To Hell on a Fast Horse (7 page)

Read To Hell on a Fast Horse Online

Authors: Mark Lee Gardner

On this particular August night, Windy and the Kid quickly got into it. One account states that Windy started razzing Henry about his new clothes and gun. Another claims that Windy refused to cough up the money the Kid won from him in a card game. Still another says that it all began as a friendly wrestling match. However it started, their words became heated, and Windy called Henry a pimp, and the Kid shouted back that the blacksmith was nothing but a son of a bitch. “[W]e then took hold of each other,” Cahill said. The blacksmith threw the Kid to the ground, pinning his arms with his knees and then slapping the Kid’s face.

“You are hurting me. Let me up!” the Kid demanded.

“I want to hurt you. That’s why I got you down,” Cahill said.

But Kid Antrim was, according to Pat Garrett, someone who “could not and would not stay whipped. When oversized and worsted in a fight, he sought such arms as he could buy, borrow, beg or steal.” Garrett may have been overstating the case, but not by much. Wiry

and fast, Henry began to work his free right hand around to his pistol. Windy saw what the Kid was trying to do and made a grab for the gun but failed. The Kid turned the pistol so its muzzle was pointing at Cahill and pushed it into the blacksmith’s belly. Cahill felt the sharp poke and straightened a little, anticipating the blast from the .45, which followed with a “deafening roar.” The initial stab of pain came not from the bullet but from the exploding black powder burning Cahill’s flesh around the entry wound, but this being a shot to the gut, the worst was yet to come. The Kid squirmed free as Windy slumped to the floor, smoke slowly rising from his clothing. Henry rushed out the door and jumped on a well-known racing pony named Cashaw, the property of gambler Joseph Murphey. No one tried to stop him.

Windy Cahill suffered through the night and into the next day. On his deathbed, he gave a deposition naming “Henry Antrim, otherwise known as Kid” as his killer. Gus Gildea remembered seeing Joseph Murphey on that Saturday, and Murphey was much more upset about losing his favorite horse than he was about the dying Cahill. Several days later, the gambler’s horse appeared courtesy of the Kid. It was also several days later that the newspapers reported that a coroner’s jury had found the Kid guilty of murdering Cahill. That settled it for Kid Antrim; he would not be returning to Arizona, nor would he be riding into his old home of Silver City—murder was a hanging offense.

There was one person the Kid desperately wanted to see, and although it would take him into an area where he would be easily recognized, the Kid decided to chance it. He located his brother on the Nicolai farm, situated on the Mimbres River near Georgetown (fourteen miles northeast of Silver City). Near the end of their emotional visit, the Kid speculated that he and Joseph would probably not see each other again. As the tears welled in both young men’s eyes, the Kid kissed his brother and said good-bye. Kid Antrim next visited his former teacher, Mrs. Mary Chase, now living in Georgetown. Re

membering that the teacher was a good judge of horseflesh, he showed off his handsome mount and related how he had shot and killed its former owner, an Apache Indian. The Kid liked to spin a good tale, however, and if this encounter with his teacher happened at all, it is more likely that he made up the story about killing the Apache rather than admitting he had stolen the horse from some cowboy. He then told Mrs. Chase he needed money.

“My mother gave him all the cash she had in the house, voluntarily,” the teacher’s daughter said years later, “and Billy stayed on the rest of the day, talking with mother and telling her about his experiences. Along toward evening, he took off.”

The Kid headed east across southern New Mexico, little knowing that he was riding to war.

War in Lincoln County

There was no law in those days. Public opinion and the six-shooter settled most all cases.

