The Well-Spoken Woman (15 page)

Read The Well-Spoken Woman Online

Authors: Christine K. Jahnke

A Good Story Isâ¦

- relevant to the audience

- purposeful

- simple but not simplistic

- based on policy and research

- arresting, unexpected, different, or new

Storytelling: Complexity Is Confusing

High-level managers and policy experts may resist storytelling, preferring to present facts and data. They may be overly concerned about peer judgment and fret that if they convey simple messages, their intellectual aptitude will be questioned. When speaking to insiders about a technical subject, jargon can help move the discussion along. When speaking to external audiences, the challenge is How do you reach them? Don't confuse savvy messaging with reaching out to the least common denominator. The real challenge is to figure out how to reach the

most

common denominator. This isn't about lowering standards; it is about setting high standards for effectiveness. Never assume what the audience knows and understands about the topic. The message will be lost in translation with the following mistakes.

Â

- Knee-jerk reaction:

With the denial “I am not a witch,” failed US Senate candidate Christine O'Donnell attempted to reassure voters that she was one of them. Instead, she came across as bizarrely defensive, especially to anyone who did not know she had formerly dabbled in witchcraft. - Laundry list:

Don't be the Al Gore of information overload with a litany of issues. If you talk about everything, your audience is likely to remember nothing. - Complexity:

Avoid diving into the weeds by belaboring the minutia and fine points of an argument. Senator John Kerry is infamous for explaining in detail why he voted for something after he voted against it. - Gobbledygook:

If you are a rocket scientist talking to another rocket scientist, then technical language is necessary and appropriate. But don't assume knowledge or awareness on the part of a lay audience. - Explainer:

Avoid a five-minute stream-of-consciousness answer starting with the history of the problem from decades ago when a sixty-second summary will suffice. - Johnny One-Note:

Don't be that person who talks about the same thing over and over again as if she has no idea that she is the person who is notorious for talking about the same thing over and over.

FIVE Cs OF MESSAGE DEVELOPMENT

The well-spoken woman's five Cs of message development provide a framework that ensures a message is not a big, muddled mess. The five Cs are fundamental principles that help you think strategically about what you must say to have an impact on a policy discussion or public debate. The principles will prepare you for a wide range of scenarios, including a live radio interview, a speech to five hundred, a contentious board meeting, a one-on-one with a VIP, questions from a newspaper reporter, the Q&A session at a conference, and a panel discussion talk. The principles of

clarity, connection, compelling, concise

, and

continual

ensure that preparation is geared to a specific audience with a specific purpose.

Principle 1. Clarity

We are a message-saturated culture with much of the information bombarding us from screensâhandheld ones; small ones in taxis and elevators; larger ones in lobbies, airports, and living rooms; and Jumbotrons® in auditoriums and sports complexes. Much of the information on those screens is advertising. It is estimated that the average person in the United States is hit with thousands of ads daily. It is nearly impossible to escape this dis-tracting and annoying overload. Principle number one is the need for clarity. Clarity is achieved by narrowing the agenda. With a limited number of messages, it is possible to cut through the clutter of overload.

Limit yourself to three or four main points about a topic: “three or four, no more.” A twelve-point agenda contributes to message static. Limiting the overall number of messages increases the likelihood the audience hears and retains what you want them to remember. Political candidates with narrowly defined agendas position themselves with the voters they need to win. When Senator Barack Obama sought the White House, he

used a three-point message that articulated who he was and what he stood for. Obama presented the rationale for his candidacy by exclaiming that Americans have the opportunity to choose hope over fear, unite rather than divide, and send a powerful message that change is coming.

The Obama message with the three values-based themes of change, hope, and unity succinctly positioned him as an outsider who would shake up Washington. The “Yes we can!” slogan was used to inspire voters to mobilize behind the vision. Successful candidates of all parties use a similar type of message construction.

Principle 2. Connection

A limited-message agenda requires a strong editing pen. You can't say everything, so you must decide what fits and what doesn't. Begin the process of prioritizing by asking a fundamental question: “Who is my audience? Whom do I need to talk to?” You are not talking to everyone. If you try to talk to everyone, you risk not talking to anyone. There are always three potential audiences. One group is the people who already agree with you and support you. Second are those people who, no matter what you say, will never agree. The third group is the people in the middle. They are referred to as the

persuadables

, or the ones who haven't yet made up their minds. They are open to hearing your side of the story, and you may be able to convince them to support your position or cause.

The Persuadables

To reach the people in the middle, you need to identify them demographically and geographically. Who are they, what do they do, and where do they come from? Establish the “who” first. Then you can move on to what will “move” them. What will get them to respond? What are their beliefs and values? What do they care about? What do they need? Draft your message

so that it will resonate with the target audience. Use language that will catch their attention and draw them in.

The Women's Collective is a nonprofit organization that provides care and support to women living with HIV/AIDS. The collective has a number of AIDS prevention programs aimed at helping women protect themselves, including one affectionately referred to as OPRAH. OPRAH is an easy-to-remember acronym for how to properly use condoms.

O

stands for open the condom carefully.

P

is for pinch the tip as it is put on.

R

means roll it all the way up. A: enjoy the action. And H: hold the condom snug until it is removed.

If the message isn't tailored to the audience, you run the risk of being misunderstood, maligned, and misquoted. For years, climate scientists have attempted to educate the public about the dangers of greenhouse gases and the impact of climate change. The effort has been stymied by the use of dense, incomprehensible language. Here is a typical example of a scientific explanation. Does the following definition of greenhouse gases illuminate or obfuscate?

