The Witling (21 page)

The elderly Guildsman smiled. “More than that, dear My Lord. I intend to cooperate with them.”

“What!”

“That’s right,” Mileru said. On the map between them he pointed at Draere’s island, three-quarters of the way around the equator from County Tsarang. “At their convenience, I will teleport them here.”

“Why, blood and bile, Lan. You’re as crazy as they are! That’s more than one hundred and twenty-five leagues. A four-league jump is enough to shatter the hull of the toughest road boat. We can’t even reng message balls more than twenty leagues without risking their contents.” He all but bounced off the bench in his agitation.

Lan Mileru seemed to be enjoying the other’s consternation. “Nevertheless, Dzeru, I have been convinced they should be allowed to try.” He held out Prou’s letter.

But Dzeda waved it aside. “If you three are so eager to smear yourselves across that speck of mud out in the ocean,” he said to Ajão, “why did you bother coming to County Tsarang? Why not have some Guildsman reng you there direct from the Summerpalace? The palace is closer to the island than Tsarang. And there are places in the Snowkingdom that are still closer: I’ll bet if you made the jump from Ga‘arvi, you’d crash into your destination ‘gently’ enough to leave recognizable corpses.”

Ajão smiled at the other’s sarcasm. “There is a reason for coming to your county, My Lord. If we make the jump from here, we will be thrown upward from the ground at our destination.” The problem was not especially difficult to visualize. Imagine the planet spinning on its axis, a vast, spherical merry-go-round in space. The Summerpalace was just ninety degrees east of Draere’s island; if they jumped from the palace they’d be smashed into the ground when they emerged at the telemetry station. Ga‘arvi was a better prospect (except that it was a Snowfolk town). Renging to the telemetry station from there would be like hopping from the center of a merry-go-round straight out to the edge: they would arrive moving due west—at nearly the speed of sound. Yoninne had dismissed Ga’arvi with the comment, “Who wants to make a belly landing at mach one?”

But as you followed the continent from Ga’arvi to the isthmus of Tsarang, the situation improved. If they jumped to Draere’s island from Tsarangalang, they would arrive moving better than a kilometer per second—but that velocity would be directed upward at almost 23 degrees. The only better jumping-off point in either hemisphere was the east coast of the isthmus, but that was under Desertfolk control, and besides, there was no Guildsman there.

“I realize,” Bjault continued, “that our boat might still crash into something—a steep hillside or cliff face, for instance—but this is about the best we can do, given the arrangement of Giri’s continents.”

Dzeda shook his head despairingly. “No. You’ll die in any case. Don’t you realize that when air moves fast enough, it might as well be solid rock? I’ve seen men and war boats struck by air renged from sixty leagues: the men spattered, and the boats were turned to kindling. Your boat may be strong, but nothing can resist forces like that.”

Ajão started to disagree, but the count raised his hand. “Let me finish. I know Shozheru has put you under what amounts to a suspended death sentence. Either you go through with this plan or he executes the three of you. But you’re in County Tsarang now. We were an independent state long before there even was a Summerkingdom. Back at the palace they may call me count and vassal—but out here that’s not quite the way things are: I am willing to grant you a secret asylum, to report to the Summerkingdom that you went through with your plan. Frankly, I think this is what your father was aiming at when he agreed to this scheme, Pelio. His advisers may be cold men, but he is not.

“How about it? Will you stay?”

Ajão was silent. For Yoninne and himself there was no choice. Unless they could get to the telemetry station and call in a rescue ship from Novamerika, they would die—and soon. Already he was beginning to feel the same pain and weakness he had on the trip to Grechper.

Pelio

did

have a choice. Dzeru Dzeda’s offer finally took him off the deadly hook that Ajão and Prou and Yoninne had forced him onto. Perhaps their machinations wouldn’t ruin the boy’s life, after all.

But the young prince looked from Bjault to Dzeda, and then slowly shook his head. “I want to be with … I mean, I want to go with Adgao and Ionina.”

The count saw the refusal in Ajão’s face, too. He pursed his lips, and for a moment seemed lost in minute inspection of the floor between his feet. There was a wan smile on his face as he looked back at Ajão. “Well, I tried, good witling. You may never know how scared I am: scared of what might happen if you fall into unfriendly hands; scared of what your people may do to us if you bring them back here. My race has always depended on its natural Talent—while yours apparently has none: you’ve had to substitute ingenuity and invention for Talent. Somehow, I suspect that’s taken your people much, much further than mine have come.”

