This Great Struggle (44 page)

Read This Great Struggle Online

Authors: Steven Woodworth

Almost incredibly, the fighting around the Bloody Angle continued throughout the daylight hours of May 12 and then through most of that night, amid pouring rain, until by 3:00 a.m., May 13, Lee’s troops had completed a new line of breastworks across the base of the Mule Shoe, sealing off the sector for which the Federals had fought for almost twenty-four hours. The Confederate survivors of the fight at the Bloody Angle then fell back to the new line, leaving Grant’s troops in possession of the Mule Shoe, now a smoking, steaming wasteland of churned mud, shredded foliage, and thousands of corpses, some of them almost trampled into the mud.

The result was far from what Grant had intended. Hitherto in the war his generalship had been reminiscent of a swordsman who had defeated his opponents by lightning rapier thrusts. Now the weapon in his hand, the Army of the Potomac, seemed less like a precision sword than a heavy club. There was no denying these eastern soldiers would fight with ferocity and die with sublime courage, but the army’s staff and command echelons never seemed to get the knack of Grant’s style of warfare. The result was the drawn-out Battle of Spotsylvania with its appalling casualties.

Grant probed hard at Lee’s lines on May 18, and Lee returned the favor the following day. Each learned at some cost that the other was still holding his entrenched lines in more than ample force to slaughter any number of attackers. Grant was reluctant to continue the sort of massive bludgeoning match the campaign had become and still hoped to win a decisive battle rather than grind his foe down by attrition. Accordingly, on the night of May 20, Grant put his army in motion, once again swinging to the southeast in hopes of turning Lee and forcing the Army of Northern Virginia into a stand-up fight in open country.

Once again Lee reacted quickly, putting his own army on the march the following day and on May 22 took up and entrenched a strong position behind the North Anna River, once again blocking Grant’s advance but twenty-five miles closer to Richmond. The Army of the Potomac arrived the next day, and two of its corps reached the southern bank of the North Anna River, one near Jericho Mill and the other ten miles or so downstream near Chesterfield Bridge. Moderate fighting flared on both fronts. On the twenty-fourth, however, the Army of the Potomac’s center found the river strongly defended near Ox Ford and was unable to force a crossing.

In response to the successful Union crossings on the twenty-third, Lee had arranged his army in a sprawling, upside-down V with only the point and a brief segment of the western leg touching the river near Ox Ford. This left the Army of the Potomac in three separated segments—one south of the river on the upstream side of Lee’s entrenchments, another south of the river on the downstream side of Lee’s entrenchments, and the third north of the river in the middle. River crossings by pontoon bridge made large troop movements between these segments difficult. In theory, Lee, who had recently received nine thousand reinforcements comprised of troops released by the failure of Butler’s and Sigel’s offensives, could mass his forces against either end of Grant’s line with a heavy local advantage in numbers, while Grant would have difficulty reinforcing or withdrawing those isolated corps.

During the Civil War, such theoretical advantages rarely translated to reality, and the North Anna was no exception. Lee was sick in his tent, and of his experienced corps commanders, Hill was also sick, Longstreet was still out of action with his Wilderness wound, and Ewell was breaking down under the stress of the preceding three weeks of campaigning. Hill and Ewell were still on duty but functioning very poorly. From his cot, Lee was unable to give sufficient direction to Longstreet’s less experienced replacement to carry out such a mass attack. Whether such an assault would truly have been decisive is doubtful. Such efforts almost never were, and had the attackers found the Federals entrenched, as was likely, the advance would likely have been short and bloody.

