Too Good to Be True: The Colossal Book of Urban Legends (21 page)

Read Too Good to Be True: The Colossal Book of Urban Legends Online

Authors: Jan Harold Harold Brunvand

“The Ski Accident”

M

arch 11, 1987

The Grapevine

Grapevine hears it all, as evidenced by this story about a few couples from DeKalb who were skiing recently in Colorado. While on the slopes, one of the ladies had to use the facilities. There weren’t any close by, so she tried the woods. Unfortunately for her, she had her skis on and, as a result, began to slide down the hill with her pants down. Even more unfortunately, she crashed and was slightly injured. At the ski patrol station where she was getting medical attention for bruised ribs, she began to talk to a male skier who had just been brought in on a stretcher with a leg injury. When she inquired about his mishap, he told her that he had fallen out of a chair lift while watching some crazy woman skiing down the mountain with no pants on. Fortunately, he did not recognize our heroine with her clothes in place. She swore her friends to utmost secrecy about this embarrassing incident, and of course, they honored her request. Right!

A

pril 8, 1987

The Grapevine

Olle Johanssen

In the “grape on our face” department,

The MidWeek

joins the ranks of the

Akron (Ohio) Beacon Journal,

the

Atlantic [sic] Constitution,

the

Montreal Gazette

and the Swedish newspaper

Sundsvalls Tidning

in being duped by the ski accident story. Like our notable counterparts, we were convinced our story in last month’s Grapevine was true. We heard it from several unrelated sources, and although names were never attached, it seemed too funny to ignore. But thanks to an astute and obviously well-read reader, we discovered that the story is part of urban America’s folklore as detailed in the book

The Mexican Pet

by Jan Brunvand (W. W. Norton & Co., 1986), which is available at the DeKalb Public Library. Brunvand said he first heard “this hilarious accident legend” in 1979–80 in connection with a Utah ski resort and later uncovered similar versions retold in newspapers and by word-of-mouth world-wide. The book jacket says Brunvand is one of America’s leading folklorists who has written four books on the subject. We’ll make sure he knows the legend made it to DeKalb too, so he can include our name in his next book.

Sent to me by Sharon Emanuelson, editor of the

MidWeek

of DeKalb, Iowa. “The Ski Accident” first got into print in 1982 and has been revived annually during the ski season. It’s a favorite story used to introduce speakers or warm up audiences at banquets, especially those held at or near ski resorts. Kent Ward, columnist for the

Bangor (Maine) Daily News,

was one of the first to publish the story—on February 13, 1982—and, after numerous requests, he yielded to “droves of discriminating readers” and reprinted it in his column of February 8, 1992. Often the male victim is a ski instructor or patroller, and sometimes the two skiers meet in the bar, both hobbling on crutches or swathed in bandages. The story was told in New Zealand ski resorts as long ago as 1985, and on July 4, 1992, it was reported in the English journal the

Spectator

as the adventure of a British skier in Switzerland, but on August 29 the letters column identified it as an urban legend and “too good to be true.”

“The Barrel of Bricks”

I

am writing in response to your request for additional information. In block number 3 of the accident reporting form, I put “Trying to do the job alone,” as the cause of my accident. You said in your letter that I should explain more fully, and I trust that the following details will be sufficient.

I am a brick layer by trade. On the date of the accident, I was working alone on the roof of a new six story building. When I completed my work, I discovered that I had about 500 pounds of brick left over. Rather than carry the bricks down by hand, I decided to lower them in a barrel by using a pulley which fortunately was attached to the side of the building, at the sixth floor.

Securing the rope at ground level, I went up to the roof, swung the barrel out, and loaded the brick into it. Then I went back to the ground and untied the rope, holding it tightly to insure the slow descent of the 500 pounds of brick. You will note in block number eleven of the accident report form that I weigh 135 pounds.

Due to my surprise to being jerked off the ground so suddenly I lost my pressence of mind and forgot to let go of the rope. Needless to say, I proceeded at a rather rapid rate up the side of the building.

