This Great Struggle (41 page)

Read This Great Struggle Online

Authors: Steven Woodworth

Sherman opened the ball the next morning with his attack on the Confederate right, which Grant was counting on as his main blow. The mountainous terrain around Chattanooga was new to both armies and to their commanders, and the massive terrain features had much different tactical effects than did analogous features in the gently rolling terrain in which they had previously fought. Ridges like Lookout Mountain had proved surprisingly vulnerable to direct assault. Now Missionary Ridge turned out to be a much stronger position against a flank attack than anyone had previously imagined. That factor, along with the presence of Bragg’s best division commander, Major General Patrick R. Cleburne, on the Confederate right was enough to stop Sherman’s assault in its tracks.

Grant had anticipated subsidiary pushes from Hooker against the Confederate left flank at the other end of the ridge and from Thomas, with the Army of the Cumberland, against the enemy’s center. Grant had not expected much from these efforts beyond diversion of the enemy, and so far they had not delivered even that. Hooker’s attack against the south end of Missionary Ridge was delayed by an unbridged creek on the way there, and Thomas showed no inclination to make so much as a threatening movement on his front.

Grant’s headquarters were near the center of the line, and so in mid-afternoon he approached Thomas and asked if he thought it would be a good idea to threaten the Rebel center. Thomas, who was scrutinizing the Confederate line through his field glasses, ignored Grant, though he could hardly have failed to hear him. Some minutes later Grant simply ordered Thomas to advance his army and take the first Confederate line of rifle pits, which was at the base of Missionary Ridge. Some time later when the Army of the Cumberland still did not advance, Grant again prodded Thomas, who lamely explained that he had given the order but did not know why it was not being carried out. Finally, late in the afternoon Thomas’s army did advance, though he had neglected to see to it that his division commanders knew their objective. Some units thought they were driving for the top of the ridge, others that they were to stop after taking the first Confederate line at its base. Still others had no idea where they were to stop.

Fortunately for Thomas’s men, the Confederate entrenchments at the base of the ridge were lightly manned, and about half of the units in them had orders to retreat after two volleys. Their hasty departure was demoralizing to the remainder of the Confederates on that line, who had no idea of any such orders. Thus, the first Confederate line fell easily into Union hands. Confusion then reigned in Union ranks as some units started immediately up the ridge and others halted uncertainly. Eventually, division, brigade, and even regimental commanders, recognizing that their troops were taking heavy fire from the crest of the ridge, made the decision to advance, and all five attacking divisions went up the slope, though now in very ragged formation.

Like Lookout Mountain the day before, Missionary Ridge proved surprisingly vulnerable to direct attack, its steep slope and rugged folds providing much cover for advancing attackers. Eager to avenge their defeat at Chickamauga, Thomas’s troops pressed doggedly upward and broke the Confederate line in several places virtually simultaneously. At almost the same time, Hooker finally got his troops onto the south end of the ridge, adding to the Confederate discomfiture. Resistance quickly collapsed, with all of Bragg’s army in headlong flight except for Cleburne’s still-resolute division, which covered the rest of the army’s retreat much as Thomas’s command had done for the Army of the Cumberland after Chickamauga. That, along with the rapid approach of night, precluded effective pursuit and allowed Bragg’s army to escape, minus several thousand prisoners and several dozen cannon left in the hands of the exultant Federals.

YEAR’S END, 1863

Up in Knoxville, Longstreet heard of Bragg’s defeat and made an attempt to storm a key Union fort near the city. Like almost everything Longstreet did during his western sojourn, the attack was woefully mismanaged and developed into a resounding failure. Grant, in the wake of his Chattanooga victory, dispatched Sherman and his hard-marching troops to deal with Longstreet. As Sherman’s troops neared Knoxville, Longstreet broke off the siege and retreated northeastward into Virginia. Never again would Longstreet or any large detachment of troops from the Army of Northern Virginia serve in the war’s western theater, and never again would the Confederacy make such a concerted effort to turn the tide of the war in this decisive theater and regain all that it had lost since the debacles at Fort Henry and Fort Donelson.

Grant’s resounding victory at Chattanooga capped a six-month period of dramatic Union successes including the culmination of the vast and complicated Vicksburg Campaign as well as victories at Gettysburg, Tullahoma, and Chattanooga with only the temporary setback of Chickamauga. In response to these encouraging developments, pointing to eventual restoration of the Union and an end to slavery, Lincoln issued a proclamation establishing November 26 as a nationwide day of thanksgiving to God. This nationalized a holiday that had been traditional for many years in the New England states as well as in some of their western progeny. Peace did not seem as distant as it had only a few months before.

On November 19 Lincoln had delivered “a few appropriate remarks” (so read the note inviting him to speak) at the dedication of a new National Cemetery at Gettysburg, established to accommodate the many thousands of Union dead from the preceding summer’s battle. In one of the most eloquent speeches ever made in the English language, Lincoln explained in clear and forceful language and with striking brevity why the North was fighting and why it must fight on to final victory. “Four score and seven years ago,” the president began, referring to the writing of the Declaration of Independence,

our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation, so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate, we can not consecrate, we can not hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

