Thirteen Chairs (4 page)

Authors: Dave Shelton

But then it isn’t silent any more. It’s only a little

noise, but it’s just enough that he can’t ignore it. It’s coming from downstairs, a little high

plink

. Just a single note played on the piano, but it seems to ring on and on. Then, when it seems to be fading away to nothing, it sounds again.

Now, that piano hasn’t been played in years. It was Helena’s late husband’s, but he passed away very many years ago, terribly young. (‘Gone to a better place,’ said the vicar at the time, and you could tell he meant it more than usual, like.) But now there’s this high, soft note coming from it, again and again. Roland can barely make it out, it’s so quiet to begin with, and coming from down the stairs and round a corner, but he winces every time he hears it.

Anyway, eventually he decides he can’t ignore it any longer and he sets off downstairs to investigate, but he’s a bit nervous about it, so he decides to take some kind of a weapon with him. There’s still books on the floor from when the bookcase went over so he picks up a really hefty one – a big old dictionary is my guess – and takes that. It’s the best he can do from what’s to hand. He creeps down the stairs and the piano note keeps playing over and over, annoying as a dripping tap.

Roland makes his way, quiet as anything, along the hallway to the front-room door. It’s open just a crack, but not enough to get a look at the piano. So he pushes the door ever so gently open. He’s trying so hard to be quiet, but oiling door hinges is still on his list of things

to do so it creaks, and then, all of a sudden, there’s this quick flurry of notes from the piano –

plink plonk plonk

– high to low, and a thump as the stool falls over, but by the time Roland gets in there’s nothing to see. So he stands there for a bit, and he’s sort of angry and relieved and scared all at the same time.

Once he’s calmed down a bit, he closes the lid over the keyboard. He wants to lock it shut but the key isn’t there, so he goes off to the bedroom to look in Aunt Helena’s music box. It’s a little carved wooden jewellery box that plays a clockwork tune when you open the lid. Helena kept all kinds of junk in it, so he thinks maybe that’s where the key will be. He finds the box and opens it up, and it’s still wound up, so it plays its little tune as he rummages around inside. And in among the earrings and buttons and foreign coins and an extra-strong mint and all kinds of other things he finds the piano key. And he also finds a small black leather collar with a bell on it: the one that Helena couldn’t get Oswald to wear. And now he remembers his aunt telling him about it, back when he was a little boy.

‘It was the only time Oswald ever scratched me,’ she said. ‘I tried to put that collar on him because he’d been killing birds and bringing them into the house. Feathers and guts everywhere. Terrible mess. So I tried to put the collar on him so the birds would hear the bell and keep away from him, but he wouldn’t have it. He hated it! He kicked and he squirmed and he fussed!

So I held him down tight and got the collar round his neck, and I was just trying to do up the buckle when he lashed out at me with his claws. Look, here, he cut the back of my hand, here, see. Do you see the scars? Gushing with blood, it was. And Oswald just jumped free and ran off. He didn’t come back for three days. I was so worried. And when he did finally come back, well, I never tried to put a collar on him again. And then eventually the birds just started to stay away anyway, as if they knew.’

It’s the most he can remember Aunt Helena saying to him in one go, and he smiles at the memory of it, but that isn’t why.

‘He hated it …’ he says.

And then he buckles the collar onto his wrist. And the next day passes without incident. And the next day, and the next.

He’s in The Crown a bit more regular for a while after that, and much more chatty too. He tells us about what’s been going on and how scared he got, how he’d started to imagine all sorts of silly things and, oh, isn’t it funny how ridiculous he’s been? But he’s fine now, he says. Just fine.

But he keeps wearing the cat collar on his wrist. He says, if you point it out, that it’s just to remind him of how silly he was,

starting to believe in ghosts, for goodness’ sake

! And we chuckle along with him. He’s a nice lad and we’re glad to see him out a bit more. And before long he’s only ever telling us all about how

the work on the house is going and not mentioning the cat at all. The collar’s still on his wrist, mind, but we don’t mention it. And he’s starting to feel quite at home in the village now, and he’s thinking maybe he won’t sell the house after all. Maybe he’ll stay. With all the work he’s done he’s got quite a reputation as a handyman now, and he does the odd bit of work for folk around the village, and round about. He thinks he can make a living at it if he works it right. It’s not as if he needs to earn much, and he can always let out a room or two in the house for a bit extra if need be.