In the vicinity of the third floor, I met the barrel coming down. This explains the fractured skull and broken collarbone.

Slowed only slightly, I continued my rapid ascent, not stopping until the fingers of my right hand were two-knuckles deep into the pulley.

Fortunately, by this time I had regained my pressence of mind and was able to hold tightly to the rope in spite of my pain.

At approximately the same time, however, the barrel of bricks hit the ground and the bottom fell out of the barrel. Devoid of the weight of the bricks, the barrel now weighs approximately fifty pounds.

I refer you again to my weight in block eleven. As you might imagine, I began a rapid descent down the side of the building.

In the vicinity of the third floor, I met the barrel coming up. This accounts for the two fractured ankles and the lacerations of my legs and lower body. The encounter with the barrel slowed me enough to lesson my injuries when I fell onto the pile of bricks and fortunately, only three vertebrae were cracked. I am sorry to report, however, that as I lay there on the bricks—in pain—unable to stand, and watching the empty barrel swinging six stories above me—I again lost pressence of mind—and—let go of the rope. The empty barrel weighted more than the rope so it came back down on me and broke my legs. I hope I have furnished this information you require as how the accident occurred.

Quoted verbatim from a faded, undated sheet produced on a dot-matrix printer and distributed in a San Antonio, Texas, insurance company. “The Barrel of Bricks”—one of the most-often reproduced pieces of typescript lore—has also been presented as a stage monologue and an oral announcement, in song and poetic form, as a cartoon, and in countless handwritten and printed copies distributed in person, on bulletin boards, via fax, and as E-mail. Some versions are organized with numbered points as a formal memo or report and may conclude, “I respectively request sick leave.” Besides insurance companies, this item has circulated in the military and in such trades as building construction, oil drilling, manufacturing plants, radio-tower erection, and even among collectors of old glass insulators for telephone poles. The American comedian Fred Allen turned it into a radio skit popular in the 1930s and ’40s, while the British humorist Gerard Hoffnung delivered his version from the stage and in recordings during the 1950s. The Down East humorists “Bert and I” recorded it in 1961. In 1966 a version purporting to be from a native workman employed by the U.S. Army in Vietnam was widely published, both in newspapers and in such periodicals as

Playboy, Games,

and

National Lampoon.

The song renditions of “The Barrel of Bricks”—titled either “Dear Boss” or “Why Paddy’s Not at Work Today”—have been performed and recorded by numerous “folk” and popular singers. A short version of the story in Irish dialect appeared in a 1918 joke book published in Pittsburgh, and some later treatments have preserved the ethnic stereotype; for example, a fake memo from Bethlehem Steel in 1984 gave two participant’s names as “Vito Luciano” and “Geovani Spagattini.” Cowboy poet Waddie Mitchell’s versified version, involving a whiskey barrel full of horseshoes, was published in

Mother Earth News,

January/February 1990. In

Curses! Broiled Again!

I furnish a detailed debunking of a version alleged to have been written by a Jewish Revolutionary War corporal to General Washington in 1776. Perhaps the ancestor of all of these stories is a traditional European folktale in which a wolf and two animals descend or arise from a well in two buckets strung at either end of a long rope hung over a pulley.

“Up a Tree”

F

austin in waggish mood early in the morning was transformed into Faustin the somber by the evening. He had heard news from the Côte d’Azur, which he told to us with a terrible relish. There had been a forest fire near Grasse, and the Canadair planes had been called out. These operated like pelicans, flying out to sea and scooping up a cargo of water to drop on the flames inland. According to Faustin, one of the planes had scooped up a swimmer and dropped him into the fire, where he had been

carbonisé.

Curiously, there was no mention of the tragedy in

Le Provençal,

and we asked a friend if he had heard anything about it. He looked at us and shook his head. “It’s the old August story,” he said. “Every time there’s a fire someone starts a rumor like that. Last year they said a water-skier had been picked up. Next year it could be a doorman at the Negresco in Nice. Faustin was pulling your leg.”

