They Marched Into Sunlight (14 page)

Read They Marched Into Sunlight Online

Authors: David Maraniss

Tags: #General, #Vietnam War; 1961-1975, #History, #20th Century, #United States, #Vietnam War, #Military, #Vietnamese Conflict; 1961-1975, #Protest Movements, #Vietnamese Conflict; 1961-1975 - Protest Movements - United States, #United States - Politics and Government - 1963-1969, #Southeast Asia, #Vietnamese Conflict; 1961-1975 - United States, #Asia

W

HEN

N

ED

B

RANDT

and two associates arrived at the Pentagon at ten on Monday morning, March 13, they were armed with a memo listing five actions the Department of Defense could take to help Dow. First, they wanted a statement from Defense explaining “the necessity for napalm, policies governing its use and its effect in terms of war effort.” Second, they would request a letter from Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara, on his stationery, “stressing the need for napalm to protect American soldiers” and praising Dow’s contribution in that regard. Next, they sought another letter from General Westmoreland “emphasizing the lives of American soldiers which have been saved because of napalm.” Fourth, they would ask for a “visit by medal of honor winner or other battle-scarred veteran to Midland, Freeport, Torrance for personal appearances in plants. He can give first-hand reports of napalm’s tactical benefits.” And finally, they would ask whether they could “hire a free lance writer in Viet Nam to write battle stories where napalm played a key role in saving our boys on the front line.”

Brandt assumed that his delegation might get no further than the press office or be shuffled from one low-ranking paper pusher to another. Instead they were ushered into a large meeting room where they found themselves being faced down by a panel of six colonels arrayed on the other side of a long table. The visitors were directed to sit submissively in front of the table. It was “kind of like a court martial setup,” Brandt thought, and his guys were in the chairs “that normally would have been for the accused.” If it was not a court martial, neither was it a freewheeling give-and-take about the relationship between the corporation and the military. For three quarters of an hour the colonels fired questions at the public relations men while revealing nothing about themselves. Brandt went into the meeting never having heard the Pentagon’s position on the anti-Dow protests and went out no further informed.

As he was leaving, Brandt brought out a copy of a letter he had drafted and handed it to a Pentagon official. It was a suggested version of the letter Secretary McNamara could send to Herbert Dow Doan. (In a late revision he had even included a mention of Dr. Rusk’s napalm report from Saigon.)

“Dear Mr. Doan,” the draft began, “We have followed with considerable interest and concern the newspaper accounts of the demonstrations and protests that have for some time been directed against your company as a major supplier of napalm for the armed forces. It is, as you know, highly unusual for such protests to be directed against the manufacturer, rather than the military user, of a weapon, even one as emotion-laden as napalm B. In what must surely be rather trying circumstances, the conduct of your company has been exemplary…”

Chapter 6

Madison, Wisconsin

T

HE 1967 FALL TERM

was not yet a month old when a crowd of rambunctious students at the University of Wisconsin spilled from the southeast dorms of Ogg and Sellery looking for action. It was midweek, a Wednesday, ten

P.M.,

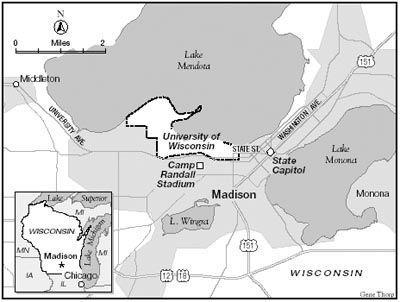

and the air was rapturously warm and alluring, a welcome break from the dispiriting blanket of gray that had settled over Madison so prematurely that year, wiping out the last month of summer and bringing intimations of the long frozen winter to come. Feeling free and easy in the balmy night, the young men marched north toward Lake Mendota, skirting the Library Mall and the Old Red Gym, then turned right and headed up the curve of Langdon Street, picking up more recruits from fraternity houses there until they were nearly a thousand strong. The first stop was Langdon Hall, at the time still known as a “girls” dormitory. “We want silk! We want pants! We want sex!” came shouts from the street, and out flew some panties but more rolls of toilet paper.

