This Is Your Brain on Sex (17 page)

Read This Is Your Brain on Sex Online

Authors: Kayt Sukel

Tags: #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology & Cognition, #Human Sexuality, #Neuropsychology, #Science, #General, #Philosophy & Social Aspects, #Life Sciences

In a more recent study Savic and her colleagues tested anosmic men, or those who could not smell due to nasal polyps, and normal controls, using a paradigm similar to her first pheromone study. As expected, the men who were unable to smell did not show the EST activation. Savic believes this proves that the olfactory system is necessary and sufficient to process pheromone-like signals in humans.

9

Savic’s work remains controversial. The levels of pheromones that she uses in her studies are orders of magnitude higher than what you’d find in your average human. That high concentration, many argue, nullifies the results. “These are levels one thousand times more concentrated than what you’d find on the human body,” said Wysocki. “If this is supposed to be a human pheromone

, you’d expect the same effects at levels found on the human body or even below that level.”

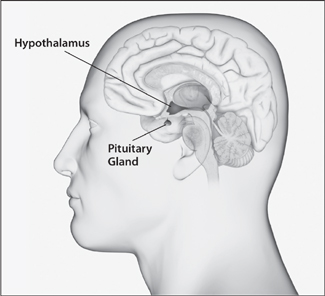

The hypothalamus is activated when humans smell animal pheromones.

Illustration by Dorling Kindersley.

Savic acknowledged that the levels used in her experiments may not be the same levels seen in nature, but she argued that her work was still worth further study. Based on her findings, she believes that humans are susceptible to pheromone-like signaling and that future studies will support her hypothesis. But when I asked her about how important they may be to attraction, she paused. “We have not looked at attraction, we have just found these compounds can make physiological changes to the brain,” she said. “It is clear that there are ordinary odors we don’t consciously perceive targeting specific regions of the brain. That’s very compelling and provocative. But there is much more to learn.”

“So could attraction be all about pheromones?” I asked.

“No, not at all.” She laughed. “Attraction is complex, there are so many factors. Pheromones may be one of those factors. If they are, there are inhibitory connections from other parts of the brain that can augment what those particular odors may do in the brain. But we don’t know. It hasn’t been properly tested yet.”

That’s something to consider before you pick up your own can of Boarmate and spray yourself (or your cat) with it.

I Feel the Need for Speed

There is almost nothing more frightening

than reentering the dating world as a woman in your midthirties. Trust me on this. Back in the late 1980s, when I started going out with boys, my biggest concern was convincing my mom to drive me to the movie theater without asking too many questions. In a certain sense, not much has changed. Today I still have to deal with my mom, although now I just have to convince her to babysit without asking too many questions. It pains me to admit it, but I am still a bit clueless. Though some would argue that my age makes me a better candidate for the dating pool (if only by appropriately pruning my expectations), I can’t help but feel differently.

My friends are pushing me to get back out there, one way or another. One friend, a single dad and busy professional, says speed dating is the way to go. This new paradigm is increasing in popularity, mainly because you don’t have to invest all that much time and you are guaranteed to meet more than a dozen “dates” in one evening. Each event involves about twenty women, twenty men, and a good stopwatch. Each singleton spends about four to eight minutes (depending on the event coordinating company), one on one, with each member of the opposite sex. At the end of the evening speed daters have to make a simple decision about each person they met: Would you like to see him or her again? If both the speed dater and his or her persons of interest answer in the affirmative, the event coordinators will send both the corresponding contact information. My friend is a big fan of the setup. He highly recommends it as a fun (but mainly efficient) way of meeting potential dates. Apparently it gets him laid a lot. As it turns out, speed dating is also offering researchers more information about attraction.

In 2004 Eli Finkel, a professor at Northwestern University, took students from a graduate seminar on close relationships, including Paul Eastwick (now a professor at Texas A&M University) on a speed dating field trip. It was a bit of a lark. However, after experiencing it for themselves, Finkel and Eastwick thought it made

a good paradigm for study; they were surprised at how much information they took away from only a few minutes of meeting with a potential date. Maybe, they thought, speed dating would provide new insight into what attracts us to other people.

Attraction, like love, has gotten short shrift in the research world, and for the same reasons: it is a complex thing that is hard to define or systematically study. Social psychological research from the 1970s did some looking into the matter. Common wisdom, such as that men appreciate physical attraction more than women and that women are most attracted to a good earner, hail from these studies. Did those results cover the full extent of it? Given the variety of responses I had from just a small group of friends about what they found attractive about their mates, I’d think not.

Finkel and Eastwick wondered the same thing. So the two started holding their own speed dating events, experimental paradigms where members of the opposite sex would meet for four minutes, then judge whether they’d like to meet up with any of their “dates” later. Here, however, each meeting was video-recorded, to be coded for specific behaviors by trained observers later, and all participants received follow-up surveys months after attending.

One of the pair’s first findings was a bit of a surprise: that what we think we want in a partner is not usually what we go after. Finkel and Eastwick had a group of speed dating participants fill out a questionnaire about what they were looking for in a partner. In these surveys the old adage that men appreciate physical beauty and women appreciate earning potential held up. However, when those same individuals met dates face-to-face, the ideals were not as important. Rather, both men and women were drawn first to physical attractiveness and then to personality, followed by earning potential. In a real-world situation (or as close as you can get in an experiment), those attraction sex differences we’ve so long held as universal truths disappeared.