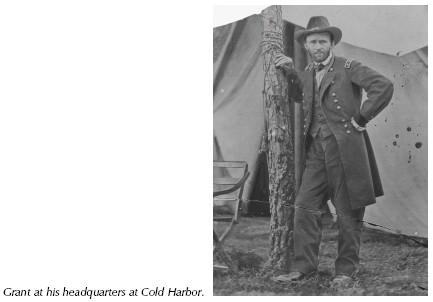

THE BATTLE OF COLD HARBOR

After weighing his options, Grant decided to swing his army to the left yet again. His lead units stepped off just after nightfall on May 26. This time Grant’s target was the crossroads of Cold Harbor, another twenty-five miles or so to the south-southeast of the North Anna battlefield and only about ten from Richmond, on the Gaines’ Mill battlefield, where McClellan and Lee had fought the third of the Seven Days’ Battles almost two years before. Yet again, Lee detected Grant’s move and countered by retreating to meet him. Union and Confederate cavalry sparred with each other repeatedly as they screened and scouted in front of their armies and reached Cold Harbor on the last day of May. The rival horsemen struggled for control of the crossroads, fighting dismounted as cavalry almost always did in this war when combat grew severe. Each side looked eagerly for the arrival of its supporting infantry, the arm of the service that did most of the heavy fighting.

The Confederate foot soldiers were first on the scene, but when on the morning of June 1 the lead division of gray-clad infantry made its bid to drive off the Union cavalry, its attacks were piecemeal and poorly coordinated. The Union troopers, fighting not only dismounted but also entrenched, stood them off until the blue-clad infantry could come up and take over, securing a stalemate around Cold Harbor. By this point in the campaign, although a steady stream of reinforcements hurried on by Richmond had replaced almost all of the troops Lee had lost since fighting had opened in the Wilderness almost four weeks before, the Army of Northern Virginia had nevertheless lost a good deal of its offensive edge, largely because of the attrition among its experienced leaders, from regiment and brigade commanders all the way up to generals commanding corps. Henceforth when Lee tried to take the initiative, he would find his army almost as clumsy a weapon as Grant had found the Army of the Potomac from the campaign’s outset.

Grant sensed the diminished offensive power of Lee’s army and also noticed that even when the Army of the Potomac had occupied a vulnerable position straddling the North Anna, with a corps isolated on either flank, the Confederates had not attacked. He drew the conclusion that the opposing army was on its last legs. “Lee’s army is really whipped. The prisoners we now take show it, and the actions of his Army show it unmistakably. A battle with them outside of entrenchments cannot be had.”

4

With that thought in mind he ordered a quick attack on the evening of June 1, but the commanders of the Union assault divisions had had little time to reconnoiter the enemy’s position or to arrange their own troops. The result was failure. Much as he had at Vicksburg in late May the year before when a similar quick attempt to take advantage of momentum and storm the city had failed, Grant ordered thorough preparation and a full-scale assault. While Grant’s subordinates made their preparations, Lee’s engineers laid out and his soldiers constructed the most elaborate line of fortifications yet seen in Virginia. Meade, to whom Grant had entrusted the task of preparing and reconnoitering for the attack, did not see to it that his subordinates made adequate reconnaissance of the intricate new defenses.

When the time for the big push came at 4:30 a.m., June 3, many Union soldiers were grimly pessimistic about their chances. The army did not yet use dog tags, and whether a casualty’s family would ever be notified of his death usually depended on whether comrades of his own company—and thus usually from his own hometown—found his body and wrote to his loved ones. Now in the faint hope that some other kind soul might perform that last kindness for them, many of the soldiers wrote their names and home addresses on slips of paper and then pinned those slips to the backs of their uniform jackets.

When the attack went in, many units did not press it home with much vigor. Especially in the sectors that had experienced repulse on the evening of June 1, troops went to ground before reaching the prime killing range of the Confederate rifles. Elsewhere along the front, the Federals pushed forward doggedly. In the Second Corps sector they even scored a brief local success, taking a few of the advanced Confederate trenches before Rebel artillery and counterattacking Rebel infantry drove them out. The end result was the same, and when the firing slowed down and the smoke cleared somewhat, it was obvious that the Army of the Potomac had made no dent in Lee’s lines. Grant ordered a halt shortly after noon. The attack had cost the Army of the Potomac somewhere between 3,500 and 4,000 men. For the rest of his life, he regretted having ordered the June 3 assault, as he did the May 22, 1863, assault at Vicksburg, but as Lee too had learned from hard experience, sometimes the only way to know that a major assault would not work was to try one.

