trying to draft a response to the ultimatum; it ended by accepting all the demands except the two which gave Austria-Hungary the right to interfere in Serbia’s internal affairs. The Serbians tried to buy time by asking Vienna to extend the deadline but Berchtold curtly told their ambassador that he expected a satisfactory reply – or else. Pašić also sent out urgent requests to Europe’s capitals for support. He seems to have hoped that the other great powers, France, Britain, Italy and Russia but possibly even Germany, would come together as they had before in crises in the Balkans to impose a settlement. The responses, if they came at all, were discouraging. In Serbia’s immediate neighbourhood, Greece and Rumania made it clear that they were unlikely to come its aid in a war with Austria-Hungary while Montenegro, true to form, made vague promises which could not be relied upon. Britain, Italy and France advised that Serbia do its best to compromise and in those early days showed little inclination to mediate.

The only power which offered anything stronger was Russia and even there the message it sent was mixed. On 24 July Sazonov told the Serbian ambassador in St Petersburg that he found the ultimatum disgusting and promised Russia’s help, but said that he would have to consult with the tsar and with the French before he could offer anything concrete. If Serbia decided to fight, the Russian Foreign Minister added helpfully, it would be wise to go on the defensive and retreat southwards. On 25 July, as the deadline approached, Sazonov had a more robust message for the ambassador. Russia’s key ministers had now met with the tsar and decided, so it was reported to Belgrade, ‘to go to the limit in defense of Serbia’. While this still did not constitute a firm promise of military support, it may well have encouraged the Serbian government as it prepared its final reply to Austria-Hungary.

Belgrade was very hot that day and the city reverberated with the sound of drums beating to call up the conscripts.

80

Among the Entente nations, whose leaders had not really focussed up to this point on the developing crisis in the Balkans, the reaction to the ultimatum was one of shock and dismay and they scrambled to work out their own positions. Poincaré and his Prime Minister Viviani were by now on board a ship in the Baltic and were having difficulties in communicating with Paris and with their allies. Separately Grey in London and Sazonov in Russia asked Austria-Hungary to extend the deadline. Berchtold refused to budge.

Reactions were different in Germany and Austria-Hungary, where nationalist and military circles greeted the news with enthusiasm. The German military attaché in Vienna reported, ‘Today, a heightened mood dominates the war ministry. Finally a sign of awakening energy in the monarchy even if for now only on paper.’ The main fear was that, yet again, Serbia would wriggle out of its punishment. From Sarajevo on the day the deadline was to expire the military commander wrote to a friend: ‘With what pleasure and bliss would I sacrifice my old bones and my life, if it will successfully humble the assassin-state and put an end to this harbour for murderous children – God grant us only that we stay resolute and that today at 6 p.m. in Belgrade the die rolls in our favour!’

81

The Serbian reply which Pašić brought to Giesl shortly before the deadline granted this wish. While its tone was conciliatory, the Serbian government refused to concede on the crucial points of Austria-Hungary’s interference in Serbia’s internal affairs. Saying, ‘we place our hopes on your loyalty and chivalry as an Austrian general’, Pašić shook Giesl’s hand and left. The ambassador, who had already assumed the reply would be unsatisfactory, gave the document a cursory glance. His instructions from Berchtold were clear: if Serbia did not accept all the conditions, he must break off diplomatic relations. In fact he had already prepared the note doing so. While a messenger took it to Pašić, Giesl burned the embassy code books in his garden. He, his wife and his staff, with one small piece of hand luggage each, made their way by car to the railway station through streets jammed with crowds. A large part of the diplomatic corps had come to see them off. Serbian troops guarded the train and as it puffed out one shouted to the departing military attaché:

‘Au revoir à Budapest.’ At the first stop in Austria-Hungary, Giesl was called to the platform to take a phone call from Tisza. ‘Must it really be like this?’ the Hungarian asked. ‘Yes’, replied Giesl. In Ischl far to the north Franz Joseph and Berchtold were anxiously waiting for news. Just after 6 p.m. the War Ministry in Vienna phoned to say that relations with Serbia had been ruptured. The emperor’s first reaction was ‘So after all!’ but after a silence he mused that breaking off relations need not necessarily lead to war. Berchtold also clutched briefly at that straw but he had now set in motion forces which he did not have the strength of character to resist.

82

Conrad, who had been leading the hawks, suddenly demanded a delay in Austria-Hungary’s formal declaration of war until the second week of August on the grounds that his armies would not be ready until then. Berchtold, who feared that any delay would give time for the other powers to insist on negotiations and who was also under pressure from Germany to move quickly, refused and on 28 July Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, although the serious fighting was not going to start until the second week of August. Austria-Hungary and Germany, with help from Serbia, had got Europe to this dangerous point. Much now depended on what the other powers did. In the next week Europe was to hang between war and peace.

