The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 (98 page)

Read The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 Online

Authors: Margaret MacMillan

Tags: #Political Science, #International Relations, #General, #History, #Military, #World War I, #Europe, #Western

In Italy, however, the streets were quiet and the British ambassador reported that opinion condemned both Serbia’s role in the assassination and what was seen as an overly harsh reaction by Austria-Hungary. The Italian public was waiting, he noted, in an ‘attitude of somewhat anxious expectancy’. The government, in his view, was looking for a plausible reason to evade the obligations of its membership of the Triple Alliance.

67

The dilemma for the Italian government was that it did not want to see Austria-Hungary destroy Serbia and so be supreme in the Balkans but, on the other hand, it did not want to antagonise its alliance partners and particularly Germany. (The Italians like many other Europeans had a healthy, even exaggerated respect for German military power.) An actual European war presented a further problem still: if Germany and

Austria-Hungary won, Italy would be left even more at their mercy and become a sort of vassal state. War on the side of the Dual Alliance would also be unpopular at home, where public opinion still tended to view Austria-Hungary as the traditional enemy which had bullied and oppressed Italians just as it was now doing with Serbians. A final consideration was Italy’s own weakness. Its navy would be decimated if it had to fight the British and French navies and its army badly needed a period of recovery after the war with the Ottoman Empire over Libya. Indeed, Italian forces were still fighting a strong resistance in their new North African territories.

68

San Giuliani, Italy’s wise and experienced Foreign Minister, was spending July in Fiuggi Fonte in the hills south of Rome in a vain attempt to cure his debilitating gout. (The local waters were famous for curing kidney stones as well and had a testimonial from Michelangelo, who said it cured him of ‘the only kind of stone I couldn’t love’.) The German ambassador to Italy visited him there on 24 July to pass on the details of the ultimatum. Despite considerable pressure from both Germany and Austria-Hungary, San Giuliani took the position then and in the ensuing weeks that Italy was not obliged to enter any war which was clearly not a defensive one but that it might decide to join in under certain circumstances – the offer of territory inhabited by Italian speakers from Austria-Hungary in particular. And if Austria-Hungary made gains in the Balkans Italy would have to be compensated as well. On 2 August the government of Austria-Hungary, which rudely referred to Italians as unreliable rabbits, reluctantly gave way to pressure from Germany and made a vague offer of compensation of territory, not including, however, any from Austria-Hungary itself and only if Italy entered the war. The following day, Italy declared that it would remain neutral.

69

In Britain during that last week of July, public opinion was also deeply divided with both the strong radical wing of the Liberal Party and the Labour Party opposed to war. When the Cabinet met on the afternoon of Monday 27 July it was split down the middle. Grey, equivocating, did not propose a clear course of action. On the one hand, he said, if Britain failed to join France and Russia,

we should forfeit naturally their confidence for ever, and Germany would almost certainly attack France while Russia was mobilising.

If on the other hand we said we were prepared to throw our lot in with the

Entente

, Russia would at once attack Austria. Consequently our influence for peace depended on our apparent indecision. Italy, dishonest as usual, was repudiating her obligations to the Triplice on the ground that Austria had not consulted her before the ultimatum.

70

After the meeting Lloyd George, the influential Chancellor of the Exchequer, who was still in the camp of those who wanted peace, told a friend ‘there could be no question of our taking part in any war in the first instance. He knew of no Minister who would be in favour of it.’

71

Across the Channel some of those decision-makers who had been so bellicose were briefly having second thoughts. Now back in Berlin, on 27 July the Kaiser thought that the Serbian reply to the ultimatum was acceptable. Falkenhayn, the War Minister, wrote in his diary, ‘He makes confused speeches. The only thing that emerges clearly is that he no longer wants war, even if it means letting Austria down. I point out that he no longer has control over the situation.’

72

The tsar sent Sazonov a note suggesting that Russia join forces with France and Britain, and perhaps Germany and Italy, for an attempt to preserve the peace by persuading Austria-Hungary and Serbia to take their dispute to the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague: ‘Maybe time is not lost yet before fatal events.’