—

FRANK COE

K

ID ANTRIM DID NOT

ride across New Mexico Territory by himself. On October 2, 1877, he was spotted with a gang of rustlers on the old Butterfield Overland Mail route in southwestern New Mexico’s Cooke’s Canyon. Once again he had made a bad choice of associates—although as a fugitive himself, he had few options. The leader of the outlaw band, which liked to call itself “The Boys,” was Jesse Evans. Evans was approximately six years older than the Kid, and he stood five feet six inches tall, weighed around 140 pounds, and had gray eyes and light hair. Pat Garrett wrote that of the two, the Kid was slightly taller and a little heavier. Evans’s early history is as hard to pin down as Henry McCarty’s. At different times, he claimed both Missouri and Texas as his birthplace. He may have been the Jesse Evans who was arrested with his parents in Kansas in 1871, for passing counterfeit money. Tried before the U.S. District Court in Topeka, this Jesse was convicted and fined $500. Because he was so

young, he received no jail time and was “most kindly admonished by the court.”

Evans came to New Mexico Territory in 1872 and worked with cattle king John S. Chisum on the Pecos. That consisted primarily of stealing horses from the Mescalero Apaches and delivering them up to Chisum. It only got worse from there. By the time he and the Kid crossed paths, Evans had become one of the most hated desperadoes in southern New Mexico. Teaming up with the equally despised Mesilla Valley “rancher” John Kinney, he headed a gang of horse and cattle thieves numbering, at times, as many as thirty men. A cold-blooded killer and accomplished gunman, Evans was used to doing as he pleased with little fear of the law or anyone else. When his harshest critic,

Mesilla Valley Independent

editor Albert J. Fountain, urged the local citizenry to capture and lynch Evans and his gang, Evans threatened Fountain’s life (more than once), saying he would give the editor a “free pass to hell.” It was no idle threat.

The Boys, including the Kid, made their way across the

playas,

mountains, and deserts of southern New Mexico, freely taking the best delicacies, or what passed for delicacies, that each saloon or stopping place had to offer, ordering their nervous hosts to “chalk it up.” At Mesilla, Kid Antrim stole a splendid little racing mare that just happened to belong to the daughter of the county sheriff. The Boys continued eastward from the Mesilla Valley, traveling over San Augustin Pass, across the White Sands, and to the village of Tularosa, which they terrorized one evening with their carousing and the firing off of their ample supply of guns. The desperadoes next crossed the Sacramento Mountains and finally ended up at the Seven Rivers settlement in the Pecos Valley, approximately 250 miles from Mesilla. By this point, the Kid was no longer with them, having separated from the main party under Evans.

Hardly more than a spot on the road, Seven Rivers consisted of a single flat-roofed adobe of several rooms, one of which contained a well-

stocked store. Out back were several gravestones; close by, between low dirt banks, flowed the Pecos River. The “settlement” was actually a hodgepodge of scattered ranches and homesteads, surrounded by miles and miles of the finest grazing land in the Southwest, most notably the Chisum Range on the east side of the Pecos. Named for John S. Chisum, the range stretched from Seven Rivers north to the mouth of the Hondo, a distance of approximately sixty miles. Over the last few years, it had supported between twenty thousand and sixty thousand head of cattle, beef that went to fill government contracts at military posts and Indian reservations in New Mexico and Arizona. It had also supported some of Chisum’s Seven Rivers neighbors, who were not above helping themselves to his beeves, a situation that had erupted into the short-lived Pecos War earlier in the year.

The Seven Rivers store was owned by small-time rancher Heiskell Jones, and this is where the Kid turned up by mid-October 1877, possibly horseless after a run-in with Apache Indians in the Guadalupe Mountains—at least that is the story Antrim told. He was no longer Henry Antrim or even Kid Antrim. Now he was William H. Bonney. Some have speculated that he settled on Bonney because his father was not Michael McCarty at all, and his real father was a former husband or lover of his mother’s whose last name was Bonney. Regardless of what the Kid called himself, Heiskell’s wife, Barbara, took the gun-toting boy in. Known affectionately up and down the Pecos as “Ma’am Jones,” Barbara had a large family of her own to care for (between 1855 and 1878, she would have a total of nine boys and one daughter), yet she was famous for feeding, doctoring, and sheltering neighbors and strangers alike.

