This Is Your Brain on Sex (15 page)

Read This Is Your Brain on Sex Online

Authors: Kayt Sukel

Tags: #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology & Cognition, #Human Sexuality, #Neuropsychology, #Science, #General, #Philosophy & Social Aspects, #Life Sciences

Zeki and Romaya found similar patterns of brain activation and deactivation across all participants,

replicating the findings from Zeki’s original romantic love study. Once again measurements of cerebral blood flow support the idea that love is both rewarding and blind. But there were no significant differences between activation patterns in men and women. Considering the sexual dimorphism seen in many parts of the brain, it’s an intriguing result. It appears that love is love, no matter what gender you are.

When I asked Zeki if he was surprised by the finding, he chuckled. “To be honest, I was entirely agnostic,” he said. “I cannot say I was surprised by the results. But I think this is one of these studies where people would have said, ‘I’m not surprised,’ even if the results had gone the other way.”

So Are Men and Women Different or Not?

It is easy to fall back on old stereotypes, to simply say that men and women are poles apart. And perhaps those differences are enough to fuel those storms you commonly see in relationships. It would almost be easier if we could say that male and female brains are just too dissimilar, that they perceive and process love and sexual stimuli separately; it would give us something to hold on to when no other explanation for our love-related woes seems available. Alas, it is not quite so simple.

“When we talk about sex differences in the brain, people want to go all ‘Mars, Venus’ on you. They want to take these results and try to spread males and females way apart on function and ability,” said Cahill. “It is not like that. When you are talking about sex influences on brain function, you may have two bell curves that are significantly different from one another in certain instances. But those bell curves are still overlapping.”

Goldstein concurred. “There is more variability within a given sex than between sexes in cognitive behavior and the brain. That is important. In fact, I always say it twice so that people really understand that,” she said. “There is more variability observed between women than between women and men in both the size of different brain regions as well as the function.”

Meston saw the same kinds of overlapping

bell curves in her research. “Every person brings their own individual history to any sexual situation,” she said. “The reasons why they are having sex, the way they feel about the sex, and the consequences of having sex are all very different across individuals no matter what gender they happen to be.”

That’s something to consider the next time you want to chalk up your partner’s quirks and shortcomings to his or her gender alone.

Chapter 7

The Neurobiology of Attraction

What is it that attracts us to another per

son? When I asked my friends what initially drew them to their significant other, the responses varied from “his gorgeous blue eyes,” to “her honesty and intelligence” to “He had air-conditioning—we met in Niger in summer.” I also heard quite a few comments about beautiful smiles and nice butts, from both sides of the gender divide, as well as tributes to cute dogs, cable sports packages, passion for a career, motorcycles, crack handyman skills, attractive friends, and even sweet, sweet pity. The responses truly ran the gamut. When I consider my own experience, I can honestly say I’ve been attracted by many things. I dated one man who had a laugh that immediately put me at ease, another whose brilliance placed him at the top of his field. And I see no reason not to mention that I’ve gone out with a guy or two for no other reason than they were drop-dead gorgeous.

Although many of us can point out the one thing that initially sparked our interest, it is never quite that straightforward. Simply stated, there is no

one

thing. No matter how nice a woman’s derriere looks or how hot a Niger summer gets, any attraction is made up of a variety of elements, physical, mental, and emotional—perhaps even physiological. Other types of comments made by friends mentioned butterflies in the stomach, a feeling of being drawn to the person as if by “tractor beam,” and “just knowing” this person was meant for them. A couple of friends even admitted that the basis of their attraction was a mystery: they weren’t certain what exactly drew them to the person,

only that it was undeniable at the time. This is a case where the whole is much, much more than the sum of its parts.

“Obviously, there’s a lot to attractiveness,” said Thomas James, a neuroscientist at Indiana University who studies sexual decision making. “There’s his face, and that’s important. But you want to see your guy get up there and dance, see how he moves. You want to hear his voice. He may have a great face, but if it’s paired with a squeaky high voice, there goes the attraction. If he has an okay voice, what he actually has to say plays an enormous part. There’s a lot to it.”

“You can’t forget smell,” I added. “Smell is important too.” I’ve been overpowered by cheap cologne far too many times not to mention it.

“Right. So we are beyond the visual here. We have the auditory, the olfactory, how the guy moves, what he says—and we’re only getting started,” said James. “There’s so much there. It’s a real challenge to try to capture those variables in an experimental way.”

And the challenge only seems more immense when you try to examine it from a neurobiological perspective. What is it that we are picking up from another person that forces our attention so strongly upon him or her? That can sexually arouse us after only a look or a word? Make us crave that person’s future company? After attraction has been established, what is it that determines whether it will grow into love? Does that attraction have to be there immediately, or can it grow over time? It’s hard to know which question to address first.

Here’s a case where animal models are not much help. Female rats don’t care if a male rat has a sense of humor or what he does for a living. It doesn’t matter to male rats how many baby daddies a female has previously entertained or whether she has a season pass to Penn State games. I don’t even know how to begin to qualify what might count as hot on the rat ass scale, but I do know that a show of teeth in these critters usually precedes an attack. Courtship in rodents and human beings is not all that analogous.