A week or two later I’m passing by the house on my bicycle, and bless me if Roland doesn’t nearly knock me down in his car as he comes racing home. He gets out all flustered and fussing, and he won’t stop apologizing. I tell him not to worry, I’m fine. But why was he in such a hurry? Well, he tells me that Helena’s old lawyer is coming over with papers to finalize the transfer of the house. Once Roland signs, it’ll be all his. But he’d been out doing a little repair job for someone out in Freckingham, lost track of the time, and now the lawyer, Mr Buckley, is due any minute. And then he starts apologizing all over again and I have to get quite shirty with him to make him stop. Then I tell him congratulations – about the house, I mean – and I shake him by the hand and say how I hope he will stay because he’s such a fine young man and he’s a proper credit to the village.

Well, he’s a bit embarrassed by this – he’s rotten at

accepting compliments – and he really needs to get in and clean himself up before the lawyer arrives. So he thanks me, and dashes indoors, and I cycle off on my way. But as I do I wonder why it is that I don’t feel right. My guts are churning, like I’m worried about something, but I can’t think for the life of me what it could be. I’m still thinking about it when I arrive at Thornely, the next village over, where I’m picking up a dress I was having altered.

Well, it’s when I open the door to the shop that I realize what’s been bothering me. You see, there’s a bell that rings when the door opens and that makes me realize: when I shook Roland’s hand, there was no bell. He wasn’t wearing the collar on his wrist. And, well, that’s a relief because that’s a good thing, not anything to worry about, after all. I think it’s just grand that he’s finally seen sense and stopped wearing it, and it only makes me think of him all the more fondly.

I see the ambulance parked outside when I’m coming back the other way and, oh, it does give me a turn. My heart’s in my mouth as I stop, and I see poor Roland led out of the front door and helped into the back of the ambulance. He’s not making any fuss, mind, but his eyes are wider than I’ve ever seen anyone’s before, and he’s muttering quietly to himself, and he looks quite, quite mad. And those wide eyes are staring out from a bloody face. And that’s

not

swearing, because he is just covered in blood. I almost scream. His clothes are

torn and his skin is torn and he is covered in blood.

Mr Buckley says that’s how he found him. He thinks Roland did it to himself somehow, just went mad and slashed at himself with something sharp, and the police and the doctors are happy enough with that explanation too. They certainly can’t get any sense out of Roland to suggest otherwise. Mind you, they can’t find anything in the house that could have made those cuts either. I try to make a bit of a fuss about it all, but it’s not as if I’ve got any better explanation. Not one I’m happy to say out loud anyway.

The next day I bump into Mrs Curtain’s niece. It turns out it was her that Roland had been doing the work for the day before. She’s heading over to return Roland’s bracelet, she says, the one with the funny little bell on it. She saw him take it off before he set to unblocking her drain, and then he must have forgotten to put it back on again. She’d tried to take it back to him at the house but it didn’t seem like anyone was home so she’d just pushed it through his letter box.

‘He’s not still got one of them cats of Helena’s, has he?’ she says.

‘No,’ I say.

‘I didn’t think so,’ she says. ‘Only when I pushed the bracelet through, and the bell jingled as it hit the floor, well, I could have sworn I heard a cat. Mind you, if it had been, then, coo, it wasn’t a happy one!’ And then she’s off on her way, running to catch the bus.

I visit Roland for a while after that, at the special hospital, but he never speaks to me. Not to me, and not to any of the doctors and nurses neither. I keep going anyway, but he won’t touch the fruit I take him; it just rots in the bowl. And I talk to him. I try to tell him what’s been going on in the village, but he takes no notice.

After a while they ask me not to go any more. They say poor Roland has become quite distressed, and more and more difficult. You know, violent. He keeps scratching people. It’s very upsetting. He was always such a kind and gentle boy before, and now he’s just a devil.

Though apparently he does sometimes bring gifts for his nurses.

