This Is Your Brain on Sex (12 page)

Read This Is Your Brain on Sex Online

Authors: Kayt Sukel

Tags: #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology & Cognition, #Human Sexuality, #Neuropsychology, #Science, #General, #Philosophy & Social Aspects, #Life Sciences

To date, much of the data collected about sexual behavior have been conducted by anonymous survey. Though this sort of data can give investigators an idea of the general trends and themes in human sexual behavior, they don’t provide many details. And it is the specifics that we would like to know more about.

To that end, researchers have started to look elsewhere, namely, our evolutionary cousins, the primate species. You see, monkeys do not have the same kind of hang-ups we humans have about sex. They seem to have an implicit understanding of sex as a natural act that occurs without judgment and are indifferent to investigators watching them get it on. They don’t freak out about what their parents, their friends, or the researchers might say if they knew what they were doing, how they were doing it, or who they were doing it with. And they do not appear to worry about avoiding pregnancy, whether their penis is large enough, or whether those five extra pounds will totally turn off a new partner. They pretty much just do it. Refreshing, no?

Researchers interested in sexuality can observe these animals to find out more about the exhibited behaviors. They can also use animal models to look beyond strict behavior and measure things like associated hormone levels and brain activity. This type of study is by no means a perfect comparison to human sexuality, but until we are more willing to open ourselves up for observation, it will have to do.

To learn more about the ways

primates help us understand sexual behavior, particularly sexual motivation, I visited the Yerkes National Primate Research Center to meet with Kim Wallen. I wanted to discover more about what stripping away thoughts of mood, overly sagging scrotums, and general “appropriateness” can help us uncover about human sexual behavior. Wallen, a rugged-looking man with a well-kept salt-and-pepper beard, walked me over to an established group of rhesus macaques to observe what would happen when four new males were introduced to the set. “You’re lucky,” he told me while climbing up to a widow’s walk that would allow us a bird’s-eye view of the enclosure. “This is what amounts to excitement around here.”

Almost immediately Wallen pointed out a brown-and-white female who had confidently plopped herself down in front of a male in the corner of the enclosure. When one of the human attendants got too close, she used her hands to make threatening slaps and gestures toward the fence. “See her hands? She’s actually soliciting the male for sex. She’s using those humans as a foil, threatening as if there’s a real challenge out there,” Wallen explained. “I’ve never completely understood why it works, but females often use aggressive and threatening gestures to others to trigger the male to mate.”

“Maybe to seem more attractive,” I suggested, “to play the damsel in distress and make the male feel like he’s needed.”

The male, a handsome, red-faced gent whom I immediately nicknamed Casanova, did not fall for her ploy. He put his head down and coyly moved it to the side. “That’s a groom solicitation,” said Wallen. “He’s saying ‘I know you’re interested in sex, but I just really want to be groomed.’”

“I just want to cuddle,” I added with a grin. “I’m not a piece of meat.”

The female complied, if not impatiently. She started picking at Casanova’s head, throwing in the occasional signal that she was still up for a good time once he was ready.

“My impression from watching lots of rhesus engaging in sexual behavior is that females are intensely interested in the sex, and males just want to be groomed,” said Wallen. “We tend to think it’s the males out there pursuing the females to try and get them to have sex. In fact the females have to work pretty hard to convince the males.”

The female stopped grooming and once again

showed Casanova her backside. He stared off into the distance, as if he was not getting the rhesus equivalent of a lap dance with a guaranteed happy ending. Once she sat back down, he motioned with his head—another grooming solicitation. I could almost hear the female’s resigned sigh as she turned and resumed grooming, albeit a little less enthusiastically. This dance, female butt-showing for sex and male head-nodding for grooming, happened three more times over the next few minutes. New to this group, Casanova had already mastered the art of playing hard to get.

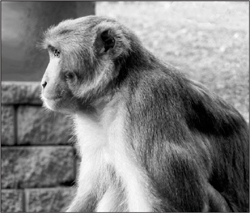

A male rhesus macaque monkey who bears a striking resemblance to my friend Casanova.

Photo by Kim Wallen, Yerkes National Primate Research Center.

In the rhesus culture the females initiate and control sex. They want what they want when they want it. The males, if they want to have sex, are expected to submit to the females’ whims and desires. However, the males aren’t completely powerless in this scenario. They can and do say no. Like my friend Casanova. The new kid in town, he watched the landscape carefully. Given that rhesus colonies are a bit of a female club—Casanova would not be an accepted member of the family until welcomed by females of the group—he knew it was in his best interest to get the lay of the land before agreeing to any hanky-panky.

All of a sudden we heard a scream. A second female, screeching and jumping, scared off Casanova’s first paramour. Once she was sure the competition was gone, she sat herself down in front of him and made her own play for his affections. Casanova looked confused for a moment, then resumed his posture of

disinterest. A slow turn of the head, another grooming solicitation, was the only acknowledgment that Casanova noticed the change of company.

“The notion that the only thing males have on their mind is sex pretty much disappears in this context,” Wallen said with a laugh. New to the group and still figuring out the social structure, Casanova had pretty low testosterone levels. Until he found his place within the community, his hormone levels would remain on the low end. But it was not as if the boy had no testosterone coursing through his body, and one would think that, with several sex options available, his hormones would push him to do the deed even if he was the new kid in town.

Another back presentation by the female, a stronger “groom me” request, and these two monkeys had my unwavering attention. I felt as if I were watching an episode of the old sitcom

Friends

. These two monkeys were having their own Ross and Rachel moment right there in the rhesus compound. Getting impatient, I wondered how many times would this female need to let Casanova know she was interested? How could he just ignore that kind of play for his attention? More to the point, what was it going to take for these two to stop playing games and just do it already? I said as much out loud when I saw one of the other newly introduced males already getting busy in another part of the paddock.