Something turned to ice in Bjault’s spine: this petty nobleman could destroy their last hope for rescue if he chose.

But Dzeda bounced to his feet, and some of his cheerful nature returned. “But at the same time, I’m overburdened with soft-heartedness. And curiosity. If your insane scheme works, the future could be an interesting place, indeed.

“Give them whatever they need, Lan,” he said over his shoulder, as he walked to the transit pool. “I’ll be out on the East Line the next few hours, keeping watch on our unfriendly neighbors.”

Through the wide windows of the count’s manse, Ajão could see bands of orange and green the setting sun had spread above the ocean to the west, while the mountains in the east were barely darker than the sky there. The warm bluish twilight that filled the gardens about the manse was infinitely cheerful compared to the stark light and dark they had traveled through at the poles.

Bjault shook his head, trying to concentrate on the fiberene chute that was spread around him. The temptation to quit, to get some sleep, was overpowering. But he knew that part of his fatigue was not natural. Every time he smiled into a mirror he saw the line of blue along his gums. The pain in his gut was getting steadily worse, much as it had on the trip to Grechper. Only this time he might not recover from the attack. If they didn’t make the jump soon, there was a good chance he would be too sick to guide the skiff to a landing once they reached Draere’s island.

Dzeda’s men had moved the skiff into the manse’s meeting hall. It sat on the marble floor, and all around it lay the parachute’s olive fabric. Across the room, Pelio and the others worked to remove every fleck of dirt from the slick material.

But folding the parachute was something which only he, Ajão Bjault, could do. The packing pattern was intricate, and each of the canopy’s movable flaps had to be specially accounted for; a single mistake could be fatal. As the minutes passed, the ache in his tired arms became a pulsing fire. Soon he needed Pelio’s help to compact the mass he had folded.

Early in the afternoon, Ajão had briefly considered a plan that didn’t require the chute to be repacked: if they could get a Tsarangi volunteer, perhaps they could

fly

the skiff across the ocean, the same way Bre’en had flown them over the mountains. But Draere’s island was nearly twenty thousand kilometers away, and Lan Mileru pointed out that even a two- or three-man

team

of teleports couldn’t keep the skiff airborne for the hundreds of hours it would take to fly that distance.

So they must stick to the original scheme: Lan would teleport them across the ocean in a single jump; they’d slam up into the air over Draere’s island at better than a kilometer per second, fast enough to rip even a fiberene chute to shreds. Only when their speed fell well below mach one could they pop the chute and sink “gently” to a landing.

Suddenly Bjault stopped work, stared blankly at the pile before him. His mind had wandered; what was next? Back in the Summerpalace, he made Yoninne show him every step of the folding process. She had considered the demand a waste of time, but now the memory of what he had seen there was all he had to guide him.

Yoninne, girl, what I wouldn’t give to have you here swearing at me

. Only now did he realize what an effective team they had made. Again and again he’d come up with a good idea, and Yoninne would somehow put together all the details to make it work.

The last colors of sunset had faded when Pelio and Dzeda’s men squeezed the chute into its retaining straps. The fabric no longer looked fragile and gauzy. Ajao’s careful work had transformed it into a thick, dark slab that massed nearly as much as an equivalent volume of rock.