Mostly birds.

J

osephine, having come to a halt, sits in a curious frozen pose, her neck craning, her head tilted. Her eyes are bulging and seemingly staring, fascinated, at an empty corner of the ceiling. Her hands are clasped together over her chest, tightly entangled in a messy knot of bony fingers. Her mouth is puckered tightly closed, as if it’s trying to disappear altogether. She is humming very softly, and her head is nodding, just the tiniest amount, in time.

‘Thank you, Josephine,’ says Mr Osterley, and Josephine’s head dips forward as a grateful smile stretches out across her face. She looks like a child delighted by the praise of a parent.

‘Yes, thank you, Josephine,’ says friendly Frances. ‘I enjoyed that very much.’

Josephine grins all the wider. Jack even thinks that she might be blushing, though it’s a little hard to tell by candlelight. Some of the others offer up compliments, and Josephine shrugs and smirks in embarrassed delight. Jack mumbles something too, but he’s a little distracted. He’s thinking about the rumours he’s heard about this place, and just for a moment he’s wondering how much of what he’s heard can possibly be true.

‘Is shame the kitty cats is so horrible,’ says Piotr, and everyone else turns their attention to him. ‘I have kitty cat before, and she very good. She best mouse-catcher in my village. Even better than my sister. I still sometimes miss. Is sad.’ The exuberant forest of his beard closes up

around his mouth, leaving no trace of where it was, his head settles heavily, sinking down between the sad shrug of his enormous shoulders, his eyes glisten.

‘Oh, Piotr, lovey,’ says Josephine. ‘You poor lamb.’

There is a subtle hint of distaste in Mr Osterley’s expression now, but he keeps it out of his voice. ‘Thank you, Josephine,’ he says again, and raises the fingers of one hand in a tiny gesture directed at Josephine’s candle.

‘Oh yes, dear. Of course,’ she says. ‘Mustn’t go prattling on now.’ And she leans forward and, with a sharp stab of breath, blows out her candle, then shifts her chair back, away from the table and into the gloom.

‘Very good,’ says Mr Osterley. ‘And now perhaps, Piotr, you might take your turn?’

Jack relaxes a little at this, happy not to have been chosen, and Piotr cheers up considerably too. His gleeful grin is exhumed from his beard.

‘Ha! Oh, yes please, mister. It is pleasure. I have very good tale for you. Is story from big time ago in my country that my grandmother tell me when I was boy. You will like very much, I think. Oh yes. Is like fairy tale, only is true. My grandmother swear by her moustache that is true. So must be so.’

Piotr settles himself, pulls his mighty torso upright and sits up very straight. He scans a stern look around the table, ensuring everyone’s attention. And then he begins.

O

nce, in land near mine, there is woodcutter in little village. One day he go out to chop down big, mighty oak tree. He is not long from being started when skinny fellow appear, all sweaty and running fast, and he say: ‘Sell me horse.’ But woodcutter, he need horse, of course, so he say: ‘No, thank you very much.’ But sweaty fellow, he go to horse anyway, like he is to steal it. So woodcutter hit him on head with axe. Not with sharp end of blade, only with back to make him stop, but still he kill sweaty fellow. Is big axe for cutting of big tree, is very heavy.

Oh no!

he think. Dead sweaty fellow is dressed all fine. Maybe he is important man and now woodcutter has killed and is make the big trouble.

Then King’s knights appear, and woodcutter think,

Oh no, is very bad!

But no! Dead man is bad prince from country over river. Bad prince, he was running away from King’s knights. King’s knights very happy bad prince dead. They take woodcutter to see King, they say he big hero. King, he give woodcutter many gifts as reward; songs are written saying how brave he is; his fame grow, and pretty girls of kingdom dream of him. Now woodcutter, he forget all about his village, hang up his axe

on wall of house near palace, and he start spending his money on pleasures of city.

