Tom Brokaw (12 page)

CHARLES BRISCOE

“If you've got a job, there's a way to do it. As a farm kid I

didn't have anyone to ask; I just had to figure it out. So when

I went to Boeing, that's just what I did.”

A

MERICA WAS

a modern industrial power when it entered the war, and so the machinery was already in place for converting production from domestic needs to the tools of warâtanks, jeeps, ships large and small, submarines, small-bore rifles, and artillery pieces large enough to launch a shell the size of a full-grown hog. No industry was as busy or as inventive as the airplane business. Aircraft designers were drafting new fighter planes and long-range bombers almost daily.

All this production required another kind of armyâone of workers. There was no shortage of men and women ready to earn a steady wage after the long, lean years of the Great Depression. Moreover, most of them were used to hard work and long hours. Many had grown up on farms where the days ran from daybreak to past sundown, where work meant just thatâworkâthe back-breaking, callus-making kind of work in hayfields and cattle barns, in primitive kitchens and rudimentary laundry rooms.

Charles Briscoe grew up as the son of an itinerant farmer who moved restlessly across the Great Plains, looking for work. Briscoe came of age in the Dust Bowl. “On the fourth of March, 1935,” he says, “I was in a car being pulled by my uncle's car. It was a beautiful day. The sun was shining. Then it turned dark as quickly as you can clap your hands. I could see nothing. I got out of the car and felt my way to his car. My mother lit a coal-oil lamp and held it in the window of the house and we drove toward that.”

He tells another story about all that dust in those days. “My mother would hang wet sheets over a frame on our bed to keep the dust out of our lungs when we went to bed. The neighbors all around us lost children because they didn't take the precautions my mother did.”

And two more stories of those days of poverty:

“One of the happiest days of my lifeâI was about in the seventh gradeâwe were farming in Kansas and I was trying to plow with a team of horses, walking behind, trying to keep the plow straight. My dad came home with wheels and a seat for the plow. I'll never forget it.

“When my mother had to have work done on her teeth we had no money, so I went to the dentist and offered to work for him in exchange for the work she needed. I washed his car and I did such a good job he hired me to work around the office. I washed the floors and the windows, cleaned the bathroomâanything he wanted. He said I was the best help he'd ever had, and he gave me the keys to the office so I could come and go when I wanted. I told him my mother taught me to clean house.”

A neighbor had a John Deere tractor in need of an overhaul. He asked Charles whether he could handle the job. In fact, Charles had never worked on a John Deere, but that didn't discourage him. The neighbor's wife drove him to town to buy the parts. He took the tractor apart, installed the new parts, and put it back together again.

“I had a wonderful dad, but after any of us children got to a certain age we started working and never kept a paycheck. It all went into the family kitty. I could find a job at age fifteen when my father couldn't. I just had natural skills. I got a job cutting broom-corn by hand. The rows were a mile long. The boss told the other men that if they couldn't keep up with me, they could leave. My dad couldn't keep up, so I'd cut his row, too.”

His father was having a more difficult time on his own farm, according to Briscoe. “We planted wheat five years straight and only one year the crop came in. We got twenty-five bushels an acre and sold them for twenty-five cents a bushel.”

By the time Briscoe was high school age, the family was living on a farm thirty-five miles from Arkansas City, Kansas, where his sister was teaching school. He wanted to complete his studies, so he hitchhiked to town to attend the high school. “I studied in the city library until they closed it,” he said, “and then I would pick up an abandoned newspaper and go to an abandoned house. I'd sleep on the newspapers. My main meal was salted peanuts because you could get them for a nickel. That went on for three weeks until we sold a pig. Then I could rent a room for a dollar and a half a week.”

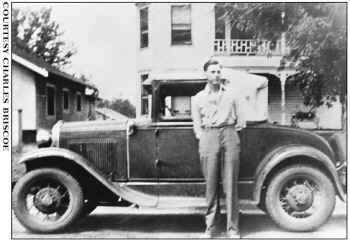

Charles Briscoe, junior college, 1938

After graduation Briscoe left for California, where he enrolled in a sheet metal school, learning the ways of this new trade that blended perfectly with his eye for design and his instinct for a job well done. He returned to Wichita, Kansas, in 1940 with his new craft, for a job at the Stearman Aircraft Division, a branch of Boeing. The plant was already gearing up for the possibility of war, turning out light training planes and working on a supersecret project: the development of the B-29, the Superfortress, the long-range bomber the Army Air Corps desperately needed.

