To Hell on a Fast Horse (10 page)

Read To Hell on a Fast Horse Online

Authors: Mark Lee Gardner

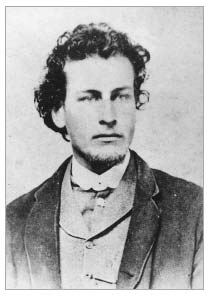

Keeping out of Roberts’s sight, Dick Brewer and one of his men

made their way from the big house to the sawmill. Brewer crawled out into the mill’s log yard, from where he had a clear view of the office door from 125 yards away. When Brewer thought he saw some movement in the doorway, he took a shot. The bullet hit the office’s back wall with a thud, and that immediately got Roberts’s attention. Roberts looked out toward the log yard, but he patiently held his fire. After a short, tense few moments, he saw a hat slowly rising above one of the logs. When he guessed there was enough hat above the log, he squeezed the Springfield’s trigger. A loud crack and an explosion of white smoke came from the office door. In the log yard, Dick Brewer tumbled backward. He was dead.

Richard “Dick” Brewer, leader of the Regulators.

Robert G. McCubbin Collection

When Billy got word that Brewer had been killed, he exploded with anger, yelling at Dr. Blazer to put Roberts out of the house. Blazer refused. The Kid then told the old man he would kill him if he did not do what he was told, but Blazer said Roberts would do the same thing if he attempted to force him out of the office. Billy called Blazer a damned old fool and threatened to burn his house down, but Blazer, unshakable as ever, responded that there was nothing he could do to stop that.

Demoralized, disgusted, and shot all to hell, the Regulators stormed off to the corral, got on their horses, and rode away, leaving the Blazers to deal with Brewer’s body and the wounded Roberts. Roberts died the next day, and he and Brewer were buried side by side on a hill overlooking the settlement. Frank Coe later said that Andrew Roberts was probably the bravest man he ever met.

FOR THE REGULATORS, THE

next ninety days were a blur of shooting scrapes, bailes, and hard riding. On April 18, a grand jury indicted Billy and three of his fellow Regulators for the murder of Sheriff Brady, and Billy was again named, along with five other Regulators, for the killing of Roberts. The House forces received their fair share of attention from the grand jury as well. Jesse Evans and, as accessories, Jimmy Dolan and Billy Mathews were among those indicted for the murder of John Henry Tunstall. Alexander McSween, on the other hand, achieved a minor victory when the grand jury exonerated him of the criminal charge of embezzlement, at the same time commenting that it regretted “that a spirit of persecution has been shown in this matter.”

Despite the indictments, the Regulators remained just as determined to hunt down Tunstall’s killers. McSween, acting upon the authority of Tunstall’s father in England, posted a $5,000 reward for the apprehension and conviction of the culprits. The Scotsman sounded

a lot like Billy when he wrote Tunstall’s sister that “There will be no peace here until his murderers have paid the debt.”

No peace was right. Gun battles between the two factions broke out wherever they met (or, rather, caught up to each other)—in the streets of Lincoln, at San Patricio in the Ruidoso Valley, and even at Chisum’s South Spring ranch on the Pecos. Frank MacNab, who had replaced Dick Brewer as the Regulators’ captain, was killed in an ambush on April 29. Two weeks later, the Regulators shot and killed Manuel Segovia, known as “the Indian,” in a raid on a Dolan cow camp (Segovia had been a member of the posse that murdered Tunstall). The feud consumed everyone and everything in the region, and it was virtually impossible for anyone to remain neutral. The Dolan men forced settlers to feed and shelter them, or worse—to join their posses—and the Regulators did the same. Jimmy Dolan brought in even more gunmen from the Seven Rivers country and the Mesilla Valley.