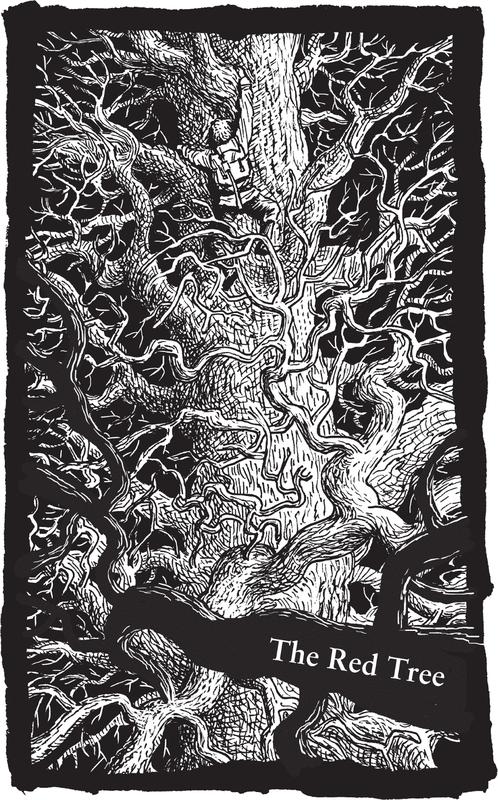

But near village, in far part of kingdom, there is dark forest where many young men disappear. Nobody know why. They go into forest – maybe hunting, maybe looking for mushrooms, maybe picking flowers for pretty girl, who know? – and they never come out. People there, they very unhappy, and frightened, you know? They tell all kind of tales. They say murderous beasts in forest, or they say evil spirits, but story that they tell most say there is red tree that lures men to doom. Is very bad. They scared and they don’t know what to do. So when, you know, story-singing man … er, what is word? Minstrel! Yes, minstrel. When minstrel come to village and sing song about woodcutter’s brave deeds, they think: here is man to help us, and they send message to King. And so woodcutter, he is summoned to palace.

He get there, and he wait a while, and a while more, and then big tall fellow who is chamberlain come and take him to King.

‘Your Majesty,’ say woodcutter, and he kneel down. ‘How might I serve you?’

The King, he has forgot all why woodcutter is here, so he ask chamberlain, and then chamberlain start to explain to King. And then after little while King is bored and so he tell chamberlain to deal with woodcutter while King go off and have nap.

‘Is Curse of Northern Wood,’ say chamberlain. ‘Is

problem there, and King, he like you go there and solve, yes?’ And he say it like question, but is not question that woodcutter should answer. So woodcutter he stay quiet. He clever biscuit, but he look not so keen on going to Northern Wood.

‘You very good before, when you kill evil Prince Frederick from land of enemies,’ say chamberlain. ‘Land of enemies make war with us, we win war, we make country bigger, King make more money. Is good thing. King, he hope you like house and lands and money he give you?’

‘His Majesty very generous,’ say woodcutter.

‘Yes indeedy,’ say chamberlain, and he roll his eyes. ‘So, King have favour to ask.’

And then chamberlain explain about Northern Wood, and people who go missing, and legends about red tree, and there is too other legends about silver ghost, and he roll his eyes again and say: ‘Tch! Country folk! We would take no notice, only Queen’s maid’s cousin live in village, and Queen say we will do something. So we send you with guards, make sure you arrive all safe. Make sure no bandits in woods slow you down. Then you chop down red tree, lift curse, calm down superstitious local peoples, and everybody happy.’ And this time he not even pretend to make question. Woodcutter he have no choice.

‘Is my honour to serve King,’ he say.

‘You bet your boots, mister,’ say chamberlain. ‘You leave at dawn.’

The next day is long ride to Northern Wood. Woodcutter and escorts not waylaid by bandits on journey. Is just boring. And guards boring too. Is enough to tell you: all very glad to arrive at village.

Tomas, son of miller, see woodcutter and guards coming and run to tell village elders, and so they come out to greet. But when they see woodcutter and guards they not so happy.

‘Is that it?’ say one of them. ‘We send to King for help and all he send is two fat old soldiers and dandy. And for this we are paying taxes?’

Guards not like being called fat and old (because they fat and old) so they say: ‘We not stopping. We here to deliver this fellow all safe and all sound. We go now.’ And they go.

Elders look at woodcutter. One of them say: ‘What you meant to be, anyhows?’