“It really is like watching a soap opera sometimes,” said Wallen, laughing. “There’s a lot at stake here. If he mates with the wrong female and the other females in the group reject him, he’s dead. In the wild he would be forced out of the group. But here the group would harass and attack him to the point of injury.”

The female finally decided she was not interested in playing games anymore. She ignored Casanova’s request for grooming and instead flashed her backside again impatiently. And then again. Then a third time. Casanova simply stared off into the distance, head cocked at a coquettish angle.

“They are in a stand-off now,” said Wallen. “She knows what he wants, but she’s not going to give it to him.” She was ignoring Casanova’s repeated “groom me” requests. She was going to wait it out. Just when I thought she had given up, she solicited him again for sex. Another “groom me” request. I groaned. Who would finally give in? We were at an impasse, and neither Casanova

nor his sweetheart seemed to be interested in making the first move to overcome it.

Then, just as I thought hope was lost, the female caved in and gave Casanova a swift, cursory grooming around his face. The motions took no more than ten to fifteen seconds. If I had not been watching so intently, I might have missed it. Just as quickly, she presented her back to him again. No response from Casanova. Unfazed by all the rejection, she presented again. Casanova stubbornly responded with another grooming request. This little monkey was determined. He was not going to give in, no matter how tempting, until he was good and ready.

“I think the pattern of promiscuity in rhesus may reflect what the pattern of human sexual behavior would be if you removed cultural constraints,” said Wallen. “It’s not hard to take promiscuity and shape it into something that looks like the sort of monogamy we humans have ended up with.” He paused. “Human monogamy is much less strict than we think it is.”

Stubbornly, with obvious irritation, the female presented again. It was as if she were saying, “Okay, buster, last chance. Take me to bed or lose me forever.” Instead of asking to be groomed this time, Casanova simply looked away and started grooming himself. It was the ultimate dismissive gesture: If you aren’t going to groom me, I do not need you. The female stalked off, probably in search of more amenable company.

Casanova was not alone for long. Before I could even comment about his last girlfriend’s abrupt departure, a third female sat down nearby. And this one was a lady; she solicited him very subtly, like a Victorian woman daintily showing her ankles as she took her seat. Casanova again solicited grooming. She acquiesced, but only for a moment. It was easy to see that grooming was not her thing. Lady or no, she was looking for some action. Once again Casanova appeared completely uninterested. I sighed with vexation.

“What do you think of this?” Wallen asked.

“Honestly, I’m wondering what the heck Casanova is waiting for!” Three separate females, all good-looking enough in their rhesus way, had offered him what every male supposedly wants: sex. How dare he turn them all down?

“This is fairly typical,” Wallen explained. “It may take a male and female an hour and a half before they

actually do it. Even then, they may start mating, stop, break apart, and then come back together. It may take an hour or more after mating starts before he actually ejaculates.”

The thought exhausted me. With all these games, even in the rhesus population, how do babies ever get made? But before I could start yelling at Casanova to stop posturing and just hit that already, shrieks erupted below me. Jumping and screeching with menace, a large group of rhesus barreled toward the corner where Casanova and his group of lady friends had been hanging out. They were upset with a different animal, one of the other new males, and massed in force to teach him a lesson. They did not seem to mind if Casanova ended up as collateral damage. Wallen ran down to break up the fight before one of the animals was injured.

When calm was restored, it took me a minute to find Casanova. I soon spotted him hiding under a large climbing structure, scared and alone. No females were approaching now. Once Wallen returned to the widow’s walk, he explained that Casanova abstained from sex for good reason: with the introduction of four males to the group at one time, there were a lot of uncertainties about what the new members would do to the existing social structure. “Now we know why he was so hesitant,” said Wallen. “He was scared out of his wits. It’s really hard to get an erection when you’re petrified that you’re going to get attacked.”

The highest-ranking member of any rhesus group is going to be a male. But it is still a girls’ club with girls’ rules. It is the alpha female who picks the alpha male by mating with him. If he offends her in some way, he can always be replaced. While our eyes were on Casanova, the alpha female was still trying to decide who was worthy of her affections. The monkey under attack was the male who made the faux pas of getting a little something before she had made her choice. The social structure of the group, including its rules, culture, and leadership, had yet to be decided. It was in Casanova’s best interest to wait it out—not only in case the alpha female decided to bestow the ultimate prize on him, but also to make sure he was not inadvertently offending someone who had pull once order had been established. Sex is not the ultimate prize when it can get you thrown out of the group. Despite all those hormones running amok in my friend Casanova, he was able to keep his head and think about the consequences.

Even a monkey has the power to overcome his hormones.

Society’s Pull on Our Hormones

Now that the Casanova Show was over, Wallen and I made our way to a different area of the field station, where one of his graduate students, Shannon Stephens, was observing a smaller group of rhesus monkeys. In this tighter enclosure the animals could run and frolic, seemingly oblivious to us as we watched from above. To my untrained eye these monkeys looked no different from the ones Wallen and I had watched earlier. But a few of them, with dyed patterns on their backs, had brains that were significantly unlike the others’.

Shannon was studying behavioral differences in these animals after neonatal amygdalectomy, a surgical procedure that extracted their amygdala after birth. In particular she and Wallen were interested in whether the removal of this almond-shaped brain region responsible for emotional memory would affect the onset of puberty in young females.