As related time and again by those who knew him, William H. Bonney had a charm or magnetism that was irresistible to the ladies; they wanted to mother him or take him for a roll in the hay. Ma’am wanted to mother him. “My mother loved him,” recalled Sam Jones. “He was always courteous and deferential to her. She said he had the

nicest manners of any young man in the country. She never could bear to hear anyone speak ill of him.” And both Sam and Frank Jones agreed that if “Billy had been a bad boy, Mother would not have wanted him around. And she was a pretty good judge of men.” Heiskell Jones freighted his own goods from Las Vegas to Seven Rivers, and the Kid went with Heiskell on one or more of these long trips. Billy also developed a close friendship with twenty-four-year-old John Jones, the eldest of the brothers. The Kid’s time at the Jones place may have lasted as few as three weeks or as long as three months. However long he stayed, it was plenty of time to make the Jones family loyal Billy the Kid supporters (and Pat Garrett haters) for the rest of their lives.

By this time, the Kid had become obsessed with guns and was impressive in his handling of them. Lily Casey, no fan of Billy’s, saw the Kid during this period and remembered that he “was active and graceful as a cat. At Seven Rivers he practiced continually with pistol or rifle, often riding at a run and dodging behind the side of his mount to fire, as the Apaches did. He was very proud of his ability to pick up a handkerchief or other objects from the ground while riding at a run.” Lily’s mother, the widow Ellen Casey, was bound for Texas with a herd of cattle and Billy hit her up for a job. But Mrs. Casey sensed, as her daughter later remarked, that Billy “was not addicted to regular work.” Lily and her brother, Robert, considered the Kid little more than a bum—he did not get the job.

Sometime that fall, Billy Bonney appeared at Frank Coe’s ranch on the upper Rio Ruidoso, looking for work. Coe was known to be both handy with a gun and quick to use one. But the Kid looked so young that Coe had a hard time taking him seriously. “I invited him to stop with us until he could find something to do,” Frank recalled. “There wasn’t much entertainment those days, except to hunt.” But there

was

entertainment in watching Billy play with his shootin’ irons: “He spent all his spare time cleaning his six-shooter and practicing shooting. He could take two six-shooters, loaded and cocked, one on each hand, his

fore-finger between the trigger and guard, and twirl one in one direction and the other in the other direction, at the same time.”

Billy soon found something to do. A short time earlier, on October 17, Jesse Evans and three of The Boys had been corralled by a posse under Lincoln County sheriff William Brady. Now they were being held in a miserable hole in the ground known as the Lincoln County jail. Completed that same month, the jail cells were in a dugout ten feet deep, its walls lined with square-hewn timber. The ceiling was made from logs chinked with mud and covered with dirt, and the only entrance was a single door. Prisoners were forced to climb down a ladder, which was then withdrawn and the door shut tight. Pat Garrett condemned the jail as “unfit for a dog-kennel.” Evans and the other prisoners whiled away the time playing cards and boasting that their friends would soon come to break them out. And sure enough, by mid-November, several of The Boys, among them Billy Bonney, had a plan to rescue their leader from the Lincoln hellhole.

IF ANY SINGLE CHUNK

of land embodied the American West, it was Lincoln County. The largest county in the United States at that time (nearly thirty thousand square miles), it spilled across the entire southeast section of New Mexico Territory. Stark plains rolled away to the horizon in its eastern half, bisected by slivers of water with evocative names like the Pecos and Rio Hondo. To the west, its rugged Sacramento, Capitan, and Guadalupe mountain ranges rose to nearly twelve thousand feet at their highest point. There were very few settlements, except for several ranching operations and the occasional Hispanic village or

placita

. The county’s human population numbered approximately two thousand; cattle numbered in the tens of thousands. A sole military post, Fort Stanton, was located just nine miles west of the county seat, also named Lincoln, and was there to keep watch over the still-wild Mescalero Apaches.

Nestled in the Rio Bonito Valley, the town of Lincoln was like other territorial settlements. Several adobe homes and stores, their thick mud-brick walls serving as a perfect insulation against the wearying heat of summer and the biting cold of winter, were scattered for a mile on both sides of a hard-packed dirt road. In the heart of the village, on the north side of this one and only street, stood the

torreón,

a three-story tower of rock and adobe constructed by residents years before as their main defense against plundering Indians. The town saw a fairly steady stream of settlers, who came to register land transactions or conduct business with the courts, at the same time purchasing supplies, picking up mail, and hearing the latest news.