10

Physical attraction trumped all, whether you carried two X chromosomes or an X and a Y.

In an interview with

Newsweek

magazine, Finkel offered this advice to daters based on his study: “Beware the shopping list. When you go into finding a romantic partner, don

’t have this list of necessary characteristics that you need. Go in with an open mind. Actually meet people face to face. Because you might find yourself surprised by the person you’re attracted to.”

11

There’s something to be said for that. I’ve certainly been attracted to a lot of “surprises” over the course of my own dating career. Many I discounted because they did not match my idea of an ideal partner. It makes me wonder if I wasn’t a bit too hasty in deciding they weren’t for me.

Attraction is not all about good looks; a pleasant conversation is important too. To test the idea, Finkel, Eastwick, and their colleagues looked at language-style matching, or how much individuals matched their conversation to that of their partner orally or in writing, and how it related to attraction. This verbal coordination is something we unconsciously do, at least a little bit, with anyone we speak to, but the researchers wondered if a high level of synchrony might offer clues about what types of people individuals would want to see again.

In an initial study the researchers analyzed forty speed dates for language use. They found that the more similar the two daters’ language was, the more likely it was that they would want to meet up again. So far, so good. But might that language-style matching also help predict whether a date or two will progress to a committed relationship? To find out, the researchers analyzed instant messages from committed couples who chatted daily, and compared the level of language-style matching with relationship stability measures gathered using a standardized questionnaire. Three months later the researchers checked back to see if those couples were still together and had them fill out another questionnaire.

The group found that language-style matching was also predictive of relationship stability. People in relationships with high levels of language-style matching were almost twice as likely to still be together when the researchers followed up with them three months later.

12

Apparently conversation, or at least the ability to sync up and get on the same page, mattered.

Granted, these results offer somewhat of a chicken-and-egg problem. Are the couples well suited to each other because they share similar conversational styles? Or do they develop similar conversational styles because they are well

suited to each other? It’s hard to say. But the researchers believe this is yet another key variable to understanding interpersonal relationships.

Based on the success of Finkel and Eastwick’s studies, Jeff Cooper, a postdoctoral fellow formerly of Trinity University in Dublin and now at California Institute of Technology, decided to use speed dating to look at the rewarding aspects of interpersonal attraction. But he tweaked the paradigm a bit so he might be able to add a neuroimaging component. After all, if Helen Fisher’s theory is correct and finding a partner is one of the greatest rewards of all, you would expect to see the reward areas of the brain light up when you meet a potential candidate. Certainly Cooper thought it should be so. “We know, behaviorally, there is reinforcement value in your perception of how others think of you,” he told me. “But it’s a hard thing to study, especially with neuroimaging. Social rewards activate the brain’s reward networks, we know that. But we wondered if interpersonal attraction, the feeling that someone else likes you, would map in the same way.”

Cooper and his colleagues ran six speed dating events and then had participants come to the lab a day or two later to participate in the fMRI portion of the study. There participants were scanned as they viewed a photo of a person they had met followed by that person’s yes or no decision about wanting to meet up again. Immediately after that, participants were asked to rate their happiness or unhappiness with the other person’s decision about getting together again.

In a preliminary analysis, the group found strong reward system activation—but only when participants received a “yes” response from a person they had also said “yes” to. That correlated with participants’ happiness ratings about the other person’s decisions. At first glance, these data indicate that a person’s liking you is rewarding, but only if you like him or her back.

Cooper and his colleagues wondered if the anticipation of someone else’s decision might also affect the brain. So they took a look at the brain activation when the study participants viewed the photo

before

seeing whether or not the person wanted to get together again. Again the preliminary analysis showed the reward areas of the brain lighting up like fireworks. Cooper’s explanation is that when you like someone enough to give him or her

a “yes,” you will then anticipate that person’s response to you. In the speed dating scenario, it would seem, the reward system activation is active not just for receiving rewards, but also for anticipating them. But getting a “yes” was significantly rewarding only if there was some mutual appreciation going on; otherwise the reward system stayed relatively quiet. “Getting a yes, in other words, varies enormously in reward value depending on how you feel about the person you got it from,” said Cooper.

13

This work is new and ongoing. The researchers plan to do future studies where they scan individuals before a speed dating event. Perhaps there is something in a photo alone that may indicate whether or not you’ll end up wanting to go out with another person. Given that physical attractiveness—for both sexes—is a key variable in interpersonal attraction, a picture may be worth more than a thousand words in this scenario. Once the researchers thoroughly analyze all of the data and move on to more complex studies, it’s likely they will discover quite a few interesting quirks about what our brains find rewarding when a new person captures our attention. After all, to steal the Facebook line, when it comes to attraction and relationships, it’s complicated.

The Take-Home Message

No matter where you look, you can find all manner of advice about how to attract a mate. Magazine covers, dating services, advertisements, fragrance companies—they all want to make us believe there is some key to finding the right person, and they even offer that one special product or service that will help us. The science, however, says it’s not quite that simple. There is no attraction smoking gun, whether we are talking about pheromones or a person’s earning potential. The only element that repeatedly qualifies as important is physical attraction. That’s not such a surprise—but it’s a phenomenon that is difficult to study empirically.