To Hell on a Fast Horse (29 page)

Read To Hell on a Fast Horse Online

Authors: Mark Lee Gardner

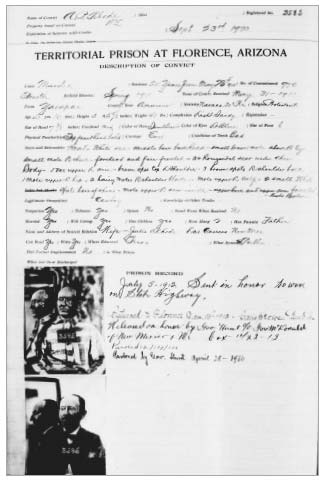

Arrested for murder, Rhode was transported to Prescott, where he received telegrams from Bill Cox and Oliver Lee offering financial aid and legal assistance. But no amount of money and legal firepower could save Print Rhode from justice this time. In May 1911, a jury convicted him of murder, and he entered the territorial prison at Florence as prisoner number 3585 with a twenty-year sentence. Even though Bill Cox was unable to help his brother-in-law in the courtroom, his influence in political circles was another matter. On December 23, 1913, Arizona’s Progressive governor, George W. P. Hunt, released Rhode “on honor” to New Mexico’s governor and Cox. Rhode received a parole a year later and a full pardon on April 28, 1916.

In San Elizario, Texas, a quiet town on the Rio Grande just a few miles southeast of El Paso, Print Rhode died peacefully in his home on October 14, 1942. There was no deathbed confession—at least not one that we know of.

Pat Garrett’s killer took his secret to his grave.

Print Rhode’s Arizona prison record.

Pinal County Historical Museum

Fame is a food that dead men eat.

—

AUSTIN DOBSON

I

N OCTOBER

1905,

PAT

Garrett visited old Fort Sumner with Emerson Hough. Garrett had agreed to help Hough with a book to be titled

The Story of the Outlaw,

and they had an understanding that Garrett would receive a share of the royalties. Sumner was no longer the place Garrett had known in 1881. Its adobe buildings had been torn down some years back, and the large parade ground was a mess of weeds and sagebrush. After some searching, Garrett located the ruins of Pete Maxwell’s residence, and he started taking Hough through the events of July 14—twenty-four years earlier.

“It was a glorious moonlight night,” Garrett began. “I can remember it perfectly well.”

As Garrett told the story of how he killed Billy the Kid, Hough listened in awe, keenly aware of his great fortune in being in the famed lawman’s presence at the very place where justice had finally caught up with the Kid, where a snap shot in the dark had given birth to a legend.

The friends next drove their buckboard to the barbed-wire-enclosed cemetery, which also seemed to be falling down. The Kid’s crude wooden marker had disappeared long ago, and Garrett spent some time kicking around the greasewood and cactus, trying to figure out where the grave was. He finally found it, and he stared down at the ground for a few moments in silence. Garrett then walked to the buckboard, dug out a canteen, and opened it.

“Well, here’s to the boys, anyway,” Garrett said, quietly. “If there is any other life, I hope they’ll make better use of it than they did of the one I put them out of.”

There was another life, of course, a robust mythic afterlife. By the 1930s, Billy the Kid had become a gold mine. Over the previous fifty years, his story had been revisited in the occasional newspaper article and magazine feature, but he officially achieved pop culture status with the 1926 publication of Walter Noble Burns’s

The Saga of Billy the Kid

. Burns’s book was just that, an enthralling, if not entirely accurate, full-blooded tale partially told by the participants themselves—Burns had interviewed several key Lincoln County old-timers about the Kid, the Lincoln County War, and Pat Garrett. Somewhat surprisingly, Burns saw Garrett as a heroic figure, the “last great sheriff of the old frontier,” a characterization that drew criticism from the book reviewer for the

New York Times

. Like the typical Kid lover and Garrett hater—one always equals the other, it seems—the reviewer criticized the sheriff for shooting Billy in the dark “without giving him a chance to fight for his life.” Be that as it may, Burns’s book was a tremendous bestseller. Its success prompted New York trade publisher Macmillan to issue a new edition of Garrett’s rare

The Authentic Life of Billy, the Kid

(Uncle Ash would have been pleased). And in 1930, Burns’s book was the basis of the film

Billy the Kid,

directed by King Vidor and starring Johnny Mack Brown as the title character.

