To Hell on a Fast Horse (26 page)

Read To Hell on a Fast Horse Online

Authors: Mark Lee Gardner

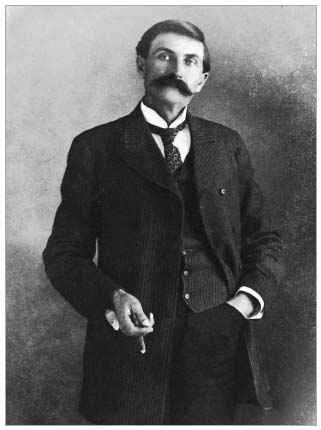

Pat Garrett as collector of customs, El Paso, circa 1903.

University of Texas at El Paso Library, Special Collections Department

Other complaints revolved around Garrett’s alleged lack of “tact and common politeness” in performing his duties. It is easy to imagine the fifty-three-year-old Garrett, who was once

the

law in New Mexico, exhibiting a decided lack of patience, even a short temper, with anyone who attempted to get around their customs duties, sought some personal favor, or simply argued with him about a decision. The Treasury secretary reprimanded Garrett via letter, essentially ordering him to be more polite. Garrett was outraged. But he received an even harsher rebuke from the secretary after he got into a fistfight with a former customhouse employee, George M. Gaither. Garrett had been forced to accept Gaither as a temporary inspector because of the criticism over Garrett’s cattle appraisals, a sore point with the collector. Gaither’s appointment was for a thirty-day trial period, and Garrett had no intention of keeping the man at the customhouse a single minute after the trial period expired. But after Gaither was dismissed, he went about El Paso claiming that Garrett had reneged on a promise of a full-time job. When Garrett ran into Gaither on the street, he called the man a goddamned liar—Garrett hated liars—and that was when the fistfight broke out. This made the papers as well, but Garrett still held on to his collectorship.

What many believed finally cost Garrett his job occurred in San Antonio in April 1905. President Roosevelt was visiting the home of the Alamo for a reunion of his famed regiment of Rough Riders. He had

invited Garrett to join him there and to sit at his table at an outdoor lunch planned for the Rough Riders. But Garrett brought along as a guest his good friend Tom Powers, the owner of a saloon and gambling establishment called The Coney Island, which was Garrett’s favorite watering hole in El Paso. Garrett even arranged to have a photograph taken of himself and Powers with the president. But Garrett did not tell the president anything regarding Powers’s well-known reputation as a professional gambler, and when Roosevelt found out later, he was extremely upset. Eight months later, as Garrett’s four-year term as collector was coming to an end, he learned that Roosevelt had decided not to reappoint him.

Roosevelt told Garrett and others that the Powers incident had not had anything to do with his decision, but there is no question that it put an end to Garrett’s political career. First, the Texas Republicans had never forgiven Roosevelt’s administration for not giving the collectorship to a Texan. Then there was the icy relationship between Garrett and the Treasury secretary. The secretary told the president that Garrett had been an inefficient collector, and that he had heard reports from El Paso that Garrett was often absent from his post, was in debt, and had not curbed his gambling and drinking. Last, Roosevelt had not fared well in the press for handing government appointments to men with what were perceived to be notorious pasts. His appointment of Bat Masterson as a deputy U.S. marshal for New York had prompted the

New York Evening World

to write, “The President likes killers.”

As soon as Garrett realized his job was in jeopardy, he rushed to Washington to plead his case with Roosevelt. Against the advice of friends, Garrett insisted on taking Tom Powers with him. Powers had considerable influence in El Paso, and he somehow believed he could help his friend with the president. But Roosevelt would not see Powers, though Garrett stuck up for his friend, telling the president that he would gladly introduce Powers to anyone. Even so, it quickly became

clear to Garrett that the president had already made up his mind. The

Washington Post

noted that Garrett looked dejected after visiting the White House and in other ways exhibited “the bitterness of defeat.” In a last-ditch effort, Garrett’s writer friend Emerson Hough wrote a letter, pleading with Roosevelt, even promising that Garrett’s resignation would be on the president’s desk no later than July 1, 1906. This six-month reprieve would allow Garrett to maintain his pride and say he left the job himself. By the time Hough wrote his letter, Roosevelt had appointed a Texas Republican to take Garrett’s place.