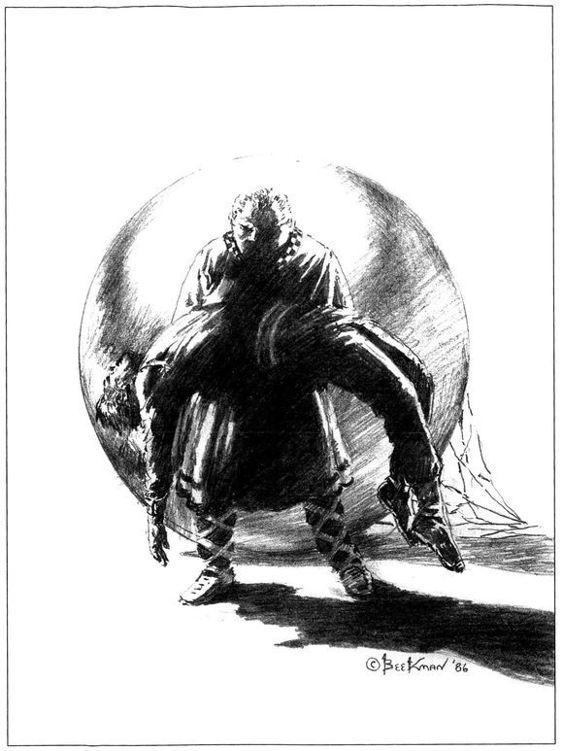

While Ajão and Lan watched, the younger men lifted the pack and set it in the rectangular slot at the top of the skiff. Then Bjault closed the cowling over the chute and crawled through the passenger hatch into the vehicle. He moved slowly now, his body bent. The pain in his middle made it all but impossible to think. For a moment he lay quivering in the darkness—then Pelio called to him, and someone held a torch in front of the hatchway. Ajão gagged on the oily smoke, and forced himself upright. “I’m all right,” he said to the men outside. Back to work: he connected the chute release, then briefly checked the cords holding the lead ballast in place.

Finished

. He crawled out of the skiff, and stood swaying on the marble floor. “Lan, we’re ready. You can jump us in four hours.” That would be the middle of the night here—but morning at Draere’s island.

Even by the flickering torchlight, Ajão could see real concern on the old Guildsman’s face. “Perhaps you should wait. Just a day or two.”

“No!” Ajão opened his mouth, tried to put his reasons into words, but all he knew was the pain in his middle. The floor swung up toward his face, and everything turned black. He didn’t feel Pelio’s arms break his fall.

As it happened, Bjault’s wishes prevailed, even though he was not awake to argue for them: the Snowmen attacked shortly after midnight.

A

jão struggled to wakefulness, trying ineffectually to shake off the hands on his shoulders. From all around him came the crash of thunder—and something that sounded terribly like small-arms fire. He forced his eyes open and looked blearily at the shadowed face above him.

The count’s voice was barely intelligible over the noise outside: “Blood and bile, good witling, I was beginning to think nothing would stir you—Lan, he’s awake—” He shouted the words over his shoulder, then turned back to the Novamerikan. “We’ve got to get out of here, and fast. Can you walk?”

Bjault came cautiously to his feet, but felt little of the earlier pain. Only now did he see the extent of the disaster that was falling about them. Across the room, Pelio and Mileru were helping county troops slip Yoninne onto a stretcher. Less than three meters from her feet, the thick wood wall lay in shattered ruin. From the moonlit landscape beyond, the sounds of destruction continued. “What’s happening?” he shouted to Dzeda, but a thunderclap blotted out his words. He let the count push him into the room’s transit pool, along with the other witlings and Samadhom.

A second later they emerged in the meeting hall of the county manse. This was several kilometers from the bedrooms, and the sounds of combat were muted here. A moon shone through the room’s crystal windows; the soldiers standing around the water looked pale and worried. Ajão repeated his question, and this time Dzeda replied, “—tried to surprise us. There are a few Sandfolk who have made the pilgrimage to the Tsarangalang transit lake. They are being used to reng the Snowman army into the city. I’ll bet Tru’ud thought if he hit us hard enough he could capture or kill you two before we could react—and he was almost right.”

A nearby soldier interrupted. “The messengers say they’ve got roadblocks on nearly every lake within three leagues, M’Lord.”

Dzeda frowned, and said to Lan Mileru, “What do you seng?”

“I think he’s right, Dzeru. The lakes are quite turbulent.”

“Very well. We’ll pull back. If the Snowfolk keep this up, I’ll be asking for Guild assistance.”

“You’ll have it,” Lan replied.

The count gave instructions to a squad of messengers, then turned to Ajão and Pelio. “By the monsters in the sea, Tru’ud is risking everything to get his hands on you. And as long as you’re in the county he stands a fair chance of succeeding. Adgao … are you up to going through with your plan right now?”

Bjault looked down at Yoninne’s still form on the litter. Pelio said, “She’s no worse than before, Adgao.” Outside, the crack and rip of war sounded louder. He looked at the count and nodded. The pain in his gut had diminished—though not as completely as at Grechper. This was the best chance they would ever have.

“Good. Lan?”

“I’m ready, Dzeru.” They walked across the hall to the ablation skiff. The Guildsman had the soldiers turn the skiff to the compromise attitude he and Ajão had decided on: something Mileru could manage, that would leave the skiff’s center of mass roughly in line with their direction of flight when they emerged at Draere’s island; otherwise, the hypersonic entry would put them in a spin that would rip the interior ballast from its moorings and splatter them to pulp. But the skiff was so small and dense that the troopers had a hard time getting leverage on it. And the further it was tipped to the side, the more dangerous its tendency to roll.