As the Great Depression wore on, the American public embraced

Billy the Kid, the young outlaw-hero who defied authority, just as they embraced the thrilling exploits of modern-day bank robbers John Dillinger, Pretty Boy Floyd, and Bonnie and Clyde. Some of those 1930s “public enemies” found Billy’s story irresistible as well, perhaps even inspirational. After Bonnie and Clyde were shot to death in a horrific ambush on May 23, 1934, a book was found, among other things, resting in the backseat of their blood-spattered car—

The Saga of Billy the Kid

. Everyone fell in love with the myth, the legend, and that myth got another boost in October 1938, with the premiere of composer Aaron Copland’s

Billy the Kid,

which featured a dancing, dudish Billy with iconic black-and-white-striped trousers. The ballet, its score overflowing with traditional cowboy songs, received glowing reviews, including one from Copland’s proud mother, who told the composer that his piano lessons as a child had finally paid off.

By 1938, Billy’s grave at old Fort Sumner (which had received a large tombstone six years previous) was getting hundreds of visitors annually, an impressive figure considering that Fort Sumner was not the easiest place to get to via automobile in Depression-era America. This prompted the cemetery’s owner to consider building a museum and charging admission, until a grandson of Lucien Maxwell (Lucien and Pete Maxwell are buried in the cemetery) sued and won a permanent injunction that kept the cemetery free of charge. Also in 1938, the Works Progress Administration granted $8,657 to restore the old Lincoln County courthouse. The New Mexico legislature subsequently asked the federal government to designate the courthouse as a national monument. There were a few who viewed the creation of such a monument as immortalizing a cold-blooded killer, but their criticisms were ignored. Billy had become too much of a juggernaut. Although the courthouse failed to receive the federal designation, it was dedicated a state monument in a special ceremony featuring Governor John E. Miles on July 30, 1939. Also speaking that day were Billy’s old

friend George Coe and former territorial governor Miguel Antonio Otero. A crowd of approximately a thousand stood in the rain and watched the proceedings.

People like George and Frank Coe, Yginio Salazar, Jesus Silva, and Almer Blazer suddenly became minor celebrities, and tourists and newspaper reporters wanted to talk to them. George Coe was quick to catch on and published his own book,

Frontier Fighter,

in 1934. In addition to the people and places associated with the Kid, tourists and aficionados also wanted to see Billy artifacts, pieces of the True Cross, so to speak. The Kid had few personal possessions at the time of his death, yet certain individuals later claimed to have the Kid’s gun, spurs, knife, the broken shackles from his courthouse escape, even a wad of hair from one of Billy’s haircuts. Maybe some of these items were the Kid’s, maybe none of them. One artifact that could not be disputed, one that would command a high price on the open market, had hung behind the bar in Tom Powers’s Coney Island saloon since 1906. It was the gun that killed Billy the Kid.

Over the years, Powers had amassed an amazing collection of fire-arms that once belonged to famous westerners, including outlaw Sam Bass, Apache chief Victorio, El Paso marshal Dallas Stoudenmire, Texas gunfighter John Wesley Hardin, and Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa. In 1906, Powers had talked his friend Garrett into letting him display the Colt pistol used to kill Billy the Kid and also Garrett’s favorite Winchester rifle, both originally captured from Billy Wilson at Stinking Spring. Part of what made the saloon keeper’s collection so valuable was that he had written documentation for each weapon. Garrett gave Powers a signed affidavit giving the history of the weapons (along with their serial numbers).

“These guns are my prize souvenirs,” Garrett wrote, “because of their association with the Lincoln days and because I carried them through many trying times. During my life, I have owned many guns of all types and calabres [

sic

], but these two have been my favorites

and the ones that I relied upon to protect and defend the people whom I have served.”

According to the affidavit, Garrett gave Powers permission to display the weapons until he requested their return.

Polinaria Garrett with the gun that killed Billy the Kid.

Robert G. McCubbin Collection

In October 1930, Powers, who apparently suffered from depression, took a pistol, pointed it at his chest, and shot himself just above his heart; he died three months later. Polinaria Garrett sued the Powers estate for the return of her husband’s six-shooter, and the case received national publicity. The pistol that killed Billy the Kid was said to be worth more than $500. The Powers estate claimed that a financially desperate Garrett had finally sold the gun to Powers in 1907, and that

may very well have been true. Even if Garrett had not sold the gun to Powers, he certainly owed Powers money when he died. However, Polinaria testified that Pat had given her the weapon in 1904, and two years later he had asked her permission to let Powers display it in his saloon. Polinaria also claimed that Powers had promised that the gun would be returned to her after his death. Garrett’s widow was a small thing, but she could be just as feisty, if not more so, than her husband. The Garrett children loved to tell the story of how Pat once teased Polinaria about her English, and from that day forward, she never spoke to her husband in English again! She was not about to give up that pistol.