Garrett with President Theodore Roosevelt at the San Antonio Rough Riders reunion, 1905. Tom Powers is the man in the Stetson, second from the right.

University of Texas at El Paso Library, Special Collections Department

When he returned to Texas, Garrett answered a few questions from a Fort Worth reporter about his future prospects. “I have a ranch in New Mexico,” he said. “And I will go there for a time. Just what my future plans will be I do not know. However, I am going to do some

thing and don’t expect to remain idle. I have no complaint to make against anyone for my removal. I simply take my medicine.”

GARRETT HAD LITTLE TIME

to dwell on this. By January 1, 1906, he was in Santa Rosalía (present-day Camargo), Chihuahua, Mexico, investigating a brutal slaying involving an American rancher named O. E. Finstad. The Mexican authorities believed that Finstad had murdered his brother-in-law and another man; Finstad said they were attacked by “assassins.” Garrett, who was licensed to practice law in Mexico, had been employed by either Finstad or, more likely, Mrs. Finstad to help with the defense. The Finstads no doubt believed that Garrett’s notoriety as a lawman would bring attention to their case, and it did. Garrett conducted his own investigation and determined that Finstad and his associates were assaulted by Mexican bandits. He then appealed directly to President Roosevelt, asking for the American government’s assistance in the case. But despite Garrett’s efforts, which were substantial, the Mexican court convicted Finstad in early March and sentenced the rancher to twelve years in the penitentiary. It was Garrett’s one and only Mexican legal case.

Garrett was always looking for the big “trade,” the deal that would make him thousands of dollars all at once. The Finstad case had simply represented some quick cash, but while Garrett was in Mexico, he thought he found the next moneymaker: a silver mine in Chihuahua. Garrett wrote Emerson Hough in Chicago that the property could be acquired for $50,000 in cash and $50,000 in stocks. If Hough could interest some of his friends, Garrett believed they would all make a handsome profit. But Garrett had not had the best of luck with earlier mining speculations in New Mexico, and it is unlikely that he was able to convince Hough or his Chicago associates. And like most of Garrett’s friends, Hough knew the ex-lawman was in debt—to just about everyone.

Some of Garrett’s debts had been outstanding for years, and instead of using the income from his El Paso collectorship to pay down his creditors, he had used it to speculate, gamble, and, incredibly enough, help out any friends who were a little short. When Thomas B. Catron sent an outstanding Garrett note to El Paso for collection, three banks refused it. They had plenty of their own notes against him.

“He might pay for politics or for some other reason of that kind,” Catron was advised, “but he pays no one down here. He figures in lots of deals, but do not think he puts up a cent in any of them.”

Just a few days after Garrett wrote to Hough about the Chihuahua mining scheme, the Doña Ana County sheriff seized all of Garrett’s property, including the family home on his Black Mountain ranch (near San Augustin Pass), so that it could be offered at public auction. This was the result of a long-running legal tussle with an Albuquerque bank over a debt Garrett had incurred sixteen years earlier when he cosigned a $1,000 promissory note for George Curry. In the end, Garrett retained some control of his land, not because he paid up, but because he had already mortgaged most of it, and his “homestead” was protected by New Mexico statute. The livestock he had not mortgaged or snuck off his property was sold to pay his back taxes.

Louis B. Bentley, who owned a store in Organ, kept a small, leather-bound book upon which he had scratched the words

Dead Beats.

