This Great Struggle (45 page)

Read This Great Struggle Online

Authors: Steven Woodworth

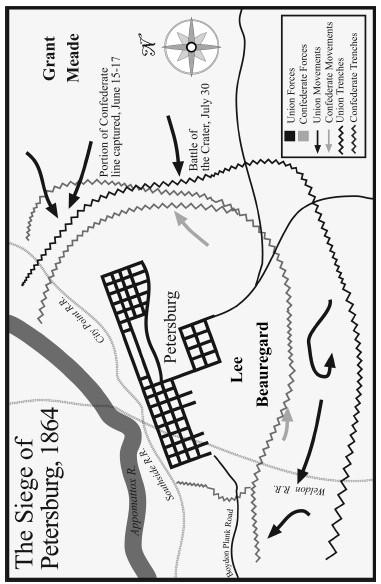

While Early’s troops marched west, Grant’s marched south. His leading elements reached Petersburg on June 15 to find the city defended by only very scant Confederate forces, part of the small command under Beauregard that had been holding Butler bottled up in Bermuda Hundred. The Union troops swarmed over the fortifications ringing Petersburg, but as the outnumbered Confederates desperately tried to form another line and dig in even closer to the town, the commander of the leading Union corps, afraid he might have misunderstood his orders, halted his troops. Beauregard used every hour’s delay to bring up more troops and entrench those he had. By the next day, Grant and Meade were on the scene and ordered renewed attacks, but the Army of the Potomac was worn out and bled white by the past six weeks of fighting. Its troops did not attack with the same drive and eélan they had shown in the Wilderness and at Spotsylvania. Despite a continued heavy Union preponderance in numbers, a series of poorly coordinated, halfhearted assaults over the following three days failed to break through the growing numbers of Confederate defenders and their increasingly stout second line of fortifications.

Since the Federals had first appeared in front of Petersburg, Beauregard had sent one urgent message to Lee after another, apprising him of the situation and begging him to send troops. Lee had remained steadfastly incredulous. So skillful had been Grant’s departure from Cold Harbor and march south that although Lee had been expecting Grant to move against the James River and knew that the Army of the Potomac was not present at Cold Harbor, he still could not believe that the Federals had already reached and crossed the James and were threatening Petersburg. The truth finally began to dawn on him during the night of the seventeenth to the eighteenth of June, and before daylight he dispatched two divisions to reinforce Beauregard. Even with these additional troops, Beauregard faced long odds at Petersburg, but the tenacity of his troops, the enormous advantages of the entrenched defensive, and the sluggishness and lack of aggressiveness by the battle-weary Army of the Potomac combined to prevent a Union capture of the vital rail junction.

With the rest of Lee’s army rapidly filing into the new inner line of Petersburg fortifications and removing all further prospect of taking the place by storm, Grant settled down for a quasi siege of the city and its northern neighbor Richmond. He could not cut off the flow of food into the two cities, but he could press his entrenchments ever closer to the Confederate defenses, pounding them day after day with siege artillery and constantly stretching his lines westward around the south side of Petersburg to threaten the two rail lines that had now become the last lifelines of the Confederate capital. Grant had wanted to avoid such a siege because it would be long and trying on Union morale. Lee had hoped to avoid a siege because he knew that in military terms its only possible outcome would be his defeat—provided that Union morale and political will remained steadfast.

Meanwhile out in the Shenandoah Valley, Hunter’s troops had been living off the land and causing consternation and outrage among the populace by acting as if they were in enemy territory in the midst of a hostile civilian population. On June 11, Hunter ordered the Virginia Military Institute burned as well as the house of former Virginia governor John Letcher, who had issued a proclamation calling on civilians to wage a guerrilla war against Hunter’s forces. By June 18, as Hunter approached Lynchburg, Early was on hand with his corps. Reinforced by the remnant Confederate forces that had been operating in the valley, Early’s command was strong enough to convince Hunter to withdraw. The Union general retreated with his force into the Allegheny Mountains of West Virginia, leaving the Shenandoah Valley wide open for Early.

Early marched his command down the Shenandoah Valley and on July 5 began crossing the Potomac into Maryland. The next day, as the tail end of his column was completing its crossing of the river, Early’s vanguard took Hagerstown, Maryland, and demanded that the municipality pay twenty thousand dollars or be burned. The townsmen paid up. In Washington, seventy-five miles to the southeast, consternation reigned, as officials made hurried preparations to defend the city. Since Grant had pulled nearly all of the garrisons out of the forts around the national capital to reinforce the Army of the Potomac, the city was vulnerable. Halleck’s frequent telegrams had kept Grant apprised of the situation, and the latter now decided he would have to detach troops from the Army of the Potomac to meet the threat. One division of the Sixth Corps pulled out of its trenches around Petersburg; marched down to the James River landing at City Point, Virginia, where Grant had recently established his main staging base and forward supply depot; and from there went by steamboat to Baltimore.

On July 9 Early’s men marched into Frederick, Maryland, scarcely fifty miles from the capital, where they demanded and received the sum of two hundred thousand dollars to leave the city standing. About ten miles southeast of Frederick, the road to Washington crossed the little Monocacy River. On the far bank of the Monocacy waited a force of just under six thousand Federals, inexperienced militia stiffened by the Sixth Corps division Grant had first dispatched north. The force along the Monocacy was under the command of Major General Lew Wallace, who had disappointed Grant at Shiloh and would later go on, while serving as governor of the New Mexico Territory after the war, to write a novel titled

Ben Hur

. On this day Wallace had the unenviable task of delaying Early’s march. He did not know whether the Confederate general’s target was Washington or Baltimore, but he had to stall him long enough for reinforcements to reach those cities. At the Battle of the Monocacy he accomplished just that, delaying Early for most of a day, although his militia was routed and his more experienced troops had to make a fighting retreat.