The final showdown came in mid-July in the county seat, in what would be called the “Big Killing.” McSween had been dodging the Dolan crowd for weeks when he received news that appeared to be a dramatic turn for the better: William Rynerson, the district attorney and a fierce Dolan supporter, and Governor Axtell were to be removed from office. Weary of roughing it, McSween was determined to return to Lincoln with a strong show of force, nearly sixty men in all. Riding with him, of course, was eighteen-year-old Billy Bonney, who had demonstrated that not only could he handle a gun and ride as well as any man in Lincoln County, but he also had grit—and, even better, he shot to kill. The plan was that McSween would go to his home, the Regulators would secure key buildings in town, and they would wait. Whatever happened, McSween decided, nothing could make him leave his home again—not alive, that is.

Just after dark on July 14, a Sunday, McSween and his followers rode into Lincoln. The night’s full moon had not yet spilled its light

into the canyon, which meant the riders could take up their positions without being detected. The structures being secured were the Ike Ellis store and dwelling, the José Montaño store, and the McSween house, all thick adobe buildings. Sheriff George W. Peppin, Lincoln County’s most recent sheriff and, naturally, a Dolan man, was staying at Wortley’s Hotel, as was Jimmy Dolan. Most of the sheriff’s men were out hunting the Regulators; the dozen or so he had in town were divided between Wortley’s and the old

torreón.

News of McSween’s arrival with his large force came soon after dawn. One of Reverend Taylor Ealy’s pupils burst into the Ealy residence in the old Tunstall store: “There will be no school today,” the boy said excitedly, “as both parties are in town.” Sheriff Peppin sent a rider to find the rest of his posse and tell them to hurry back to Lincoln.

Billy was in the McSween house along with fourteen other gunmen, as well as McSween and his wife, Susan; Susan’s sister Elizabeth Shield and her five children; and, ironically enough, a health seeker by the name of Harvey Morris. The flat-roofed adobe house was built in the shape of a “U” and contained as many as nine rooms; the opening of the U faced the Bonito River. Billy and the other combatants began to prepare for a long siege, placing heavy adobe bricks in the windows and carving gun ports in the walls. Later that day, a loudmouthed deputy named Jack Long was sent to serve warrants on the Kid and others at the McSween place. Four months earlier, an inebriated Long had told the Reverend Ealy that he wished a whore had come to Lincoln instead of the minister and that he had once helped hang a preacher in Arizona. Long’s typical bluster did not go far with the boys at McSween’s, though. A volley of gunfire sent him heading backward.

By that evening, the rest of the Dolan faction was back in town, approximately forty men in all, including Jesse Evans—free on bail from the Tunstall murder charge—and Mesilla Valley hoodlum John

Kinney. The two sides began shooting and yelling, and this continued sporadically into the next day and night. Fresh water was a problem for the defenders in both the McSween house and the Montaño store, and communication was nearly impossible between the three groups of McSween fighters. But at the same time, Sheriff Peppin was unable to get any real advantage. Nothing other than a cannonball was going to penetrate those solid adobe walls—and that is exactly what the sheriff had in mind. In a note to Fort Stanton’s post commander, Lieutenant Colonel Nathan A. M. Dudley, Peppin requested the “loan” of a mountain howitzer to aid him in persuading the McSween men to surrender. Peppin, who held a commission as a deputy U.S. marshal, asked Dudley to do this “in favor of the law.” The law, however, was the new Posse Comitatus Act, passed on June 16, 1878, and it specifically prevented the use of U.S. soldiers as law enforcement.