Briscoe knew the mission was urgent. “We knew the B-17s and B-24s didn't have the range to get to Japan. We had to have the B-29 to win the war and get the men home from over there. We worked seven days a week, often twelve to fourteen hours a day.” He says Boeing tried to find farm boys for their workforce “because we were used to long hours. Out on the farm we got up at four

A

.

M

. to milk the cows and then milked them again at eight-thirty that night. So hard work wasn't anything.” There was another dividend for Boeing in hiring farm boys at a time when the aircraft industry was in a do-or-die creative phase. Farm boys were inventive and good with their hands. They were accustomed to finding solutions to mechanical and design problems on their own. There was no one else to ask when the tractor broke down or the threshing machine fouled, no 1-800-CALL HELP operators standing by in those days.

My father, Red Brokaw, was a blue-ribbon member of that fix-it generation. My mother learned not to say aloud that she needed, say, a new ironing board, because my father would immediately build her one. She liked to buy something from the store occasionally. When I was a young man in need of spending money I mentioned that I could mow many more lawns if I had a power mower. I had a snazzy new model from Sears Roebuck in mind. My father went to his workshop and built a mower using an old washing machine motor, welded pipes for handles, a hand-tooled blade, and discarded toy wagon wheels mounted on a plywood platform. He painted it all black and it was a formidable machine. At first I was embarrassed, but then as it drew admirers I was proud of its homespun place in a store-bought world.

During the war, Red and his pals made all of our Christmas toys. Later in life, when I took our daughters home for a Christmas visit, it snowed hard and we were determined to go sledding. By then my parents had gotten rid of all of our childhood sleds, so Grandpa Red took my daughters down to his workshop and turned out a wooden sled in less than an hour. It went down the hill as swiftly as any Wal-Mart model. My daughters, grown now, treasure the memory.

My father and his friends were like Charles Briscoe. They loved to make things work, and although they were not formally trained they had an instinct for design. Briscoe worked in tool design at Boeing. “I had to learn it all on the job because I had no experience like that whatsoever,” he says. “We couldn't always get the materials we needed, so we'd make some tools out of Masonite or maple wood. They didn't last long, but then we'd make another one using just a band saw.”

Briscoe's parents were also used to hard work, so he got them jobs at the Boeing plant. His father was sixty-five at the time and his mother was in her late fifties.

They were all part of a team effort to build the new, long-range airplane. Nothing like it in aviation had ever been undertaken before. Just four years earlier, Boeing had produced a total of one hundred airplanes from its Seattle and Wichita plants. Now the military wanted more than five thousand a year, including this new, long-range bomberâthe first mass-produced, pressurized heavy bomber. It had a wingspan almost fifty feet longer than a modern 737. It would be the single greatest airplane program during World War II.

It was America at its inventive best. “Today you have to have FAA approval,” Briscoe says, “but on the B-29 the engineers were drawing plans and we were making parts before it was approved by anyone. Some of what the engineers gave us were just pencil sketchesânot even blueprints.

“We started putting beds in the B-29 because we figured the pilots would be in there a long timeâbut then we decided there wasn't enough room, so we had to redesign and take the beds out.”

In February 1943, a prototype B-29 was tested near Seattle with tragic results. It caught fire and crashed, plowing into a building near Boeing Field. All twelve crew members and nineteen people on the ground were killed.

In June 1943 the first production B-29 rolled off the Wichita assembly line. Briscoe will never forget the moment. “All of us went out to the front of the hangar to watch the new B-29 take off, and as it took off, smoke started coming out! We thought we'd lost everything. But it turns out they'd left an O-ring off one of the oil lines.

“The next day it took off and it was beautiful. We knew we had a successful airplane. It looked as big as an apartment houseâand I had built it.”

What he did not know at that moment was that the B-29 Superfortress would be the means of delivering the bomb that would bring Japan finally to its knees. It was a B-29 called the

Enola Gay,

named after the mother of the pilot, Colonel Paul Tibbets, who dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshimaâthe beginning of the end for imperialist Japan.