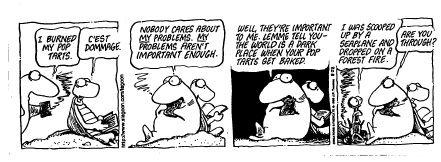

Reprinted with special permission of King Features Syndicate

From Peter Mayle’s popular book

A Year in Provence,

published in 1989. A version involving a scuba diver’s charred body found in a fire-blackened tree circulated in 1987 and ’88 with the locale specified as either the United States or Australia. The legend was suddenly revived in 1996 and discussed in newspapers and on the Internet as an incident that had supposedly occurred recently in Alaska, Oregon, California, or Mexico. An official from Canadair, the company that makes fire-fighting tanker planes, told Don Bishoff, a newspaper columnist in Eugene, Oregon, that this story is “very prevalent in France, Spain, Italy, Greece, even Yugoslavia,” all places where Canadair fire-fighting planes have been dispatched. He also assured Bishoff that the water intakes on these planes, as well as on fire-fighting helicopters, are far too small to scoop up a person.

“The Last Kiss”

T

his story was told to me when I worked for the Santa Fe railroad in Los Angeles back in the early ’70s.

Being “coupled-up” means being caught between the couplers of two freight cars as they come together. This supposedly happened to a young brakeman on the night shift, and he lived for a time after the accident, so his supervisor called his wife, and she came and kissed him one last time as he stood between the two cars.

Then, as the train crew was about to pull the cars apart, the man said, “Wait!” He requested a lantern, and he himself gave the signal to the locomotive engineer to reverse. So the cars separated, and the man toppled over dead. The idea was that, although the couplers had crushed his vital organs, they also held him together long enough for the man to see his wife one last time.

The bit about the lantern is a touch of bravado showing how tough and enduring railroad men can be. It is almost certainly a fictional story since the accident described would be almost instantly fatal. Also, the width of a freight car is such that a person so trapped would have a great deal of difficulty in making his signal visible to an engineer on straight track. (A flat car without a load would be an exception.) But the story was related to me as fact.

Told to me in 1990 by a retired railroad worker. Several other American railroaders sent me the same story, always set on a different line and in another state. In some versions a priest is sent for to administer last rites, and sometimes the dying man dictates his last will and testament to a lawyer. “The Last Kiss” is also told in the military services, usually involving an accident with a heavy vehicle, such as an armored personnel carrier, which overturns; the man stays alive until they turn the vehicle back over again, and sometimes he smokes one last cigarette before dying. As told to U.S. Army troops in Germany in the mid-1980s, a general had a field telephone patched to the civilian telephone system so the man could speak to his wife back in the States one last time. I heard “The Last Kiss” told in New Zealand concerning an accident in a large rock-crushing machine, and in Utah about an accident in a steel-rolling mill. Richard M. Dorson in his 1981 book,

Land of the Millrats,

quotes a harrowing account of “The Man Who Was Coupled” from the northern Indiana steel-making district. In this version a telephone is hooked to a radio so the man can call his wife, but the conversation gets picked up by the plant’s loudspeakers, and all of the other workers stop work to listen to the tragedy unfold. In his 1991 book,

The Soul of a Cop,

Paul Ragonese, “the most highly decorated police officer in New York City history,” gives a firsthand account of an actual “Last Kiss” accident. In September 1982, Ragonese responded to an accident call at the Grand Army Plaza subway station in Park Slope, Brooklyn; a man was squeezed at waist level in the two-inch space between a train car and the platform. While waiting for equipment to extricate him, the police ran a telephone line to the victim, a Vietnam veteran, so he could talk to his wife. He told her that he loved her, did not reveal his predicament, and ended the conversation with “a kissing sound into the phone.” Then he smoked a last cigarette. Seconds after the train car was moved, the man died. Another policeman held a body bag below him to catch the lower half of the man’s body as it fell.