Woodcutter get down off horse and try to stand all brave and manly and impressive.

‘I am woodcutter Yan Haval,’ he say, ‘hero of Southern Woods, slayer of evil Prince Frederick from lands to north, saviour of kingdom and proud servant of King Emil the Wise!’

‘

You

are Yan Haval?’ say elder. ‘You shorter than ballads say. Oh well. You bring axe?’

‘Yes,’ say woodcutter, and he sigh. ‘I bring axe.’

‘I suppose you will do. Come have soup and we talk.’

So they take him to house, give him soup and bread

and they tell him legend of silver ghost and red tree. Only they argue and can’t agree how story go. There is red tree and there is silver ghost, and some children and menfolk go missing in woods, and some cattle and some plants die. This much they all agree. But rest? Oh boy! One say silver ghost live in red tree. One say, no, you fool, red tree grow fruit to protect from silver ghost. Another one say, you both wrong, silver ghost guard red tree. This all go on very long time and woodcutter very bored. Also, soup is no good.

Woodcutter say, ‘You want me cut down red tree?’ and his forehead go all wrinkles like ploughed field. The elders, they have little chat between them, all quiet and whispers and secrets. Then they say to him: ‘Yes, please, thank you very much.’

So they draw him map. Is pretty bad map, because of arguing, but give some idea of where is red tree, and woodcutter wanting to leave, so he pick up axe and walk off toward dark woods. As he go he pass children singing in street, teasing younger boy. They sing:

Child don’t stray in dark, dark wood,

For whether you bad or whether you good

Where the red tree grow

From the bones below

The silver ghost will drink your blood.

Is such nonsense, think woodcutter to himself. Such silly superstitions! I find this red tree, I chop it down,

I back to city in time for market day. And he smile to himself at thought of chamberlain’s daughter, who he promise to take around market. She very pretty girl with hair all shiny shiny and skin like moon on water. So he stride through woods, following way marked on terrible map, and he look for red tree.

Now, is funny thing: see, he know full well all village folk just silly billies with their fears and superstitions, but as light fade and shadows grow long and dark, woodcutter, he start to find woods all scary and sinister. He feel like when he was little boy. And he realize he see and hear no birds and no animals, all he hear is own footsteps, fern and bracken under feet, sometimes crunch of twig that make heart thump harder in chest. And it get darker and all little shadows join up into one big shadow, like monster made of night that loom over him.

Now woodcutter, he is used to forests and woods, but even so, he find he feel afraid, just a little bit. Is very annoying and he tell himself off. Silly man! And he set down his pack and he make camp for night. And he make nice fire – to keep warm, not because he is afraid of dark, oh no. And when he sleep and he keep waking up, is because ground is hard and uncomfortable, not because sound of wind through high branches make him anxious, and not because of dreams of pale figure, glowing all silver, walking toward him with arms all outstretched.

Woodcutter wake at dawn. Fire is out, and he cold

and tired, and he not think in straight lines, and dreams he had still in head little bit, like morning mist not cleared, like echoes. But then he start to see right, and head start to clear, and echoing sounds from dream are still there. Is real sound, not dream. And is close.

Something coming.

He really scared like little boy now, so he do what little boy do and he think:

I climb tree and hide

. When he little boy he hide from village children up tree. Most people is never looking up. Is good hiding place. So he grab pack and he look all quick for good tree, and he very lucky man because straight ahead is very good tree. Bark is pale and stand out in twilight, like is saying: ‘Pick me! Pick me!’ And has low branches make easy to climb.

He race up quick (is like up ladder is so easy) and he find comfy branch, is maybe twenty feet up, and he settle. And he stay very still and he look down through branches and he look for whatever is making noise. Is rustling leaves and cracking twigs, and is louder, so must be closer now, but still he cannot see what. He shift body, just very little bit, and all slow and quiet, looking down all different angles, through all different gaps in criss-cross branches. Dawn light is all broken up and branches all shiny frosty, they go all wobbly wibbly for his eyes, make head dizzy. He blink all tight and shake head and he look again, and he hear his own breathing, like sound of sawing, and see breath all clouds in cold morning air.