The book contained the names Pat Garrett and two of his children, Poe and Annie; Garrett owed Bentley $35.30. In Las Cruces, Garrett had also stopped paying his bill at the May Brothers Grocery, although he continued to buy his foodstuffs there. When Albert Fall learned about the situation and asked the grocers why they did not demand payment, they said they did not want any trouble and were afraid to cut Garrett off. In a remarkable gesture, Fall decided it was not right for the grocers to suffer this debt, and he and another man shared the cost of Garrett’s groceries. Fall truly felt sorry for Garrett, an extremely proud man who was fast becoming a penniless has-been.

“I don’t know how you are fixed,” Fall wrote to Garrett in December 1906, “but suppose you are broke as usual, so I enclose a check for fifty dollars which amount you can return to me if your stock, which I have turned over to the Bank, goes to par or above.”

A couple of weeks later, Garrett wrote Fall: “I have got into a fix where it seems impossible for me to get along without using the $50 I was to send to you…. Be patient with me and I will try and never do wrong again.”

But things suddenly looked up for Garrett when Roosevelt announced in April 1907 that he was appointing George Curry the next governor of New Mexico Territory. Rumors floated about Las Cruces that Curry would make Garrett the superintendent of the territorial penitentiary at Santa Fe. An excited Garrett wrote to Polinaria from El Paso, asking her to send him his dress suit and Prince Albert coat. Not only was Garrett going to attend Curry’s inauguration in Santa Fe, but Curry had invited Garrett to go to Washington with him. “He will do anything he can for me,” Garrett wrote about Curry. “I am going to try hard to do something and feel very much encouraged.” But Garrett was doomed for another disappointment. Curry did not come through with the prison appointment, nor did he really do anything to assist Garrett in a substantial way—odd considering that Curry was partly, if not entirely, responsible for Garrett’s trouble with the Albuquerque bank.

By the end of August, Garrett had begun another business scheme. The

Rio Grande Republican

announced that he had become a partner in an El Paso real estate firm. How Garrett insinuated himself into this partnership is unknown, but it gave him yet another reason to make frequent visits to the border town. During Garrett’s entire term as collector of customs, he had kept his family in New Mexico, and they remained there still, either at a house in Las Cruces or at the Black Mountain ranch. For extended periods, Polinaria was left alone to take care of their children, of whom the youngest, Jarvis, was just

two years old. Garrett’s favorite El Paso hangout was Powers’s Coney Island saloon, where he was known to frequently buy a round of drinks for the house. Just as well known, it seems, was that Garrett spent his nights with a prostitute while in El Paso, a woman remembered only as Mrs. Brown. Emerson Hough may have been referring to this relationship when he wrote to President Roosevelt in December 1905, and said he knew of “only one sort of indiscretion of which Garrett has been guilty. This has nothing to do with his integrity. Would rather not state this but can do so if necessary.”

There is no question that Pat Garrett deeply loved his wife, Polinaria, and his children—his numerous letters to his family reveal a man who was devoted, doting, and, more often than not, worried—but Garrett also led another life away from his family, and that other life drained his already shattered finances and compounded his rapidly deteriorating mental state.

AS WINTER SET IN

and, little by little, the days became shorter and cooler, Garrett became more bitter, angry, desperate, and depressed. Earlier in the year, he had written Hough that “Everything seems to go wrong with me.” By February 1908, the thing most wrong in Garrett’s mind involved a young cowpoke named Wayne Brazel. Born Jesse Wayne Brazel in December 1876, Brazel had gone to work at Cox’s San Augustin Spring ranch at age fourteen, and it was said that Bill Cox treated the boy like a son. He grew up to be a big, good-natured, albeit slow, cowhand, who did not have an enemy in the world. He did not even carry a gun. Albert B. Fall employed Brazel to take care of his horses at his ranch, just east of the Garrett place. More often than not, though, Brazel was looking after Fall’s children, who adored the young man. On days when the weather forced everyone inside, they sat at his knee while he spun some wild tale to their immense delight. He taught one of the little Fall girls to say,

“By-golly-gosh-darn-double-duce-damn,” explaining that that simple line of cussing was all one needed to get through life. Remembering back years later, Fall’s daughter, Alexina, thought Brazel was a little feebleminded.