These are gases which allow direct sunlight (relatively shortwave energy) to reach the Earth's surface unimpeded. As the shortwave energy (that in the visible and ultraviolet portion of the spectra) heats the surface, longer-wave (infrared) energy (heat) is reradiated to the atmosphere. Greenhouse gases absorb this energy, thereby allowing less heat to escape back to space, and “trapping” it in the lower atmosphere.

3

Unfortunately, many scientists struggle to translate their work because they are overly dependent on jargon. As a result, nonscientists have been confused about the dangers associated with greenhouse gases. Aren't greenhouses nice, warm places where plants grow? Thus, couldn't greenhouse gases be beneficial to the environment? Brenda Ekwurzel is a leading climate scientist who has been trying to clear up the confusion. When appearing on cable TV, Ekwurzel doesn't use the detailed charts and graphs she brings to professional conferences. Rather, she utilizes simple analogies, referring to climate scientists as essentially doctors who have been monitoring the earth's temperature and have diagnosed a fever.

The warming effect is caused by heat-trapping emissions from activities such as driving cars and burning coal in power plants. The more complex the point, the more essential it is to choose language that clarifies rather than obscures.

Principle 3. Compelling

Facts are not as effective as emotional appeals in motivating an audience. A climate-related scenario that is helping the public understand the impact of global warming is the melting of the polar ice cap. Photographs of polar bears on shrinking ice floes riveted audiences in a way the science never has. The pictures hit an emotional chord, raising awareness and concern about rising temperatures. According to psychologist and neuroscientist Drew Westen, facts and statistics alone are not persuasive and often raise more questions than they answer. Westen says: “There are a few things if you know about the brain, they change the way you thinkâ¦. If you understand we evolved the capacity to feel long before we evolved the capacity to think, instead of barraging people with facts you speak to people's core values and concerns.”

4

Leaders of the tea party movement seemingly embraced Westen's advice with a message loaded with rhetoric that nearly derailed the passage of healthcare reform. A well-orchestrated campaign led by talk radio host Rush Limbaugh tapped into the anxiety felt by people who didn't know how reform would affect the quality and cost of care. At town hall meetings, tea party activists deployed a disciplined message to argue against proposals put forth by the White House and congressional leaders. The theme with the greatest resonance was “death panels.” The deathpanel claim lacked veracity but nonetheless was successful in causing fear, particularly among senior citizens.

In a controversial debate, the side that makes the stronger emotional appeal often gains greater, more broad-based support. Unfortunately, some advocates have been willing to throw facts and reasoning out the window in order to win policy debates. In the long run, win-at-all-costs rhetoric can backfire, and it is a disservice that undermines the efforts of wellintentioned policy makers. The key is to make an emotional appeal while

remaining intellectually honest. A message needs to feel like there is a person behind it with a heart and a brain. Facts lend legitimacy to an argument but are open to interpretation. Emotions amplify an issue, making it more comprehensible. Balance hard data with a passionate appeal.

Principle 4. Concise

In E. B. White's classic tale

Charlotte's Web

, a spider named Charlotte spins a simple message to save her friend Wilbur the pig from the butcher's knife. In the ceiling beams above Wilbur's pen, Charlotte spun a web that read: “Some Pig.” The succinct message quickly convinced Wilbur's farm family that he was no ordinary barnyard animal and should be spared. Charlotte's web mastery demonstrates that much can be said with just a few wellchosen words.

Communication today demands brevity. Audience attention spans continue to shrink. Twitter® has a 140-character limit. Network TV reporters want sound-bite answers in roughly ten to twenty seconds. This is as much about self-restraint as it is about finding the right words to fit a limited space. Mark Twain quipped that he would have written a shorter letter if he had more time. Less is always more, but less can take more time. Simple and short doesn't mean simplistic.

Principle 5. Continual

Creating an echo chamber with a message that reverberates is another way to break through clutter. It takes many repetitions to hit a nerve with audiences reeling from information overload. Listeners need to hear, see, or read a message between seven and twelve times before they get it. Advertisers strive to create a “wear in” effect so that consumers experience an ad enough times that it prompts a response. That's why we keep hearing about how the Energizer bunny's battery is going and going and going.

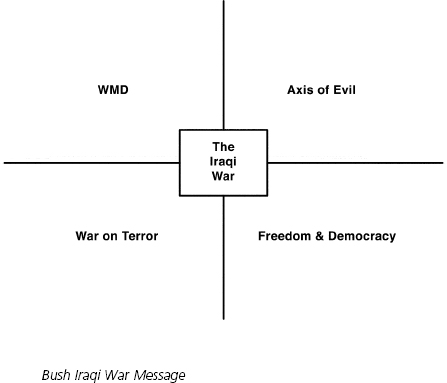

In the 2002 State of the Union address, President George W. Bush used the occasion to present his rationale for the war with Iraq. The address was the first time the president had spoken directly to the American public about the need to send US troops into war overseas. The message

was intended to resonate with a nation that was still reeling from the unexpected 9/11 attack.

Bush said the war was necessary because of the following:

Â

- We need to take out Saddam Hussein, a nasty dictator who used “weapons of mass destruction” against his own people.

- The Cold War is over, but the world is still a dangerous place. There exists an “axis of evil,” namely, Iraq, Iran, and North Korea.

- We need to fight the “war on terror,” and it is better to fight it over there than to have to fight it here at home.

- It is up to America to bring “freedom and democracy to the Iraqi people,” and our troops will be welcomed on the streets of Baghdad as liberators.