Charles Briscoe was not on the job the day the news came of the bombing of Hiroshima. He was in the Navy. “I was twenty-nine years old and I had two sons and I wanted the world to be safe for them, so I volunteered for the Navy in 1945. I was in for just nine months before the war was over. I definitely knew it had to be a B-29 carrying the bomb, because that was the only airplane we had that could make it that far. I was thrilled. I realized it was sad that all those Japanese died, but how many Americans would have been killed without the atomic bomb?”

After the war and his short-lived Navy career Briscoe returned to Boeing and spent the rest of his working life there, helping develop parts for the new airliners that were rapidly filling the skies around the world. Briscoe was an invaluable troubleshooter for Boeing. Going back to the time when they were inventing the B-29 day by day, he had developed a knack for designing and producing airplane parts. After he retired at sixty-seven, Boeing brought him back at the age of seventy to work on special projects. The company tried to bring him back after his eightieth birthday as well, but there he drew the line.

He's proud of the work he did on the Boeing 737, the world's most popular airliner. The skin of the 737 was first formed by two sheets of metal that met the thickness specifications but exceeded the weight restrictions. So Briscoe and the Boeing experts designed a series of waffle-shaped cutouts on the inside to reduce the weight. It was one of many challenges the former farm boy relished during his long career at Boeing.

It's been a much better life for Charles Briscoe than he expected when he was moving around the Dust Bowl with his parents as a teenager. What he learned then, however, served him well. He learned to work. As he says, “If you've got a job, there's a way to do it. As a farm kid I didn't have anyone to ask; I just had to figure it out. So when I went to Boeing, that's just what I did.”

It's a way of life for him. Now in his eighties, Briscoe is still fixing what's broken. “I buy run-down houses and remodel them and rent them. Anything that needs to be done, I do itâthe plumbing, the electrical. I roof 'em, I do the Sheetrock, patch the holes, all of that.”

Briscoe teaches his children and grandchildren by example. “The kids nowadays,” he says, “their parents buy them fancy cars and depend on someone else to keep them running. When all my grandchildren wanted cars I bought five hail-damaged carsâwe get a lot of hail in Kansas. I got them for about three thousand dollars each instead of ten thousand or fifteen thousand dollars. I welded a finishing nail in each of the dents, bent it over, ground it smooth, and filled it in with body putty. By the time we finished, the cars looked brand-new. I had my grandchildren help me so they'd learn that if you want something badly there's a way to get it.”

DOROTHY HAENER

“A number of my men friends said it wasn't a place for

women. They said I'd be too nice. I had to fight them.”

I

N OTHER FACTORIES

converted to wartime production, other children of hard times were finally making a good wage. Many of them were women, able to take their place on the factory floor only because the men were needed in uniform. One of them was Dorothy Haener, a strong-willed young woman from a hardscrabble Michigan farm run by her single mother. Dorothy says she developed a sensitivity at an early age to how women were treated in the workplace. Recently she told a niece “how disturbed I was when my eighth-grade teacher was fired because she had been married the year before.” That was not an uncommon practice in small-town America and in the rural areas. Teaching jobs were reserved for single women and men who were “heads of household.” In the reasoning of the time, a married woman would not qualify as a head of household.

Once Haener graduated from high school, she went to work at a Ford Motor Company plant in Willow Run, Michigan, where production was already underway on the B-24 bombers that would be so critical in the war in Europe. Haener makes it clear she was not motivated by patriotism alone. “What people forget now is that people went to work because they wanted to live. Years later, when the women's movement came along, I heard people talking about work that was âmeaningful' to them. I consider myself lucky that eventually I found work that was meaningful, but I was always willing to work for just wages.”

It was while working as a B-24 parts inspector at Willow Run that Haener began to reevaluate her life. Until then, she says, “I had always expected to get married and raise a family, something modern women's organizations don't like to hear me say, but that's the way I was raised.” Working nine-hour days, six days a week alongside men in the plant, however, made Haener realize she could have an independent life. She was proud of her work and happy with the money she was earning.

In the summer of 1944 that life ended for Dorothy Haener. She was laid off when KaiserâFrazier Industries took over the plant to prepare for the postwar years. It had no room for women. Kaiser declared it would hire the best of the returning servicemenâand who was going to argue with that? Haener thought there was room in the plant for men

and

women. After all, she'd done her job well. Why should she be penalized?

