Tom Brokaw (13 page)

HEROES

“Hero” is a description tossed around lightly these daysâlike “star” or “celebrity”âanother significant difference between the closing days of the twentieth century and the century's middle years, World War II. During the war the use of the phrase “You're a hero” was likely to bring on the quick rejoinder, “No, I'm not; I'm just doing my job hereâlike everyone else.” The fighting men and women were so dependent on each other and shared so many common experiences they were embarrassed to be singled out.

Some acts of heroism, however, were so breathtakingly conspicuous, so daring and vital to the military mission, they could not be overlooked or turned aside. In many instances they changed forever the lives of those who were decorated. Others who were decorated returned to the lives they would have had without the medals and the attention.

If there is a common thread among the major medal winners, it is the same modesty expressed by Army nurse Mary Louise Roberts Wilson when she received the Silver Star. Almost to a person they have said to me, “I didn't

win

this medal. I merely accepted it for all the people who were with me.” Nonetheless, they

did

win it, and the very qualities that led them to take great risks to save others served them well once they returned home.

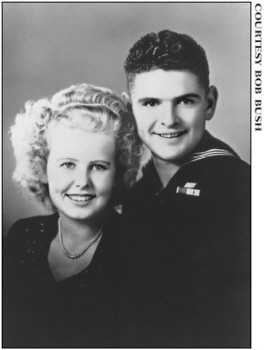

Bob and Wanda Bush, wartime portrait

BOB BUSH

“Everyone should learn the meaning of that famous little

four-letter wordâ

work

.

”

B

OB BUSH

has been married to his high school sweetheart, Wanda, since 1945, when they were both eighteen. They have three grown children and the comfortable lifestyle that goes with Bob's great success in the lumber and building supply business in the state of Washington. He has one blind eye to remind him of that day on a ridge on Okinawa. He went to the aid of a gravely wounded Marine officer that day, one of the deadliest days in the fight for control of the Pacific, for the planned invasion of Japan.

He has something else to remind him of that day: the Congressional Medal of Honor, the nation's highest commendation for battlefield valor “beyond the call of duty.” There were 440 Medals of Honor awarded during World War II, 250 of them posthumously.

When Bob Bush earned his medal he was fulfilling a promise to his mother. As he left for basic training as a Navy medic the year before, when he was seventeen, he told her, “Mom, I'm going into the service to help people, not to kill them.” Bob knew that was important to his mother, a single woman who worked as a nurse in an Oregon hospital. They had already been through so much together, mother and son.

They lived in the basement of the hospital in which Bob's mother worked and money was very scarce. But at an early age Bob had a flair for commerce. As a teenager, when he saw how hot and sweaty it was for the men working in the holds of the ships in the harbor at Raymond, Washington, his hometown, he brokered a deal with a local grocer to supply the workers with cold soft drinks. It was a profitable enterprise and Bob learned lessons early in how to fill a need, arrange credit, and most of all, provide good service.

By 1943, however, when he was in high school, the war was raging and he wanted to be a part of it. So he dropped out of school to join the Navy medical corps. He reported for basic training in Idaho, and less than a year later he was on an amphibious assault vehicle loaded with Marines, going ashore at Okinawa for what everyone knew would be a long, brutal battle against the Japanese forces dug in on the island. It was a critical piece of geography for the Allies, as they made their way toward the Japanese mainland.

Bush now remembers shouting at one of the Marines to tell their landing-craft driver, “Slow down! We don't have to be the first onshore!” Getting ashore, however, wasn't the problem. Gordon Larsen, the man who made me laugh when he fixed our furnace, was an eighteen-year-old Marine on Okinawa and he recalls that landing day was the first of April. As he says, “I thought it was an April Fool's joke. There were no Japanese to fight us.”

The main Japanese force had retreated from the advance to the south end of the island, where they were well armed and holed up in caves, prepared to make this a very costly campaign for the invaders. As the Americans moved south toward the Japanese positions, the fighting became so fierce and so unrelenting that it has a special place in the storied history of the U.S. Marines.

Thirty-two days into the campaign to take control of Okinawa, on May 2, 1945, Bob Bush was attached to a rifle company of Marines on the attack over a ridge against heavily fortified Japanese positions. Bush was constantly on the move, going from one downed Marine to another to patch them up and get them evacuated.

Then he was called to help a Marine officer gravely wounded and lying in the open on a ridgetop. Bush didn't hesitate. He went directly to the officer's side and began administering plasma just as the Japanese attacked the position. His Medal of Honor citation describes what followed:

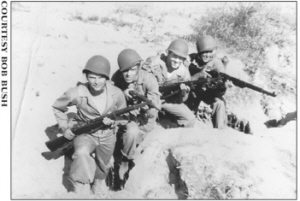

Bob Bush, wartime portrait

Bob Bush and company

In this perilously exposed position, he [Bush] resolutely maintained the flow of life-giving plasma. With the bottle held high in one hand, Petty Officer Bush drew his pistol with the other and fired into the enemy ranks until his ammunition was expended. Quickly seizing a discarded carbine, he trained his fire on the Japanese charging point-blank over the hill, accounting for [the deaths of] six of the enemy despite his own serious wounds and the loss of one eye suffered during the desperate defense of the helpless man.

