To Hell on a Fast Horse (27 page)

Read To Hell on a Fast Horse Online

Authors: Mark Lee Gardner

Brazel generally wore a black, broad-brimmed Stetson with a high crown that he pulled down close to his ears. His ruddy face was invariably clean shaven, and he kept his sandy hair cropped short. A scar ran down from the right corner of his mouth and over his chin. It came from either a knife cut, boyhood horseplay with his brother, or from being thrown by a bronc—take your pick. He got crossways with Pat Garrett after leasing the Bear Canyon ranch from Garrett’s twenty-five-year-old son, Poe, in March 1907. The Bear Canyon ranch was situated in the San Andres Mountains a few miles north of Garrett’s Black Mountain ranch, and although the lease agreement between Poe and Brazel clearly states that the ranch belonged to Poe, most contemporary accounts agree that it was Pat Garrett’s property, and Garrett certainly acted as if the ranch belonged to him. Garrett no longer had any stock to put on the place, and as he was intent on building his herds back up, he came up with a deal that said each year Brazel would give him ten heifer calves and one mare colt in exchange for the five-year lease. Garrett later claimed that Brazel said he was going to put three hundred to four hundred cattle on the place, but instead of cattle, Brazel moved in a herd of more than twelve hundred goats. Garrett was furious; five years with that many goats nibbling the sparse grass to bare nubs would spoil the place for all other livestock. Garrett was also upset to learn that his neighbor, Bill Cox, had fronted the money for the operation. Worse still, though—Print Rhode was Brazel’s partner in the goat herd.

Garrett tried to get the lease voided in court. He went to see the justice of the peace in Organ and swore out arrest warrants for both Brazel and Rhode based on an antiquated New Mexico statute that made it illegal to herd livestock closer than a mile and a half to a house

or settlement. The hearing took place in an Organ butcher shop in January 1908 and drew a large crowd; some of the onlookers, relatives and friends of the accused, were armed and tempers ran high. Rhode tried to pick a fight with Garrett, but as Print’s brother, Sterling, remembered, “Pat was too smart for it.” In a rather anticlimactic move, the justice dismissed the case—just one more thing that went wrong for Garrett. Soon there was talk that Garrett, Brazel, and Rhode were making threats against one another. Someone even overheard Garrett say that “they” would get him unless he got them first.

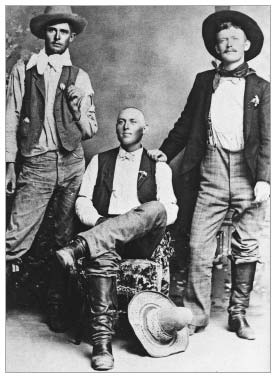

Wayne Brazel (seated) with Jim Lee and Will Cravens. Brazel had shaved his head as a joke.

University of Texas at El Paso Library, Special Collections Department

Garrett became more brutish and quarrelsome than ever. He got

into three or four fistfights in Las Cruces, and at fifty-seven years of age, the ex-sheriff came out of each one in worse shape than the one before. One day he wrote the governor in desperation: “Dear Curry: I am in a hell of a fix. I have been trying to sell my ranch, but no luck. For God’s sake, send me fifty dollars.”

But then something happened to offer the perfect solution to Garrett’s headache with the Bear Canyon outfit. Garrett was approached by James B. Miller in El Paso with an offer to buy the ranch. Miller told Garrett he had purchased a thousand head of Mexican cattle and they were to be delivered to El Paso on March 15. Although he had a ranch in Oklahoma, Miller preferred not to ship the cattle there until the fall and needed a place not far from El Paso to graze them. Garrett was not about to let this opportunity slip by because of a cussed herd of goats. He went to Brazel and talked the cowpoke into going to El Paso to see what might be worked out with Miller. After a short meeting, Brazel agreed to give up his lease as long as a buyer could be found for his goats. Miller found a buyer, his partner Carl Adamson, who also happened to be related to Miller by marriage. Adamson would take all twelve hundred goats at $3.50 apiece. Brazel returned to Bear Canyon and carefully counted his herd—instead of twelve hundred, he had eighteen hundred. Adamson was unwilling to buy that many, and Brazel was unwilling to give up the lease unless he did. Nevertheless, Adamson agreed to meet with Garrett and Brazel in Las Cruces to see if they could all come to some kind of agreement to save the deal.