73

Sazonov also undertook to have direct conversations with Austria-Hungary and from Berlin Bethmann advised Germany’s ally to take part, more it seems to have the opportunity to put Russia in the wrong before domestic opinion in the Dual Alliance than for peace.

Although the Kaiser and perhaps Bethmann continued to grasp at straws as they whirled past on the strong currents that were now running, the prevailing mood among the German leadership by this point was that war was inevitable. They were also persuading themselves that Germany was the innocent party. Moltke in a grim memorandum he wrote on 28 July said Russia was bound to mobilise when Austria-Hungary attacked Serbia and Germany would then be bound to come to the aid of its ally with its own mobilisation. Russia would respond by attacking Germany and France would come in. ‘Thus the Franco-Russian alliance, so often held up to praise as a purely defensive compact,

created only in order to meet the aggressive plans of Germany, will become active, and the mutual butchery of the civilised nations of Europe will begin.’

74

The talks between Russia and Austria-Hungary duly started on 27 July only to be broken off again the next day when Austria-Hungary, under pressure from Germany to move quickly, declared war on Serbia.

75

Austria-Hungary’s declaration of war on Serbia would have been amusing if it had not had such tragic consequences. Since he had melodramatically closed his embassy in Belgrade, Berchtold found himself at a loss as to how to deliver the news to Serbia. Germany refused to be the emissary since it was still trying to give the impression that it did not know what Austria-Hungary was planning and so Berchtold resorted to sending an uncoded telegram to Pašić, the first time that war had been declared that way. The Serbian Prime Minister, suspecting that someone in Vienna might be trying to trick Serbia into attacking first, refused to believe it until confirmation had come in from Serbian embassies in St Petersburg, London and Paris.

76

In Budapest Tisza gave a passionate speech of support for the declaration in the Hungarian parliament and the leader of the opposition cried out, ‘At Last!’

77

When Sukhomlinov heard the news at a dinner party in St Petersburg, he said to his neighbour, ‘This time we will march.’

78

On the night of 28 July Austrian guns on the north shore of the Sava fired shots at Belgrade. Europe had a week of peace left.

CHAPTER 20

Turning Out the Lights: Europe’s Last Week of Peace

Austria-Hungary’s declaration of war on Serbia on 28 July turned what had been Europe’s increasingly firm march towards war into a run over the precipice. Russia, which made no secret of its support for Serbia, was likely to threaten Austria-Hungary in response. If that were to happen, Germany might well come to the aid of its ally and so find itself at war with Russia. Then, given the nature of the alliance systems, France might be obliged to enter on Russia’s side. In any case, although the German war plans were secret, the French already had a fairly clear understanding that Germany had no intention of waging a war on Russia alone but would attack in the west as well. What Britain and Italy as well as smaller powers such as Rumania and Bulgaria would do was still an open question, although all had existing friendships and ties to the potential belligerents.

The Austrian writer Stefan Zweig was taking a holiday near the Belgian port of Ostend, where he remembered the mood was as carefree as every other summer. ‘Visitors enjoying their holiday lay on the beach in brightly coloured tents or bathed in the sea, the children flew kites, young people danced outside the cafés on the promenade laid out on the harbour wall. All imaginable nations were gathered companionably

together there.’ Occasionally the mood darkened when the newspaper sellers shouted out their alarming headlines of threats of mobilisation further to the east or the visitors noticed more Belgian soldiers about, but the holiday spirit soon returned. Overnight, though, it became impossible to ignore the clouds that were gathering over Europe. ‘All of a sudden’, Zweig recalled, ‘a cold wind of fear was blowing over the beach, sweeping it clean.’ He packed up hastily and rushed homewards by train. By the time he reached Vienna the Great War had started. Like thousands upon thousands of his fellow Europeans he had trouble believing that Europe’s peace had ended so quickly and so finally.