The crowd undulated up and down Langdon and then oozed across to State Street, passing more targets along the way. A small squad of Madison cops, some in uniform, others in plainclothes, monitored the students until they reached the sidewalk on the far side of Park Street at the bottom of State. That marked the official boundary of the university, and according to Inspector Herman Thomas, city officers would not enter the campus proper unless UW administrators formally requested their presence. Up the long rise of Bascom Hill went the student battalion, past the statue of seated Abe Lincoln and around the side of Bascom Hall onto Observatory Drive, dipping down the back slope past the Commerce and Social Science buildings, and then up again and along the ridge toward Elizabeth Waters, another dormitory for women. A score of young men were seen entering the dorm uninvited, but they scattered when spotted by a housemother, and from there the crowd dissolved in the darkness. There was minor retaliation the next night. A few hundred freshman women, mostly from Chadbourne Hall, rallied on the steps of the Memorial Union, then marched to Ogg, where they were greeted by the swoosh and splash of shaving cream and water balloons.

The culture was changing in 1967, certainly, and Madison was said to be in the vanguard, but the counterculture stereotypes later imposed on the university, as on the entire decade, fail to capture the more variegated reality of that time and place. A nocturnal panty raid was still part of the campus scene. There was not yet a glimmer of the notion that young men and women would be allowed to live in the same dormitory tower, let alone on the same floor. Visitation hours for men in the women’s dorms were limited to 2:00 to 9:30

P.M.

on Sundays. Three freshmen had been disciplined already that fall for breaking the women’s curfew on a Saturday night. They had gone to Milwaukee to participate in a civil rights march, after which one straggled back to her dorm a shade past 1:30 Sunday morning and the others were even later. As punishment they faced a week to three weeks of restricted hours. Along Langdon Street the Greek subculture had not yet slipped into disfavor. The talk that fall was of a meningitis scare that began with a “kissing party” involving fraternities and sororities. When one young smoocher ended up at University Hospital with a mild case of the disease, panic spread and five hundred students who might have had contact with him reported to the health clinic for preventive sulfa pills.

Five years removed from past Rose Bowl glory, the Badger football team was dreadful, on its way to a winless season that inspired one loud and repetitive refrain from the student sections—“ooooohhhhhh shit!” But on the sidelines that fall, making their inaugural appearance, were sixteen pompom girls dancing in red and white miniskirts. A hundred coeds had tried out.

The crosscurrents of the times were readily evident. On the first day of fall classes, a mime troupe affiliated with

Connections,

a radical alternative newspaper, put on an early version of performance art, or guerrilla theater. Posturing as rightwing storm troopers, they barged into lecture halls, hauled out student activist compatriots, and dragged them to mock executions at the top of Bascom Hill. Two nights before the puerile panty raid, Allard Lowenstein, director of the national “Dump Johnson” movement, appeared on campus and told a gathering of students that they could be the key to his entire scenario. If they produced a strong vote against the president in the 1968 Wisconsin primary, he predicted, “there would be many political implications.”

McCall’s

magazine had labeled Wisconsin the number two drinking school in the nation, but that was stale news to the student newspaper, the

Daily Cardinal,

which was running a series on the mind-bending effects of LSD and other hallucinogens. The albums of the Jefferson Airplane, Buffalo Springfield, and Big Brother and the Holding Company were being sold at Discount Records and Victor Music on State Street, and the Beatles had made their cultural turn that summer with the release of

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band

—“She’s leaving home, bye, bye”—but WISM in Madison and WLS in Chicago were still playing a Top 40 list that included Tommy James and the Shondells, Bobby Vinton, Bobbie Gentry, Herb Alpert, and Nancy Sinatra.