Her efforts at getting hired back at her old wage were unsuccessful. She went to work in a toy factory for much lower pay. She assembled cheap toy guns and plotted to return to the Willow Run plant and her old salary.

In the fall of 1946 she was hired back at KaiserâFrazier but in a clerical position at a lower wage than what she had earned during the war. She quickly found a new calling: union activist. It was the beginning of the glory days of the United Automobile Workers union under the enlightened leadership of Walter Reuther, and Dorothy Haener became an eager acolyte.

She began by organizing the office workers and engineers, motivated by her anger at having been demoted summarily from parts inspector to secretary and by the wage gap between those on the production line and those working in the offices. “I can't speak for why the engineers organized,” she says, “but for the women it was simply a matter of money.”

Haener's success as an organizer of her colleagues and her passion for fairness won her a following within the ranks, and soon she was elected a trustee of her UAW local. She'd also gotten to know Walter Reuther, who admired her skills so much that he brought her into the national headquarters as an organizer of engineering and office staffs around the country.

Although Reuther was an articulate and committed champion of equality across all linesârace and genderânot everyone in the labor movement shared his philosophy. Haener learned that she was most successful when she didn't single out women as an issue. She says women had to be smarter and better dressed to hold their jobs, but “if you played the equality thing too much,” she says, “you turned off men. The message played best when I focused on better pay and control of the workplace.”

At headquarters she was also an important force in raising the place of women within the UAW at every level, including the establishment of a separate women's department for the union. Irving Bluestone, then an administrative assistant to Reuther, is now a professor of labor studies at Wayne State University and he remembers, “Dorothy was actively outspoken and put pressure where pressure needed to be placed.”

Sometimes she did that by personal example, often meeting resistance from her male colleagues in the labor rank and file. She decided to run for the powerful bargaining committee within the UAW, the elite group that goes head-to-head with management in hammering out the terms of a new contract. Many of her male colleagues opposed the idea of a woman on that critical committee. It was the labor movement equivalent of a woman in the cockpit of a fighter jet.

“A number of my men friends said it wasn't a place for women. They said I'd be too nice. I had to fight them. Finally I won in an open-caucus vote and I lost some male friends over that. They wanted women around but they didn't want them to have any responsibility.” It still hurts Haener to discuss personal attacks leveled against her by her male colleagues. They raised questions about her morality and whispered slanderous rumors about her personal life. When she asked a union lawyer for advice, he told her to ignore them and devote all of her energies to her union commitments.

Later, one of the men in the anti-Haener movement came to her and apologized for his role. That eased the pain some, but the larger lesson for Dorothy was that women would have to go through those kinds of experiences if they wanted an active role in the union movement. That's what she wanted, and she was devoting her life to it.

Haener never married for largely that reason. “By the time the war ended,” she says, “I was too independent to get married.”

Haener met Betty Friedan, the author of

The Feminine Mystique,

when Friedan was touring the country for President Kennedy, assessing the issues of women and equality. As a result of those early meetings Haener became a founding member of the National Organization for Women, NOW. She's no longer on the board, and while she does feel that NOW has filled a need in promoting equality for women, she believes that it and other women's organizations have come up short in pushing hard for equal pay.

“We've made some improvements,” she says, “but we still have a long way to go. So many of the younger generation don't know how far we've come. . . . They don't realize that what's given to them in the law can be taken away when the law isn't enforced.”

Dorothy Haener got into the labor movement because she felt cheated on the job and in her paycheck when the war came to an end. It's what keeps her going now. “Wages affect women more than anything else,” she says. “Take child care. We pay women who take care of children less than we pay people who take care of animals.”

The war years gave Dorothy Haener a chance to earn a good wage, to contribute something to her country, and to learn a good deal about herself. She not only became a seminal figure in the postwar women's movement, she also chaired the Michigan Civil Rights Commission in the eighties and testified several times before Congress on the issue of equal pay for equal work.

She's now retired but she hasn't given up her long fight; she volunteers to walk picket lines in the Detroit area when needed and discusses with her nieces the continuing need to make sure women are treated fairly on payday. She's confident they understand. After all, one of them is now an engineer at General Motors and a mother. Dorothy's niece has maternity leave and child-care benefits. The bitter experience of her aunt Dorothy more than fifty years ago and how it changed her life paid off for Dorothy's niece, and for thousands of other women who are just now beginning to take their place alongside men in the workplace and at the pay window.