There Was a Little Girl: The Real Story of My Mother and Me (8 page)

Read There Was a Little Girl: The Real Story of My Mother and Me Online

Authors: Brooke Shields

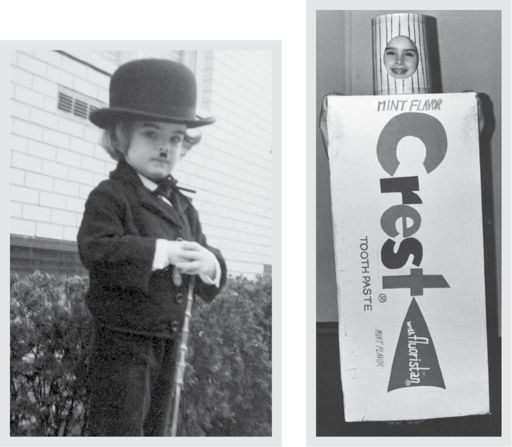

Mom put so much time into my costumes I began to expect to win the contest at the gymnastics space, Sokol Hall, where we’d attend their annual party. Because we lived in an apartment building, trick-or-treating was easy and I could go alone with a friend. I’d invite

a school buddy and we’d begin on the penthouse floor and work our way down. It took hours, and our pumpkin-head buckets would be overflowing by the time we got to the lobby apartments. This was the height of the razor-blade-in-the-apple panic, and I was never allowed to eat any of my loot until after Mom had done a thorough check. It was always fine because we knew every inhabitant in the building. I never actually ate all the candy I got. It usually got stale before I finished even half the bucket.

Another story I love was about my doll, Blabby. Blabby was a doll similar to the amazing Baby Tender Love dolls of the seventies that I adored, but she was more unique. She used to make a sound like a baby cooing when you squeezed her rubber stomach. I took her into the bath with me so many times, however, that the coo soon turned into a bark. Later, with my kid scissors, I cut off almost all her hair. She looked rather punk and ahead of her time, but soon, because of the baths and the brushing, it all fell out.

Blabby went everywhere with me. When we traveled by plane, Mom would strap her in with me in the seat. The seat belt went around us both and was fastened only when Blabby gave a “nod” that it was tight.

When I was around six years old, Mom and I had a layover in some city on our way back to New York. I had left Blabby in the terminal while waiting for our connection and playing some Pac-Man–type game. We hadn’t noticed until Mom was strapping me into my seat and realized Blabby wasn’t on my lap. The plane had begun its taxi on the runway when my mother suddenly and frantically called for the flight attendant. She told me not to say a word and then looked straight into the stewardess’s eyes and calmly and emotionally, but deadly seriously, said, “We must get off this plane! It is a matter of life and death.”

This was way before 9/11, and security was much more lenient. The flight attendant must have been alarmed enough, though, so she went to the cockpit and they stopped the taxi and returned to the gate to let both of us off. Mom and I deplaned without saying another word and I went directly to the game I had played before boarding the plane. Blabby was not there, so we tried lost and found. We reported Blabby’s physical profile and had been waiting for over an hour when, from a distance, we saw a male airline official walking toward us, holding something behind his back. He was hiding my doll with an air of embarrassment and was, no doubt, relieved to returned her to me. Well, he could not have been more relieved than I was. I knew my mom would fix the situation.

I still have Blabby. But because she is bald and now has a large split down the middle of her head, my girls say she is “creepy.” I don’t agree. I have never before, nor since, seen a doll similar to her. Mom had given her to me, and after she died I put her necklace on Blabby. Creepy or not, she still sits in my room and reminds me of the time my mother stopped a 747 on a runway to retrieve my baby doll.

Mom probably loved the fact that she could wield that type of power. She always said that as long as you remain firm in your opinions and in their delivery—even if you’re not telling the entire truth or you’re not completely clear—you’d be surprised at what you can achieve.

• • •

Mom has been an unconventional person her whole life, and she wasn’t about to change just because she had become a mother. She continued to take me to bars even as I got older. I remember when she taught me to shoot pool from behind my back. I couldn’t have been older than eight and I learned fast. When I’d excitedly called my father and said, “Dad! I just learned how to shoot pool from behind my back,” I remember him saying: “Where are you?”

“At a bar,” I said.

“Jesus Christ.”

I’m sure Dad wasn’t thrilled with any of this, but I was seemingly safe and having fun, and my mother seemed in control. The argument was tough to have.

The most useful bar talent I acquired—before learning how to tie a knot in a cherry stem with my tongue—involved holding up twelve sugar cubes stacked in between my thumb and pinky finger. It was this skill that I would use as the beginning of a conversation with the one and only Jackie Onassis.

Mom and I were at her long-standing favorite bar, P. J. Clarke’s, when Mom spotted Jackie and Aristotle sitting at the tiny window seat in the empty middle section of the restaurant. It was their table! Mom said, “Brookie, that’s the mother of the boy you are going to grow up and marry.” Without waiting for permission, I leapt up and went over to the table to politely introduce myself.

I evidently went right up, said, “Hi, when I grow up, I am going to marry your son.” Jackie said, “Oooh . . . ,” as if the thought of her little

boy growing up was too much to think of. I then showed her how to hold as many sugar cubes as she could between her two fingers. I simply showed her how to do this trick and then returned to my table. My mom claimed she was embarrassed, but it made for a great story and she loved to tell it.

Mom’s version of discipline was unconventional. She was creative with punishments. I once begged her to let me have Devil Dogs for dinner. I cried, pleaded, and threw a tantrum, wanting this cakey, creamy, artificially made dessert snack for my meal. Mom finally conceded but said that if I really wanted Devil Dogs for dinner, I’d have to eat twelve of them. I thought I had hit the junk food jackpot until the third one brushed the roof of my mouth. I started to feel sick and ended up throwing up all over the bathroom. Mom simply asked if I ever wanted Devil Dogs for dinner again. I don’t believe I have ever had one since. (Two major cakey junk foods crossed off my list!)