For example, the prairie vole, the rodent mascot of love, becomes attracted to another vole after a lot of urine sniffing. The pheromones, small chemosensory compounds, in the urine give these animals enough information to help make a connection

and get to work getting busy. The same setup is not going to work with humans. Though I made sure to mention smell when I talked about attraction with Thomas James, I’ve never taken it so far as to smell a guy’s pee.

That’s not to say that different scents don’t have some influence in the human brain. Wen Zhou and Denise Chen, researchers at Rice University, found that human sweat during sexual arousal selectively activates different areas of the brain. The duo had male sweat donors abstain from using deodorant, antiperspirant, and scented body care products before coming to the lab to watch twenty minutes of heterosexual porn and then a neutral video of the same length. The men did their watching with absorbent pads under each armpit that collected the sweat associated with each viewing condition. The researchers then pooled the sweat from all the participants after they watched the sexy video and did the same for the neutral viewing condition to create the study’s two olfactory stimuli (that’s science talk for a sample of something participants would smell during the study).

Using fMRI Zhou and Chen scanned nineteen women who had sniffed the combined products of the porn and neutral video viewing sessions. They also measured cerebral blood flow after the participants smelled a putative sex hormone called androstadienone, a metabolite of testosterone that has been linked to elevated mood and cognition in women, and a nonsocial control smell. The study participants inhaled each compound for twelve seconds, then rated the pleasantness of each smell on a scale of 1 to 5. Note that these women were not told what the smells were, or even that they were human in origin. They were simply told to take a good whiff and determine how much they liked it.

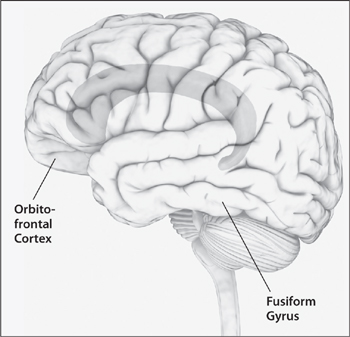

The researchers found that the human sexual arousal sweat showed a distinct activation pattern in the right orbitofrontal cortex, an area related to socioemotional regulation and behavior, and in the right fusiform region, an area usually implicated specifically in human face and body perception. The group also saw activation in the right hypothalamus, the seat of sexual behavior, from the sexual arousal sweat but none from the control smell.

1

Zhou and Chen found activation in the orbitofrontal cortex and fusiform gyrus when study participants smelled human arousal sweat. The hypothalamus was also activated.

Illustration by Dorling Kindersley.

This means our brain is doing

a lot with the chemosensory information in the sweat of sexual arousal. Somehow we know that it belongs to another human without being explicitly told so. Our brain also seems to understand that the scent has something to do with sex. These smells are managing to convey a lot of important information without our even being aware of it.

Given that we humans do not have a solid understanding of all that goes into attraction, and the assumption that evolution wouldn’t throw away a system that works for the majority of the animal kingdom, some neuroscientists have suggested that chemosensory cues play a role in our attractions. Perhaps along with (or even instead of) bright smiles and intelligent conversation, a person’s smell lets us know if he or she is worth spending time with. Certainly more than a few fragrance companies and Internet outfits believe this—human “pheromones” have long been advertised as a sure thing for attracting members of the opposite sex. Though some contend there’s no such thing as a human pheromone, Zhou and Chen’s study suggests that our brains are picking up something from social smells.

What Is a Pheromone?

Nearly 150 years ago Charles Darwin

pointed out that being smelly—you know, in the right way—could help male ducks, elephants, and goats procure a mate. It was not all pretty feathers or a strong trumpeting cry. Rather, in

The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex

Darwin argued that chemical signals are just as important as visual or auditory ones when it comes to animal attraction.

2

As the old Cole Porter ditty goes: “Birds do it, bees do it, even educated fleas do it”—except that rather than falling in love, they release a variety of chemical signals through their skin and waste products that cue members of the opposite sex to come calling. Those chemical signals would be the pheromones.

Originally defined by Peter Karlson and Martin Lüscher in 1959, a pheromone (from the Greek

pherein,

“to transfer,” and

hormōn,

“to excite”) is a small chemical molecule that helps an animal communicate with other animals within its species. I know that seems vague. You may be asking, “Communicate what, exactly?” The answer is “many things.” Though the word

pheromone

is often used as a synonym for a sexual attractant, that’s a bit of misnomer. There are several types of pheromones that have been identified in the animal kingdom: primers, releasers, modulators, and signalers.

Primer pheromones are just that: primers that act on the body’s neuroendocrine system and jump-start different functions, such as menarche and puberty. Releasers provide the sexual attractant variety of pheromones, eliciting a behavioral response such as lordosis in females, the arched-back ready position for sex. They can also be alarm signals, motivating certain animal species to withdraw from dangerous situations or gear up for a throw-down. Modulators can change emotions; they are chemicals released by the body that can positively affect mood and emotional state. And signalers are compounds that provide information about gender, reproductive status, and age. Our bodies, it seems, don’t keep many secrets. They are releasing little chemical bits of information at any given moment for others to unconsciously pick up. Those little bits may then alter the internal body chemistry or help an individual intuitively size up social situations.

3