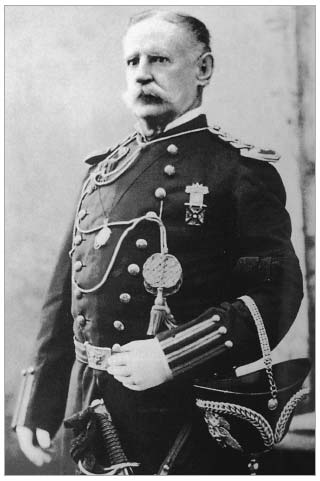

Dudley sent his regrets to the sheriff via a courier, and that should have ended the matter. But as the courier was riding into Lincoln, he was fired upon, allegedly by men in the McSween home. Dudley ordered an investigation, which again resulted in some of his men coming under fire. Then, on the evening of July 18, Jimmy Dolan made a trip to the fort to see Dudley. The fifty-two-year-old lieutenant colonel, known as “Gold Lace Dudley” because of his penchant for accessorizing his uniforms, was a career army man with not much of a career. He was arrogant, noisy, vindictive, a heavy drinker, and, not surprisingly, generally unpopular with his fellow officers. And he clearly favored one side over the other in the Lincoln County War. Earlier in the year, he had been defended in a court martial by Thomas Benton Catron, the U.S. attorney for New Mexico, who also happened to be one of the wealthiest men in the Territory and a central figure in the Santa Fe Ring. A longtime Murphy-Dolan backer, Catron now controlled The House’s assets, having foreclosed on J. J. Dolan & Co. back in April.

According to a witness who claimed to have overheard the conver

sation between Dudley and Dolan, the post commander told Dolan to go back to Lincoln and keep the McSween party at bay and he would be there by noon the next day. Later that same evening, Dudley consulted with his officers about sending troops into town. Their sole purpose, he said, would be to protect the women and children and any noncombatants caught in the cross fire. The officers knew better than to disagree with their commanding officer, and they unanimously concurred with his plan.

Lieutenant Colonel Nathan A. M. Dudley.

Collection of the Massachusetts Commandery, Military Order of the Loyal Legion, U.S. Army Military History Institute

The next day, at approximately 11:00

A.M

., the sound of drums was heard to the west of Lincoln, the

rat-a-tat-tat

growing louder as a military column came into sight. Dudley rode in the lead, followed by four officers, eleven buffalo soldiers (black cavalrymen), and twenty-four white infantrymen. The soldiers wore their full-dress uniforms—nothing less would do for Gold Lace Dudley. Far overshadowing the spiffy appearance of Dudley’s command, however, were the twelve-pound mountain howitzer and Gatling gun they had with them. The McSween forces dared not fire on the soldiers, and as the column moved past the McSween home, Dolan’s gunmen followed along, taking up better positions around the Scotsman’s house.

McSween and his men had definitely not prepared for troopers with artillery. Dudley established his camp across from the Montaño store and ordered his howitzer aimed at the building’s front door. This was too much for the defenders inside, and they prepared themselves to flee the building. They covered their heads with blankets to hide their identities and burst out of the store, running east down the street to join their compadres in the Ellis store. When the artillery was faced in that direction, a similar scene ensued, the escaping Regulators firing parting shots at Sheriff Peppin’s men who were pursuing them. Within a matter of minutes, McSween lost two-thirds of his fighters.

McSween wrote a hasty note to Dudley, which was carried out of the house by his ten-year-old niece: “Would you have the kindness to let me know why soldiers surround my house? Before blowing up my

property I would like to know the reason.” Dudley responded flippantly through his adjutant: “I am directed by the commanding officer to inform you that no soldiers have surrounded your house, and that he desires to hold no correspondence with you; if you desire to blow up your house, the commanding officer does not object providing it does not injure any U.S. soldiers.” Susan McSween left the house next and pleaded separately with Sheriff Peppin and Dudley. Both men were hostile to her, especially Dudley. Susan returned to her husband’s side. If there was ever any doubt as to whose side Dudley was on, there was none now.

Sheriff Peppin now turned his full attention on the Scotsman’s home. If McSween and his remaining men would not surrender, then he would burn them out. At about 2:00

P.M

., one of Peppin’s men started a fire at the summer kitchen that was situated in the house’s northwest corner. Heavy gunfire prevented the Regulators from extinguishing the flames, but because the house was adobe, the fire burned very slowly, room by room. Coughing and gasping from the smoke, their eyes stinging, the men did what they could to fight the blaze from the inside. There was no water, of course, but by pulling up floorboards and moving furniture, they robbed the flames of fuel. The ceiling, with its wooden

vigas

and

latias,

was where the fire had taken hold, however, and there was little that could be done there. But if they could slow the fire enough, it would be dusk before the defenders would be forced to evacuate the home; some of them might get away. Peppin’s men would be anxiously waiting for that moment as well, but it was far better to sell one’s soul with guns ablazin’ than to be consumed alive by the flames.