She wasn’t afraid to embarrass herself, if necessary, to make a point. She once took my cousin Johnny to see

Godzilla

(which he called

Godzillabones

) and he threw a tantrum when leaving the theater. She immediately got down on the floor and threw her own tantrum, shocking Johnny and showing, once again, how creative—nd effective—her discipline could be.

• • •

Some of the stories Mom thought were funny could also be scary. She was great at imitations, and most of them I loved because they made me laugh. But the one I did not enjoy at all was her imitation of the Witch in

Snow White

. In the animated movie the witch had this horrible and terrifying cackle that my mom could copy flawlessly. She would do it randomly and it unsettled me horribly. I’d beg her to stop; she’d continue the imitation for longer than I would have liked. I loved her ability to mimic and I consider my talent in this area a gift

from her, but the minute Mom started with the voice, I’d start chanting, “You’re my mother, you’re my mother!” She simply wanted to do what she wanted to do and loved the attention. I don’t think Mom ever knew I was actually, honestly scared. She would later tell this story and beam with pride at the fact that I kept repeating that she was my mother.

During these years my modeling career really began to take off. Mom was my manager, but she was hardly the typical “stage mother” one would have expected. She’d ask if I wanted to go in for a job and then simply let me do my thing. She never grilled me on how it went inside the rooms and instead waited for me to volunteer information. I am sure she would have loved getting feedback, but I don’t remember her ever pressing me. When I did not get the job, she would just brush it off and we’d discuss what we should do with that free time. There were many times we’d hear parents through the elevator door screaming at their kids or even slapping them. We often heard the sound of crying getting fainter as the elevator descended to the first floor. I never understood why moms promised their kids things like bicycles if the kids agreed to go in on a “go see.”

If the kid didn’t want to model, I thought he shouldn’t have to. My mother never bribed me or forced me to audition or work on things or on days I didn’t feel like it. Granted, I was quite young and hardly ever stood up to my mom, but I don’t recollect feeling pressured, like I was being forced to do something I didn’t want to do. Mom made me feel that it was all my choice. She’d say I could stop anytime I wanted to. I, of course, wanted nothing more than to please her, so I rarely refused to do anything. On any particular day, if I ever expressed not wanting to go in for a job, Mom would unplug the phone or we would escape the house and go to Central Park.

This infuriated clients and agencies, but it ironically made me more sought after.

No

is a powerful word.

Strangely enough, I got only a few jobs in commercials. I was cast

in a Johnson and Johnson Band-Aid ad and a Holly Hobbie doll commercial, but it quickly seemed that my looks were not considered all-American enough, and I was often turned down and labeled “too European.” Whenever I did get a job, I knew I’d have fun no matter what, and my mom would feel happy. It was a win-win situation.

I learned early on that the sweeter I was to the adults, the nicer they treated me. It was all just for fun during those years, or at least it seemed that way to me.

I stayed at my grade school in Manhattan while working and rarely missed a day to model. On some of the bigger trips, I might miss a Friday. Even as I got older, Mom maintained this rule. If the agency phoned to say I had a shoot for 10:00

A.M.

on a Thursday, Mom would respond by saying that was great and we would see them all at 3:00. If they pushed, she’d claim that if they didn’t want me, it was fine to choose another child, but I would not be available until after school let out at 2:40. Basically, while other kids were involved in after-school sports or playdates, I was shooting for various catalogues. I can’t say I minded not playing sports or being forced to spend any time separated from my mother.

I have a lot of great memories from these early years. I was once cast as Jean Shrimpton’s daughter in an ad. Mom always said that I looked more like her than any other model or actress. Mom thought she was beautiful and had a face with perfect symmetry.

Over the next few years I modeled in ads and catalogues for Macy’s, Sears and Roebuck, Bloomingdale’s, Alexander’s, McCall’s, and Butterick. Whenever I had a “go see,” Mom remained in the background. On set, Mom was not one of the moms who made her presence imposing. She never hovered over the creative team or offered unsolicited direction to me. She saw everything and had her opinions about everybody, but during these days, she was more subtle and did not share her judgments with me.

Our life was active and fun. We basically each had a full-blown career. I modeled and Mom managed.

By the time I was ten, it became obvious that I was in need of larger and more credible representation. Mom looked around at the various available children’s agencies for models and was evidently dissatisfied with what she found. Even then, she had high aspirations and was not content settling for anything she deemed commonplace or plebeian.

Because she frequented many photographers’ studios and artists’ lofts socially and had friends who worked at cosmetic and hair care–oriented companies, she knew the best in the business. The models she loved all seemed to be represented by the Ford Modeling Agency and she knew the top ad agencies looked to them for their talent. Ford was an agency with such prestige and power that Mom decided it was the only suitable place for her baby girl.

In 1974, Ford Models did not have a children’s department and had no plans of incorporating one into their already thriving business. But we had an in. Eileen and Jerry Ford, who had started Ford Models, knew my father from various social circles and from supplying models for Revlon ads, and my dad was now working for Revlon as a sales executive.

I remember that my mother had met Eileen and Jerry many times. They had all remained friendly, so Mom decided to approach Eileen personally. She loved to tell the story about how one day she opened the door and marched up the three flights to Eileen Ford’s spacious and bright office. Mom said she stood in front of Eileen’s desk with her hands on her hips and explained to Eileen, “This agency doesn’t have a children’s division, and it should. Brooke will be your first child model.”