Meetings of the student senate were sparsely attended at the same time that a faculty committee earnestly considered the issue of “student power,” something that student testifiers knew they lacked but could not necessarily define. The Anti-Military Ball, a counterculture tradition at Wisconsin, was held on the eve of the ROTC party and drew more students. They danced under the slogan “Anti-militarists have balls.” The Madison chapter of Students for a Democratic Society usually drew more people than the student senate and had its own newsletter, but the largest campus rally earlier that year was one in which moderate students gathered under the banner “We Want No Berkeley Here”—and the largest club on campus was not SDS or Young Democrats, but Young Republicans.

Then there was the visage of Robert Cohen, a teaching assistant in philosophy who prided himself on looking like a beatnik. While Cohen was serving time behind bars at the Dane County jail on a disorderly conduct conviction stemming from an earlier protest, his scraggly black hair and beard had been buzz cut into oblivion by local barber Sam Fidele, who had volunteered his services for the occasion. Cohen complained that the sheriff had “this sexual thing” about beards and that his jailers failed “to comprehend the historical alternatives to their present non-qualitative existence.” The haircut, he said, stripped him of his “philosopher’s image.” The sheriff said it was for “health reasons.”

All part of the atmosphere of Madison, Wisconsin, 142 miles northwest of Chicago, 77 miles west of Milwaukee, surrounded by the dairy farms of Dane County on some of the richest black soil in America, connected to the world and yet a place apart. Madison, nourished by four elements: the politics of its state capitol, the intellect of its university, the calm beauty of its lakes, and the grace of its American elm trees. All seemed permanent and immutable, but they were not, not even the trees, sixty thousand elms that formed exultant archways of green over the old city streets. It turned out that they were diseased and dying, more year by year, 937 that year, up from 763 the year before, on toward an awful slaughter that would wickedly mimic the worst devastation of north country timber barons by cutting hideous bare swaths through neighborhoods that once ached with leaves. The old elms were being killed by a fungus that clogged their circulatory systems, cutting off water and sugar. It was called Dutch elm disease, and arborists said it spread from the east.

There were 5,385 freshmen at Wisconsin that fall out of a total enrollment of 33,000, and they represented—geographically, though not racially—by far the most diverse population of any public school in the Big Ten. More than 28 percent were from out of state, including 283 first-year students from New York alone. The Wisconsin Idea, conceived by leaders of the Progressive movement early in the twentieth century, was to use the UW as a “laboratory for democracy,” a resource of science, agriculture, social policy, and creativity available to the government as well as to every citizen in the state. The philosophy of the Wisconsin Idea was to reach out, rather than withdraw inward, and an unspoken but respected aspect of that was to reach beyond the state’s borders to reinvigorate the social and intellectual environment, a process that had been encouraged since Charles R. Van Hise (felicitously, a rock scientist from Rock County) presided over the campus from 1903 to 1918.

A long-standing practice within that tradition was for Wisconsin to accept significant numbers of Jewish students, mostly from Chicago, Saint Louis, and the East Coast states of New York and New Jersey. For decades the student body was more diverse than the faculty, which had few Jewish professors until the early 1960s, by which time there were third-generation Jewish students following the same path their parents and grandparents had taken to the school in Madison that had welcomed them when much of the Ivy League had not. Michael Oberdorfer of Bethesda, Maryland, a graduate student in zoology and photo editor at the underground paper

Connections,

was part of that lineage. Oberdorfer’s father, mother, and stepfather had all gone to Wisconsin in the late thirties. Among the family keepsakes was a letter the father had written as a young man explaining that he was heading west to Wisconsin because he had been made to feel unwelcome at Harvard.

But here was another crosscurrent: the steady infusion of students from other places, combined with the politics of the moment, had provoked a provincial response. In the aftermath of a series of antiwar demonstrations on campus, including a long but peaceful sit-in at the administration building in the spring of 1966 and a briefer occupation of the chancellor’s office the following spring—both led for the most part by out-of-state students—angry alumni and state legislators pushed for a tightening of nonresident admissions. The university responded with a plan to reduce the out-of-state maximum to one-quarter of the undergraduate enrollment within three years. The 1967 freshman class marked the beginning of that process; only a year earlier, a record 38.6 percent of the new students had come from outside Wisconsin.