CHAPTER 19

The End of the Concert of Europe: Austria-Hungary Declares War on Serbia

In the middle of July that indefatigable couple, Beatrice and Sidney Webb, were at a Fabian summer camp talking about Control of Industry and Insurance and complaining about an unruly group of Oxford students who sang revolutionary songs and drank too much beer. Troubles on the Continent caught their attention from time to time but, as Sidney said, war among the powers ‘would be too insane’.

1

Indeed, the main issue that was worrying foreign offices and the press across Europe for most of the month was not Serbia but the deteriorating situation in Albania, where its new ruler, a hapless German prince called William of Wied, was facing widespread revolt and civil war. The Austrian ultimatum to Serbia on 23 July was the first indication for most Europeans that a much more serious confrontation was shaping up in the Balkans, and when Serbia’s reply was rejected by Vienna on 25 July, concern started to turn to alarm. Harry Kessler who had been spending a pleasant few weeks visiting friends in London and Paris, among them Asquith, Lady Randolph Churchill, Diaghilev and Rodin, began to think seriously about heading back to Germany.

2

Yet many of those close to the centres of power assumed that war

could still be avoided, as it had been in other similar crises. On 27 July, Theodor Wolff, the editor of the

Berliner Tageblatt

, one of Germany’s leading newspapers, took his family on their annual holiday to the Dutch seaside, although he himself returned to Berlin. Jagow, the Foreign Secretary, told him that the situation was not critical, that none of the major powers wanted war, and that Wolff was quite safe to leave his family in the Netherlands. Even those whose business was fighting found it difficult to believe that this time the crisis was a serious one; as a member of Germany’s general staff wrote in his diary after the war had broken out, ‘If anyone had told me then that the world would be ablaze a month later, I would have only looked at him with pity. For, after the various events of the last years, the Morocco-Algeciras crisis, the annexation crisis of Bosnia-Herzegovina, one had slowly but surely lost the belief in war.’

3

Even in Russia, where trouble in the Balkans tended to raise alarms, reaction to the news of the assassination was marked at first more by indifference than apprehension. The Duma had already risen for the summer and there seemed no need to call it back. The Russian ambassador in Vienna assured his government, ‘There is already reason to suppose that at least in the immediate future the course of Austro-Hungarian policy will be more restrained and calm.’

4

Nevertheless, like its ally France and its rivals Germany and Austria-Hungary the Russia of 1914 was apprehensive about the future. Britain did not seem anxious to conclude a naval agreement and Persia remained a source of tension. Russia was also engaged in a struggle with Austria-Hungary for influence over Bulgaria, which it appeared to be losing, and it faced challenges from both its own ally France and Germany in the Ottoman Empire. A ‘Teutonic ring’, an influential St Petersburg newspaper had warned at the end of 1913, ‘threatens Russia and the whole of Slavdom with fatal consequences …’

5

In May the chief of Russia’s police forces had passed on a warning to the Russian general staff that his spies were telling him that Germany was ready to find a pretext to strike while it still had a chance of winning.

6

For the Russian government the domestic situation was even more troubling than the international; in May and June the value of the rouble was going down and there were worries about a coming depression. There had been strikes and demonstrations all year across Russia and July was going to see more than in any previous month.

7

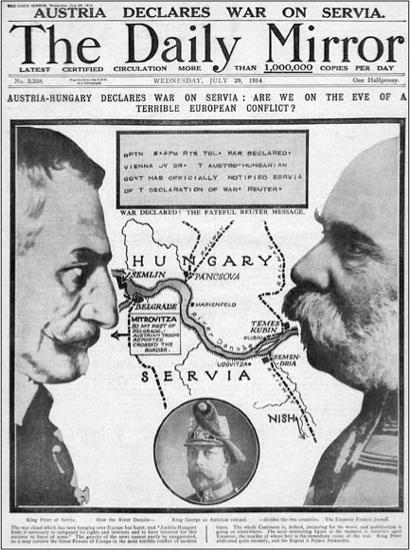

19. As the headline suggests – ‘Are we on the eve of a terrible European conflict?’ – the crisis unfolding in the Balkans in July 1914 took most of Europe by surprise. With the death of the Archduke, Austria-Hungary issued an ultimatum to Serbia, designed to be unacceptable. The Serbian government went a considerable way to accepting its terms but on 28 July Austria-Hungary declared war. Here King Peter I of Serbia faces the Emperor Franz Joseph while in the small insert, the British king George V appears dressed in the uniform of an Austrian colonel, a sign of older and now vanished friendships.