2

10

FROM THE RAPIDAN TO THE JAMES TO THE POTOMAC

THE WAR ENTERS ITS FOURTH YEAR

T

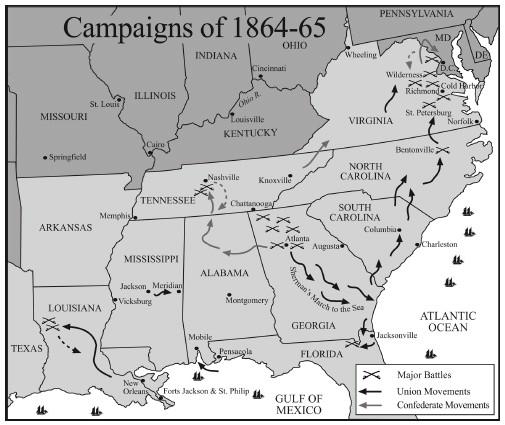

he year 1864 dawned amid high hopes in the North. The victories of the preceding six months made final triumph seem within reach before another new year dawned. In Grant, Lincoln had finally found the general he felt confident could see the conflict through, and the northern people shared their president’s confident expectations for quick and decisive battlefield victories as soon as the drying of the South’s dirt roads made it possible to open the campaigning season again that spring. With Grant in mind, Congress recreated the rank of lieutenant general, which previously only George Washington had held (Winfield Scott had ranked as a brevet, or honorary, lieutenant general). After satisfying himself that Grant had no ambitions for the 1864 presidential election, Lincoln nominated him for the rank, and Congress promptly gave its approval. Grant was now the highest-ranking Union general, and Lincoln formally appointed him as general in chief of all the Union armies. President, Congress, and public eagerly awaited the coming of spring and Grant’s devastating new campaign.

Surprisingly, Confederates also looked with confidence to the resumption of active campaigning in the spring of 1864 despite the string of defeats with which they had finished out the year 1863. This curious state of mind sprang in part from their own residual belief in their inherent superiority to northerners and in part from focusing on a number of Confederate victories in minor battles during the winter and early spring of 1864. Rebels could point with pride to their side’s dramatic, if strategically relatively insignificant victories over secondary Union expeditions or garrisons at places like Olustee, Florida; Sabine Pass, on the Texas–Louisiana line; Fort Pillow, Tennessee; or Mansfield, Louisiana. Confederate forces had also held on to Charleston, South Carolina, including a battered but still defiant Fort Sumter, despite the Union’s joint army–navy expedition to take it, including several ironclad warships and several thousand ground troops. These victories all put together did not equal half the strategic importance of a single Vicksburg or even a single Chickamauga, but they sustained white southerners in the sublime confidence that they were bound to win the war in the end.

Adding to Confederate optimism was the fact that Lincoln was up for reelection in the fall of 1864. There was never any question of postponing or canceling the election. The northern voters were going to have the chance, in the middle of a war for the nation’s survival, to express—and enforce—their opinion as to whether that war should continue. If, as seemed likely, a “peace Democrat” won the Democratic presidential nomination, the election might well become a referendum on the war. If the Confederate armies could thwart Union plans for 1864 and exact heavy punishment in doing so, the northern electorate might become demoralized enough to choose a candidate who would give up the war and accept Confederate independence. As events were to prove, both Union and Confederacy entered the fourth year of the war with far more optimism than was warranted.

The war was changing. The fight at Fort Pillow, in which Confederate cavalry raiders under the command of the unorthodox but highly successful Nathan Bedford Forrest captured a minor Union garrison on the Mississippi River, also marked a disturbing trend toward more violence in the war. Almost nothing enraged white southerners more than the presence of tens of thousands of newly freed African Americans in the ranks of the Union armies. Since the first black soldiers had donned the blue a year before, Confederates had voiced many threats, both formal and informal, of what they would do to black soldiers and their Union officers. President Davis himself had decreed that captured black soldiers would be treated not as prisoners of war but as recovered slaves, and their white officers, if captured, would be turned over to state authorities for disposition under the laws governing the incitement of slave rebellion—an offense punishable by death. Lower-ranking Confederates, from brigadier down to private, penned in letters and diaries and shared with each other their more straightforward threat to take no black prisoners at all. Their attitudes are revealing about the racial motivations of Confederate soldiers.

The case of Fort Pillow became an early example of the fulfillment of these threats. There attacking Confederate troops killed black Union soldiers as they attempted to surrender and killed some who apparently had successfully surrendered a few minutes before. It was one of the most famous but far from the only case of such behavior on the part of Confederate troops, who went almost mad with rage at the sight of black men in blue uniforms bearing arms against their former masters. This new element of brutality raised the overall level of violence in the war, as black and sometimes white Union troops learned of the Confederate massacres and sometimes carried out small-scale, unauthorized retaliation, especially in the heat of battle.

Confederate policy toward black Union soldiers added to the horrors of war in another way. Since official Confederate policy regarded captured black soldiers not as prisoners of war but rather as slaves to be returned to bondage, the Confederacy refused to exchange such captured blacks. Union authorities, particularly Grant, believed themselves obligated to protect the rights of every man wearing the uniform of the United States. They therefore maintained that no exchanges could take place unless both black and white soldiers were released without discrimination. On top of this, the parole system was already in bad shape after the Confederacy had returned to the ranks, without exchange, the paroled prisoners of Pemberton’s army surrendered at Vicksburg.

By the beginning of heavy fighting in the spring of 1864, parole and exchange had ceased completely. As prisoners were taken, they went into prisoner-of-war camps that had been designed for far smaller numbers of men and a system that had never foreseen such a massive prison population. The Confederacy had difficulty feeding its own troops, and the prisoners penned up by the tens of thousands in open stockades like that at Millen, Georgia, or the infamous Andersonville prison in the same state had a much lower priority. Camping in one place for an extended period, whether prisoners or not, was statistically the most dangerous thing Civil War soldiers did since the stationary camp promoted the spread of the war’s most efficient killers, disease germs. In the prison pens of the South, disease raged among populations weakened by malnutrition, adding to the horrors of the last year of the war. The only war crimes trial arising from the Civil War ended in the hanging of Andersonville commandant Major Henry Wirz.