Adamson traveled to Garrett’s ranch on February 28 and spent the night, and Garrett sent a note to Brazel that the meeting was still on for the next day. The next morning, a Saturday, Garrett got up early and took what was said to be “unusual care” dressing himself. At about 8:30

A.M

., Garrett said good-bye to Polinaria and the children and stepped into the two-horse top buggy with Adamson. He placed beside him a rather unusual folding shotgun manufactured by the

Burgess Gun Company of Buffalo, New York. Specifically designed for law officers, the 12 gauge, when folded, fit into a custom leather holster that allowed the wearer to quickly draw the gun and flip up its barrel into a locked position, ready to fire. This particular Burgess bore an inscription that identified the weapon as having belonged to Robert G. Ross of the El Paso Police Department. Ross had died of complications from appendicitis in 1899, and Garrett apparently bought the gun from the man’s widow.

Garrett grabbed the leather reins and slapped them against the rumps of the team, and they scooted off down the dirt track leading away from his ranch. At the Walter livery stable, about a half mile west of the Organ store and post office, Garrett drove the buggy right into the corral and up to the water trough so the horses could drink. The day had begun to warm up, but Garrett was still wearing his signature Prince Albert coat. Garrett spotted the fifteen-year-old Walter boy, Willis, hitching some horses to a box wagon and asked if the young man had seen Brazel. Willis pointed down the road at the wisp of dust still hanging in the air and said he had just left. Garrett waited for his horses to finish their drink and then backed the team up and started them down the road to Las Cruces. Willis watched them for a moment as they drove out of sight and then returned to hitching his horses.

About two hours later, Deputy Sheriff Felipe Lucero sat at his desk in Las Cruces thinking he needed to get some lunch. Suddenly, the office door burst open and in stepped a visibly distressed Wayne Brazel.

“Lock me up,” Brazel stammered. “I’ve just killed Pat Garrett!”

Deputy Lucero laughed at Brazel and accused him of pulling his leg. But Brazel insisted that he had shot Garrett, and Lucero, after pausing a moment to carefully study the man, decided he was serious. After locking Brazel in a cell, Lucero stepped outside to see Adamson, who was waiting in the buggy just as Brazel said he would be. Adamson confirmed Brazel’s story and Lucero retrieved the revolver that

Brazel had surrendered to Adamson. The sheriff then put Brazel’s horse in the stable and saddled up his own. Lucero had Adamson follow him in the buggy as he rounded up a coroner’s jury, which was not hard to do, as there were now several excited people out in the street dumbfounded at the news of Garrett’s death. Within a short time, Lucero led Adamson and the seven-man jury out of town, accompanied by Dr. William C. Field. The group rode in an easterly direction toward the storied Organ Mountains, their jagged, serrated peaks like one great claw reaching up to scratch the sky.

After traveling approximately five miles, they came upon Garrett’s body next to the road in the bottom of the wide Alameda Arroyo. Someone carefully removed the lap robe Adamson had used to partially cover the corpse. Garrett was lying on his back, his arms out-spread and one knee drawn up. About three feet from the body and parallel to it was Garrett’s Burgess shotgun, still folded and in its holster. Dr. Field noticed that there was no sand kicked up around the holstered gun, suggesting that it had been carefully placed there. Field and the jury also noted that Garrett’s trousers were unbuttoned, and although he wore a heavy driving glove on his right hand, his left hand was bare. Two bullet wounds were identified, one in the head and the other in the upper part of the stomach.

After Garrett’s body was taken to H. C. Strong’s undertaking parlors in Las Cruces, Field conducted a careful autopsy and found that the bullet to the head entered from behind—the doctor discovered several of Garrett’s hairs pushed into the entry wound. The bullet exited just over the right eye. Field also determined that the bullet in Garrett’s stomach ranged up through his body, suggesting that the bullet had been fired when Garrett was on the ground or falling down. Field found this bullet behind the shoulder and cut it out. One other item of interest was discovered, probably by undertaker Strong as he undressed the body: a check made out to Patrick F. Garrett in the amount of $50 and signed by Governor George Curry.