The Hispanic citizens of Lincoln, who made up the majority of the town’s population, irrigated small fields on the Bonito, tended sheep flocks, and worked where they could as day laborers. Fort Stanton offered both civilian job opportunities and a market for livestock and produce. A few Lincoln families were involved in the overland freight

ing business; Hispanos were famed

arrieros

(muleteers) dating back to Spanish colonial times. To outsiders, this place was a world both exotic and backward.

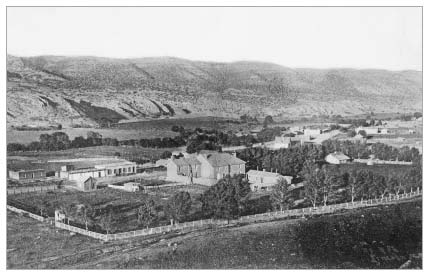

Lincoln, New Mexico Territory.

Center for Southwest Research, University of New Mexico

Most Anglos in the territory held strongly racist views toward Hispanos (and vice versa). Certainly, one could find affluent Hispanos in the territorial government and, more commonly, in county positions. But it was painfully clear to Hispanos what their place was expected to be. On October 10, 1875, Lincoln farmer Gregorio Balenzuela made the mistake of calling Alexander “Ham” Mills a gringo. Mills pulled out his gun and shot the man dead, after which Mills rode out of town unmolested. A year later, the New Mexico governor pardoned Mills for the murder. No wonder the Spanish-speaking Billy the Kid, who defied the gringo laws and humiliated the sheriffs and their posses, who rode like an Apache and kicked up his heels as gracefully as any vaquero, became, if not a favorite, certainly a sympathetic figure to native New Mexicans. To them, he was simply Billito or el Chivato.

IN THE EARLY-MORNING HOURS

of November 17, 1877, the dark figures of more than twenty horsemen passed quietly into Lincoln. It was The Boys, including Billy, and they rode straight to the county jail. At the jail, ten men dismounted and slipped through the main door, which was curiously unlocked. The jailer was asleep inside, but he soon awoke to a gun barrel pointed at his head. It was 3:00

A.M

., and the jailer watched as The Boys went to work on the trapdoor to the jail cells. The gunmen had brought heavy, rock-filled sacks, and they used these to bust through the wooden door to the dungeonlike cells below. Jesse Evans and the other gang members were waiting for them. A confederate had been able to get files and wood augurs to the prisoners, and Jesse and his pals had been busily working on their shackles in preparation for the breakout. Jesse and the others climbed up the ladder lowered to them, some with their leg braces still attached. It

was still dark and tranquil when the bunch rode out of town; most of Lincoln’s citizens did not get the news of the brazen escape until well after sunup.

For Evans and The Boys, it was now back to business as usual, stealing livestock and making death threats, with little to fear from the law. Not so for Billy—the law nabbed him a month later at Seven Rivers, where he was apprehended with a pair of horses that belonged to English rancher John Henry Tunstall. The Kid may have stolen the horses himself or traded with one of The Boys, but regardless, it was now his turn to spend some time in the subterranean Lincoln jail, and he did not like it one bit. He apparently requested a meeting with Tunstall, which must have gone well, because the Englishman had the Kid released and gave him a job on his Rio Feliz ranch.

Billy may have promised to testify against his friends in exchange for his freedom. The relationship between the Kid and Evans had been strained ever since Billy stole the little racing mare back in Mesilla. The mare had been Sheriff Mariano Barela’s daughter’s favorite, and the sheriff, Billy discovered a little too late, was a crony of Evans’s. Billy also may have been ticked off that none of The Boys came to his rescue in Lincoln like he had done for them. Whatever Billy’s reasons, by joining Tunstall he had officially taken sides in one of the most famous and bitter feuds in the American West, an ugly struggle for profits and economic dominance that became known as the Lincoln County War.