And he wait and he watch, and noise still is louder, but still he see nothing. And still, and still … Then – at last! – he glimpse some moving thing in down below. Not silver ghost, though. Is something dark. What is? He remember chamberlain talk of bandits in woods. Is man maybe? He see again something, just for little moment, and he hear all snuffling and grunts. Is no man. Then it move to where he see good through big gap in branches, and he see is boar! Is big fat boar! And boar is very not ghost! Woodcutter, he laugh, all relieved. Very short laugh like stab or punch. ‘Ha!’ Like that. He feel like fool. He laugh again, loud, with head back and mouth all open wide.

This when he see. Through tangly branches above is something glinting all sparkles near top of tree. He decide to climb and see. Is easy at first, like before, like tree is helping. Always is place for foot to go, always is branch for hand to grip. So he climb up very fast, and he keep seeing glinting shining metal above but only little bit, and always not clear what is.

But then is tricky bit. Is place where big branch has broken off. Is only jagged sharp stump that stick out from trunk, then next branch up is long way and hard to reach. He take off pack, and jam into forked branch at feet, then he jump up. Is brave thing. Is very high up now and if he fall, is killing him. He grab branch above with both hands, but one slip off, and he swing and he nearly fall. Leg bash into sharp stump of broken branch and he cry out painful. But he hang on, and he

grab on with other hand and pull up himself. He look at leg. Is cut all bloody, but not so bad.

He look up again. Flashy metal shining is easier to see now, but still not see what is. And now, also above, he see dark shapes in branches, maybe like nests or some other something like? But big nests. He climb some more. His leg hurt little bit and he go slower and have to concentrate quite hard, but he go up and up OK, and eventually he reach the shiny metal thing and is medallion. Is pretty thing. Maybe is good gift for chamberlain’s daughter. He wonder how is getting there up tree. Maybe bird carry it up and it fall from nest. He look up now at nests.

Is not nests.

Is raggedy cloth, all torn up and tangled, rags swaying in breeze. And in rags is bones. Is human bones. Woodcutter, he see ribcage first, then other thing else. Maybe arm, maybe leg. And is more nests than one. Is five or six, all same, all rags and bone bodies. He make no cry, but his breath go all fast and loud, and his heart same. He think he is far enough high up tree now. He think now he go down.

But he look down and see no way. Branches is all wrong now. He try to see way he come up, but is not what he remember. Is very strange. He trying to reach leg down one way and he scrape cut against knot on trunk and, oh, it hurt very much! He howl all loud, then he try to pull leg back up, but somehow is stuck. Foot is caught between two branches somehow, and

pain is hot and wet. He reach down left hand to feel, bring back up to face. Fingers dripping very red. Is bad cut. And foot still stuck.

He reach up high and take hold of branch above head, ready to pull leg free with strong pull. With bloody hand he grip branch tight and he see blood drip onto bark, run into grooves in bark. Blood is drawing red lines on branch and he is watching.

And blood disappear.

Is like blood evaporate. Or is like blood is sucked into pale bark. Is very scary strange, even to brave woodcutter. And seeing is making woodcutter all stiff and still, and he is feel like leg is stuck more tight now. He try to pull up, but only more pain. Is not moving. If only he have axe! But is below with pack. He tell himself when back down to ground, he is making revenge and chopping tree down. Is good practice before he chop also down red tree. And he smile one second.

Then he scream.

Is new pain now in right hand. He twist his head and look up and he see impossible thing. Is new twigs grown from branch this second. Is like fingers grasping hand. Is crushing hand. He try to pull it free but is no good. Twigs go more thick and more tight and hand is gripped very, very strong. So now is one leg and one hand trapped and is much pain. Woodcutter pull and twist and kick, wild and all panic, but is no good. More twigs grow, and they go thicker and they grip free hand and leg and they pull them and make still.

So now woodcutter all still all over. He cannot move one thing except to twist his head a little. And he call out to empty forest for help. He cry and scream. But only for just little while, because is new branch growing, wrapping round chest like is big snake, and it go tight, and more tight, and is squeezing air out of lungs. Is crushing big strong hero, Yan Haval, like is eggshell.