On July 11 Early’s troops swarmed into the suburbs of Washington. In Silver Spring, Maryland, they burned the house of U.S. Postmaster General Montgomery Blair. Pressing on, they arrived within range of the Washington fortifications, where they skirmished for several hours. By this time the defenses were manned no longer by government clerks and soldiers in the final stages of recovery from wounds or sickness but rather by the sturdy veterans of the Sixth Corps, the two remaining divisions of which Grant had dispatched from City Point as the reports from Washington had grown more dire.

Early’s troops could accomplish nothing against powerfully built fortifications, strongly held by experienced soldiers, and so after exchanging fire for several hours, they retreated, though not before Lincoln himself had visited a frontline fort and observed the fighting. The president showed great curiosity and perhaps a desire to share at least a small taste of the experience of battle into which it had been his duty to send so many men. According to one account, a junior officer a short distance down the line, not recognizing the tall man in civilian suit and stovepipe hat placidly gazing over the top of the parapet, had shouted, “Get down, you fool.” Lincoln seemed to smile quietly to himself and, after a final look at the battlefield, stepped down to a place of greater safety.

Early’s small army marched west again, back toward the Shenandoah Valley. Early detached a force to stop by the south-central Pennsylvania town of Chambersburg and demand a ransom of one hundred thousand dollars in gold or five hundred thousand dollars in U.S. currency. When the unfortunate townsmen, who had been plundered by Lee’s army the year before, could not come up with the money, the Confederate officer commanding the detachment had much of the town burned. Confederate troops also went out of their way to find the house of Republican newspaper editor Alexander McClure, on the north side of town, away from the other fires, and burn it too.

As Early’s army had marched away from Washington, the Confederate general had profanely boasted to one of his officers that he thought he had badly frightened Lincoln, whose head and stovepipe hat above the Union parapet none of the Confederates seems to have recognized. In that much Early was clearly mistaken. The chief purpose of the raid that had taken the Rebels within sight of Washington had been to create within the Union government and high command sufficient alarm to force Grant to break off the siege of Richmond and Petersburg and hurry the Army of the Potomac back toward its namesake river to save the national capital. Lincoln had sufficient confidence in Grant to leave military matters largely, if not quite entirely, in that general’s capable hands, and Grant did not scare easily. He had detached just enough troops to guarantee the security of Washington and in just enough time to get there. It would still be necessary to find a way to deal with Early, who hovered annoyingly with his army in the lower (northern) Shenandoah Valley, but the siege of Petersburg and Richmond ground on unabated.

11

THE ATLANTA CAMPAIGN

FROM DALTON TO THE ETOWAH

S

imultaneous with the Army of the Potomac’s offensive that Grant supervised in Virginia, Sherman launched an offensive of his own with the Union’s three prime western armies—the Army of the Cumberland, under the command of Major General George H. Thomas; the Army of the Tennessee, under the command of Major General James B. McPherson; and the Army of the Ohio, under the command of Major General John Schofield—about one hundred thousand men in all. On the same May 4 that the Army of the Potomac crossed the Rapidan on its way to encounter Lee in the Wilderness, Sherman’s armies began to advance from their camps around Chattanooga. They made contact with main-body Confederate forces on May 7.

Except for the absence of Robert E. Lee on this front, the challenge facing Sherman in North Georgia was even more daunting than the tangled Wilderness and the succession of rivers that lay in front of Grant in Virginia. Three significant rivers lay athwart Sherman’s path: the Oostanaula, the Etowah, and the Chattahoochee. Between them high, sometimes craggy ridges barred the way. Across all this Sherman would have to depend for all his supplies on a single-track railroad, the Western & Atlantic, which ran from Chattanooga to Atlanta. Even north of Chattanooga his supplies would still have to travel down a single set of rails all the way from Louisville, Kentucky, three hundred miles farther north, and almost the whole route, from the depots at Louisville to the rear areas of Sherman’s armies, would be within striking range of raiding Rebel cavalry who had already demonstrated their propensity for tearing up tracks. Sherman had small garrisons in blockhouses guarding key bridges and trestles and had pre-positioned spare parts and repair crews to keep the trains rolling and the hardtack reaching the haversacks of his soldiers. An important element of Sherman’s genius was his skill at logistics, the business of keeping his army supplied.

The first obstacle Sherman would have to negotiate was steep and rugged Rocky Face Ridge, lying across the Western & Atlantic and stretching many miles on either side. Sherman’s opponent, Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston, had entrenched his army, named the Army of Tennessee but not to be confused with the Union Army of the Tennessee, along this seemingly impregnable position with its greatest strength flanking the gap through which the Western & Atlantic crossed the ridge, a deep declivity the locals called the Buzzard Roost. Johnston devoutly hoped Sherman would hurl his troops against it so that he could slaughter them. Johnston had not, however, taken the trouble to reconnoiter the southwestern reaches of Rocky Face, where a winding narrow valley called Snake Creek Gap pierced the ridge and emerged only a few miles from the Western & Atlantic fifteen miles behind Johnston’s position and about five miles north of where the railroad crossed the Oostanaula River at the little town of Resaca.

Sherman did know about Snake Creek Gap. Among this remarkable general’s many striking qualities were a strong memory and a sharp eye for terrain. As a junior officer back in the 1840s Sherman had been stationed in North Georgia and had ridden all over these hills on army business. The consequence was that in this campaign in the Deep South, the Union commander knew the terrain better than his Confederate opponent. Sherman planned to turn Johnston’s powerful position on Rocky Face Ridge by sending the Army of the Tennessee through Snake Creek Gap while the Army of the Cumberland and the Army of the Ohio feigned an all-out frontal attack.