1

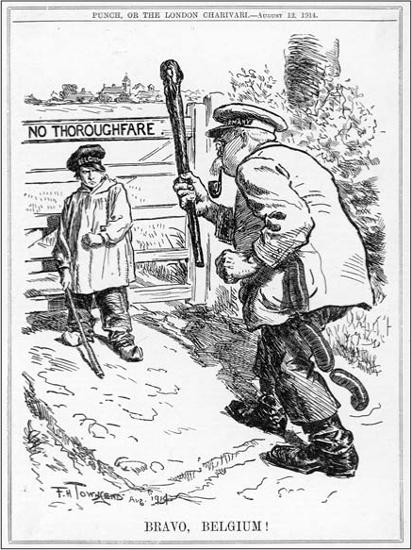

20. The German plan, usually known as the Schlieffen, assumed that Germany would fight a two-front war against France and Russia. To knock its enemy in the west out quickly, the German military planned a quick advance into Belgium and northern France. Although Germany called on Belgium to let the German armies pass through peacefully, the Belgian government decided to resist. This both slowed down the German advance and, even more importantly, persuaded the British to enter the war to defend brave little Belgium.

The sudden deterioration in Europe’s international relations set off a round of frantic last-minute manoeuvres in Europe’s capitals. Cabinets held emergency meetings around the clock; lights burned all night in foreign offices; even rulers and the most eminent of statesmen were dragged out of their beds as telegrams came in and were decoded; and junior officials slept on camp beds by their desks. Not everyone in a position of authority wanted to avoid war – think of Conrad in Austria or Moltke in Germany – but as exhaustion crept up on the decision-makers so did a dangerous feeling of helplessness in the face of doom. And all were concerned to demonstrate that their own country was the innocent party. This was necessary both for domestic consumption, in order to bring the nation united into any conflict, but also to win over the uncommitted powers, such as Rumania, Bulgaria, Greece or the Ottoman Empire in Europe, and, further away, the great prize of the United States with its manpower, its resources and its industries.

The morning after the Austrian declaration of war, on 29 July, Poincaré and Viviani landed at Dunkirk and immediately made their way to Paris, where they were greeted by a large and enthusiastic crowd which shouted ‘Vive la France! Vive la République! Vive le Président!’ and, occasionally ‘To Berlin.’ Poincaré was thrilled. ‘Never I have I been so overwhelmed’, he wrote in his diary. ‘Here was a united France.’

2

He immediately took charge of the government and relegated Viviani, whom he found ignorant and unreliable, to a minor role.

3

Rumours – true as it turned out – were coming in that the Russian government had ordered a partial mobilisation. Paléologue, perhaps hoping to present his own government with a fait accompli or for fear that it might try to deter Russia, had not bothered to warn Paris or the

France

ahead of time that Russia was mobilising. He also repeatedly assured Sazonov of the ‘complete readiness of France to fulfil her obligations as an ally in case of necessity’.

4

Later that day the German ambassador called on Viviani to warn him that Germany would take the first steps towards its own mobilisation unless France stopped its military preparations. That evening word came in from St Petersburg that Russia had refused German demands to stop its mobilisation. The French Cabinet, calm and serious according to an observer, met the next day and decided that it would not make any attempt to persuade Russia to comply with Germany. Messimy, the War Minister, took steps to move French forces

up to the frontier but these were to be held back ten kilometres from the border in order to avoid provoking any incidents with the Germans. The need to show that both to the French public and, crucially to Britain, which still had not declared itself, that France was not the aggressor remained uppermost in the minds of the French leadership.

5

Far to the east the pace towards war was accelerating. The military plans with their built-in bias towards the offensive now became an argument for mobilisation, to get the troops into place and be ready to launch an attack over the frontiers before the enemy was ready. Whatever reservations they had, the commanders and their general staffs spoke confidently of victory to the civilians, who found it increasingly difficult to resist the pressure. In Russia, with its great distances, Sukhomlinov and the military argued that a general mobilisation against both partners in the Dual Alliance was imperative: Austria-Hungary was already starting its mobilisation and Germany had taken preliminary steps such as calling back soldiers who were on leave. By 29 July his colleagues had managed to persuade Sazonov that it was dangerous to delay any longer. The Foreign Minister agreed to speak to Nicholas, who was unable to make up his mind.