News of Garrett’s death flashed across the nation’s telegraph wires, with many newspapers running the story in their Sunday editions. These first published reports repeated what both Brazel and Adamson had told the deputy sheriff and the coroner’s jury: Brazel fired his pistol in self-defense when he saw Garrett go for his shotgun. First thing on Monday, Poe Garrett filed an affidavit against Brazel, charging him with the murder of his father. A preliminary hearing took place the next day, with the Territory’s attorney general, James M. Hervey, handling the questioning for the prosecution. There were high hopes that Carl Adamson’s testimony would provide some answers to exactly what had happened that day in the arroyo, but he was somewhat of a disappointment. Adamson testified that he and Garrett overtook Brazel about three-quarters of a mile from Organ. When they first spotted the cowboy, Brazel had been talking to someone in the road, but by the time they caught up to him, he was alone. The three continued on together, with Brazel sometimes riding alongside the buggy and at other times falling behind by a hundred yards or so. At a certain point, as Brazel was riding alongside, the conversation turned to the goats. The talk began calmly enough, Adamson recalled, but soon became heated as Garrett berated Brazel for somehow underestimating his herd by six hundred goats. Brazel tersely repeated his position that unless he could sell all of the goats, the deal was off.

Adamson, who claimed he was driving the buggy, said that Garrett and Brazel argued for about fifteen minutes as he guided the team along at a walk.

“Well, I don’t care whether you give up possession or not,” he remembered Garrett saying. “I can get you off there anyway.”

“I don’t know whether you can or not,” Brazel replied.

At this point, Adamson suddenly felt a need to urinate, so he pulled back on the reins and brought the team to a halt. After handing the reins to Garrett, he stepped out of the buggy on the right side, walked

near the front of the team, turned away from Brazel and Garrett, and unbuttoned his trousers. Brazel had stopped his horse a few feet forward of the buggy, reining his horse around a bit so that he was facing Garrett sideways, on the buggy’s left side.

Adamson next heard Garrett say in a high-pitched voice, “God damn you, I will put you off now!”

A second or two later, Adamson was startled by a “racket” followed by a gunshot. He spun around to see Garrett stagger and fall backward. He then saw Brazel, pistol in hand, fire a second shot. The second shot had come, Adamson said, just as quickly as a man can cock a pistol and shoot it.

The team jumped at the sound of the gunfire, but Adamson quickly grabbed the lines and wrapped them around the hub of one of the buggy wheels. Adamson then ran around the vehicle just in time to see Garrett stretch out his body and make a grunting noise. The famed lawman died without saying a word.

“This is hell,” Brazel said. “What must I do?”

Adamson told Brazel he better surrender to him. After covering Garrett’s body and tying Brazel’s horse to the back of the buggy, the two hurried to Las Cruces and the sheriff’s office. Adamson remembered that Brazel “seemed as cool as any man I ever saw as we drove into town.”

In the courtroom, Brazel appeared nervous and uncomfortable. His attorneys chose not to put him on the stand at the hearing, preferring to wait for the grand jury to take up the case. Bail was set at $10,000, which was promptly guaranteed by seven men, among them Bill Cox. Just one hour after the hearing, Brazel was walking the streets of Las Cruces.

Garrett’s body remained in state at Strong’s parlors for six days, where it was “viewed by thousands of people.” The funeral occurred on Thursday, March 6. It had been delayed for twenty-four hours to give two of Garrett’s brothers time to travel to Las Cruces from Loui

siana. Governor Curry and Tom Powers were among the six pallbearers. Powers, the El Paso friend Garrett stuck by at great cost to himself, also read the funeral sermon, which was a eulogy originally delivered by Robert J. Ingersoll, the famed orator and agnostic, over the grave of his brother. This choice for a tribute, as well as the speaker (Powers was also an agnostic), only seemed to confirm many people’s suspicion that Garrett was an atheist.

Nevertheless, few of Garrett’s friends and family would argue with the eulogy’s concluding sentence: “There was, there is, no gentler, stronger, manlier man.” Garrett’s body was interred at the Odd Fellows cemetery outside of Las Cruces.

Before and after the funeral, Garrett’s friends and family fumed about what they considered to be not only a murder, but a conspiracy. It was clear to them and others that Garrett’s death had not occurred the way Brazel and Adamson described it. For one thing, it was obvious that Garrett, too, had been urinating when he was killed—he had been found with his trousers unbuttoned and his glove off his left hand. And Garrett’s assassin, whether it was Brazel or someone else, had shot him from behind because the first bullet, they believed, had been to the back of Garrett’s head. They were also suspicious of the several men connected with the affair, and with good reason. James B. “Jim” Miller had an unsavory reputation as a killer—but not just any killer. Dr. J. J. Bush of El Paso, a friend of Garrett’s, wrote Governor Curry with a chilling assessment of Miller, whom he claimed to have known intimately for years.