Bush finally drove off the Japanese and made arrangements for the evacuation of the Marine officer. He refused aid for himself until he collapsed from his wounds as he walked off the ridgetop. More than a half century later, he told me in a cheerful tone, “I remember thinking as the Japanese were attacking, âWell, they may nail me but I'm going to make them pay the price.' ”

Bush was shipped to Hawaii for treatment of his injuries and as soon as he was patched up, he was sent home. He'd been in the service just one year, six months, and twenty-two days but he'd seen enough of war to last a lifetime. He'd earned his right to get on with his life. As the Navy plane carrying him back passed over the Golden Gate Bridge, Bob Bush made a pledge to himself. “I was going to put everything west of there behind me. I was eighteen. I had to get back to school in the fall. I had the girlfriend back home in Washington.” He knew a lot of young men were interested in Wanda and he wanted to get back to win her hand.

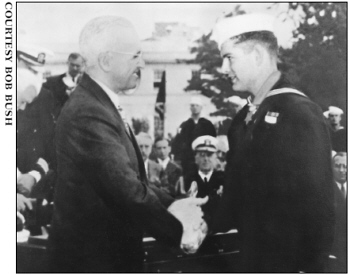

Wanda Spooner, a petite beauty, was eighteen as well when they were married that summer. She quickly got a notion of what life would be like with the charming and ambitious young hero back from the war and ready to take on the world. Their honeymoon was the long cross-country train ride to Washington, D.C., where Bob was to receive his Medal of Honor from Harry Truman, who had been president just a few months, following the death of Franklin Roosevelt.

Suddenly, these two love-struck teenagers were on the south lawn of the White House, surrounded by the president, his cabinet, and the legendary military leaders of the day. Wanda was getting a lot of attention from the generals and the admirals, and one of the White House organizers told Bob as they went on to a reception at the Mayflower Hotel in Washington, “Don't worry about Wanda. The admiral will keep his eye on her.” Bob recalls saying, “Yeah, but who's going to keep an eye on the admiral?”

Bob Bush shaking hands with President Harry S Truman

Bob Bush on the job

Wanda was excited because after the Washington ceremonies they were scheduled to go to New York for a parade and an all-expenses-paid tour of the Big Apple. “But Bob told me we were skipping that. We had to go back home so he could finish his schooling and get on with his business plans.” A frivolous weekend in New York, however tempting, just was not in Bob Bush's plan for life.

Once back in the Northwest, Bob finished his high school requirements, enrolled in a few business classes at the University of Washington, and talked to his friend Victor Druzianich, another veteran, about buying a small lumberyard. Bob figured that with all of the veterans coming home it could be a promising business.

They named their company Bayview and they were off to a fast start in southwest Washington, buying lumber directly from the many sawmills in their area and selling it to contractors and the growing number of homeowners with money to remodel or expand. In fact, business was so good they were working seven days a week and figured they could prosper even more if they could somehow add an extra day.

They had learned in their military training how long they could go without sleep and still function, so they developed a plan. Every other week one of the partners would work a full twenty-four-hour day, driving through the night to Portland to pick up an extra truck-load of lumber. That demanding schedule went on for seven years.

It was the essence of one of Bob's favorite expressions: “Everyone should learn the meaning of that famous little four-letter wordâ

work.

” He also lived by the credo of his favorite high school football coach: “Practice as you play.” To Bob Bush that meant pursuing his business goals full-time, all the time. It was the rigorous schedule pursued by so many World War II veterans. In the service they had learned the importance of identifying an objective and pursuing it until the mission was accomplished. Also, they felt they had to make up for lost time. These were children of the Depression, with fresh memories of deprivation, and the postwar years were abundant with opportunities to make real money. They didn't want to miss out.

At home, Wanda was in charge of raising the familyâthree boys and a girl. They later lost one of their sons in a car accident. The surviving children, Mick, Rick, and Susan, say Bob was often an absentee father, but he would tell them he was working so hard to make their lives better than his had been. Now that they have their own grown-up responsibilities they have a better understanding, but the boys still point out that their dad missed a lot of their Friday-night football games.

Summer vacations often consisted of Bob's dropping the family at a cabin on a lake and then returning to work.

Bob also put the children to work in the rapidly expanding Bayview business empire at an early age. Mick laughs now when he says, “If I put my kids in the situation he put us in, I'd be in jail.” As soon as they were teenagers the boys were learning to drive forklifts and trucks in the lumberyards. Susan was always Daddy's little girl to Bob, but he didn't spare her his favorite four-letter word, either. As a teenager she had to work cleaning the toilets and other public facilities in the stores.

Wanda was the indulgent parent. She was up before everyone in the morning to get breakfast on the table, pack the school lunches, do the laundry, and act as the court of last resort if Bob refused to back down from “no,” his favorite initial response to most requests. That division of family responsibility and the lines of authority were not unusual in the households of veterans across the country.

There were moments of tension in the Bush family, but Wanda smoothed them over and, besides, the kids were the beneficiaries of Bob's wartime heroics. He almost never talked about those awful days on Okinawa, but he belonged to an elite club and the family would be visited by other Congressional Medal of Honor winners, including the famous flier Jimmy Doolittle or the Marine Corps ace Joe Foss, later the first commissioner of the American Football League.