Action along the front settled down to desultory sniping and artillery bombardment. On June 5 Grant sent Lee a note by flag of truce suggesting an informal two-hour truce to recover the dead and wounded from between the lines. Lee’s reply insisted that the truce be a formal one, which would, in the military etiquette of the time, amount to a tacit admission by Grant that Lee had defeated him in a major battle—a small propaganda coup and a point of pride for the Confederate general. Grant was naturally reluctant to gratify his enemy in this way or do anything else that might hurt Union morale in what was already becoming a difficult campaign season, with its heavy casualties and lack of the immediate dramatic success that many had unreasonably expected. Yet after some further exchange of stiff notes, he finally concluded that there was no other way to help his wounded men. The formal truce took place on June 7, by which time it was already too late for most of the wounded lying between the lines. Union morale continued to erode both inside the Army of the Potomac and on the home front, where some were already beginning to criticize Grant, little more than a month into his first major campaign as general in chief.

GRANT’S PETERSBURG GAMBIT AND EARLY’S RAID ON WASHINGTON

Grant could see clearly that although the Army of Northern Virginia might have lost some of its previous operational verve on the offensive, it was more than ready and able to fight defensively behind breastworks, and Lee had it firmly positioned so that that was all it needed to do in order to fulfill its primary mission of protecting Richmond. Grant had reached a tight corner from which no further left-handed turning movements could bring the Army of the Potomac closer to the Confederate capital so as to threaten it and force Lee to fight on terms other than his own. After several days’ consideration, Grant determined to undertake a bigger and bolder turning movement than any he had yet made in Virginia. It would not take the Army of the Potomac closer to Richmond but farther away, but in doing so it would pose a still greater threat to the Confederate capital.

Grant’s plan was to break contact with Lee’s army and swing to the left again, cross the James River, and march against the town of Petersburg, Virginia. Located on the Appomattox River about thirty miles south of Richmond, Petersburg was the railroad hub on which depended the food supplies both of Richmond and of Lee’s army. There the Weldon Railroad, coming up from the south, joined the Southside Railroad, angling in from the southwest, and their combined freight rode a single set of rails the final thirty miles north to Richmond. If Grant could take Petersburg, Lee would have to give up Richmond. The movement began on the night of June 12 and ran smoothly. Grant’s army crossed the James River on a 2,100-foot pontoon bridge Union engineers had built. Lee suspected nothing, and his army remained in its entrenchments around Cold Harbor.

The Confederate general too had been thinking during the week that had followed the doomed Union assaults. Despite his army having fared better in the fighting at Cold Harbor, Lee was grim about the long-term prospects. “We must stop this army of Grant’s before he gets to the James River,” he told his subordinate General Jubal Early. “If he gets there it will become a siege, and then it will be a mere matter of time.”

To stop Grant, Lee decided to try a method that had worked against other Union commanders in 1862. He dispatched Early, now in command of the Second Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia in place of Ewell, to march west and enter the Shenandoah Valley. The valley was a natural advantage for the Confederacy. A Confederate army in the valley could relatively easily screen its movements from normal Union cavalry reconnaissance by holding the limited number of passes over the Blue Ridge, on the valley’s eastern edge, and as long as that army was in the valley it could draw its rations from the well-stocked granaries and smokehouses of that rich farming country. The valley slanted from southwest to northeast, so that a Confederate army that marched all the way to its northern end would emerge ninety miles northwest of Washington, well positioned to threaten Baltimore, Harrisburg, or the national capital. Lee hoped that Early’s foray might draw troops away from Grant’s army and put political pressure on Washington to sue for peace.

In 1862 Stonewall Jackson’s operations in the Shenandoah Valley had created alarm in Washington and baited Lincoln into diverting troops from McClellan when that general had been approaching Richmond over the same ground where Grant’s troops had attacked during the first week of June. Lee hoped that Early could launch a raid that would accomplish at least as much. Besides that, Union General David Hunter was operating with a small force in the Shenandoah Valley, and Lee hoped Early would be able to put a stop to that.