The El Paso County Court awarded the pistol to Polinaria, but the Powers estate appealed the decision to the Texas State Supreme Court. More than a year later, the appeals court affirmed the earlier ruling, that Pat Garrett had no right to sell the pistol without his wife’s consent. The pistol belonged to Polinaria. On October 7, 1934, as a newspaper photographer snapped pictures, Mrs. Pat Garrett stood on the front porch of her Las Cruces home and received the prized weapon from her attorney, a man with the intriguing name U. S. Goen. It was a rare triumph for the Garrett family, which had struggled mightily after Pat Garrett’s death. In early October 1936, Polinaria traveled to Roswell (the home of her daughter Elizabeth) where she was crowned Queen of the Old-Timers and rode in the annual Old-Timers parade. Two weeks later, she died from a heart attack. It seems strange that of all the surviving accounts and interviews from those who knew the Kid and Garrett, there is not one from Polinaria.

Fortunately, Polinaria was not around to see what film producer and director Howard Hughes did to her husband’s memory. In 1939, after success with such movies as

Hell’s Angels

and

Scarface,

Hughes chose Billy the Kid for his next big film. Hughes signed a contract with Garrett’s surviving children, Oscar, Jarvis, Pauline, and Elizabeth, presumably for the rights to their father’s story. Filming began

in Arizona late in 1940. The finished movie, titled

The Outlaw,

had a limited release in 1943 and then a wide re-release three years later. Panned by critics and condemned by religious groups,

The Outlaw

became a true blockbuster, primarily because of the film’s curvaceous new starlet, Jane Russell.

While most Americans were staring at Russell’s breasts, Pat Garrett’s children were looking at the disturbing portrayal of their father by character actor Thomas Mitchell. Mitchell’s Garrett was a dumpy, conniving, vengeful weasel of a man, and the Garretts were furious and humiliated. In March 1947, they sued the Hughes Tool Company of Houston, Texas, of which Howard Hughes was head, for $250,000 for breach of contract. The memory of their father, they claimed in the suit, was “cruelly and unjustifiably besmirched.” The result of their lawsuit is unknown. The family’s goal, a rather naive one, was to correct the false impression of their father created by the film. But truly, no one cared much about Pat Garrett anymore but them.

Just three years later, in 1950, the Garrett family was angered once again over a perceived threat to their father’s legacy. An old man living in the small town of Hico, Texas, was claiming to be Billy the Kid. A popular myth, one that existed even in Garrett’s time, was that Billy had not been shot down that summer night in Fort Sumner but had somehow survived. One version of the story had Garrett killing another man and claiming it was the Kid so he could get the reward. Another version had Garrett in cahoots with the Kid to fake the outlaw’s death. The myth played perfectly to the romantics, who hated the story about young, charismatic Billy, the Robin Hood of the Southwest, dying so tragically. But a living Billy meant that Garrett’s greatest claim to fame was all a lie. It was as if the Garrett family could not win. Their father was either the villain for killing Billy, or he was unworthy of his dedicated-lawman reputation because he had not really killed the Kid and perhaps committed fraud in the process.

The Texas man’s name was Ollie L. “Brushy Bill” Roberts, and

he had petitioned New Mexico’s governor Thomas J. Mabry for a pardon. Brushy, according to his El Paso lawyer, was old and tired of running, although exactly who or what he was running from at that late date is unclear. The governor agreed to meet with Brushy Bill in Santa Fe on November 30 to either verify Brushy’s claim or dismiss it. The meeting took place in the governor’s executive mansion in front of newspaper reporters, historians, Cliff McKinney (son of Garrett’s deputy, Kip), and Oscar and Jarvis Garrett.

When Oscar Garrett’s turn came to grill Brushy, he declined, saying he chose not to “dignify the occasion.” Turns out, Oscar did not have to. Brushy seemed confused and had trouble answering several pointed questions. He did not know who the Kid fought with in the Lincoln County War, he denied killing James Bell and Bob Olinger, and he had to be prompted before he could come up with Pat Garrett’s name. Perhaps Brushy was nervous in front of all those stern faces. The likely explanation is that Brushy Bill was a pathetic phony. The only thing he shared in common with Billy the Kid was a wild imagination. Mabry announced he would not consider a pardon, then or ever.