Too Good to Be True: The Colossal Book of Urban Legends (22 page)

Read Too Good to Be True: The Colossal Book of Urban Legends Online

Authors: Jan Harold Harold Brunvand

“The Death of Little Mikey”

1. Have you ever heard any rumors or stories about the cute little kid named “Mikey” who appeared on the LIFE Cereal commercial?

Yeah, poor kid. I heard he OD’d on them. You see, he was working terribly long hours on those cute little LIFE Cereal commercials. He drank lots of pop to keep awake. He was also snacking on Pop Rocks candy. When the two got together inside his body, they exploded. I hear it killed him.

2. When, where, and from whom did you hear this?

In 1979, I think, at school, from friends. The year may be wrong. The introduction of Pop Rocks to our society was not exactly a major event in my life.

Response of an 18-year-old female student from Michigan in 1982 to a survey about “Little Mikey” and Pop Rocks stories made by student Randall Jacobs of Goshen College, Indiana, for a folklore class taught by Professor Ervin Beck. Pop Rocks, a General Foods fruit-flavored “Action Candy” that effervesced in the mouth with what the company described as “a carbonated fizz,” sold in phenomenal quantities after being introduced in 1974. However, rumors that the candies, eaten along with soda pop, had exploded in a child’s stomach led the company to take direct action in 1979 to counter the stories. General Foods ran full-page ads in many American newspapers and eventually withdrew the product. The long-running “Little Mikey” television commercials for the Quaker Oats Company’s LIFE Cereal first aired in 1971, when actor John Gilchrist, who played Mikey, was just 3 1/2 years old. Gilchrist did not speak in the commercial, but his two brothers—parts played in the commercial by his actual older brothers—offered the cereal to the youngster, saying, “He won’t eat it. He hates everything.” The key line in the commercial, after Mikey enthusiastically started eating the cereal, was, “Hey Mikey! He likes it!” The Pop Rocks rumor quickly attached itself to the “Mikey” character, although neither company ever mentioned the other in its advertising or press releases. Pop Rocks candy was reintroduced in 1989, but so far no further rumors or legends have sprung from that product.

You’ve just enjoyed

dinner with a friend in a nice restaurant and, after paying the bill, you reach toward the bowl of mints standing on the counter next to the cash register. “Don’t eat one of those!” your dining companion gasps. “Don’t you know that one of the main ingredients in those mints is

urine?”

That’s certainly enough to stop you in mid-reach; outside the restaurant your friend explains: “They did a study on this and found that 80 percent of men who use the toilet in restaurants don’t wash their hands afterwards. So when these men pick up mints, they leave traces of urine on the other mints, and it really adds up after a while.” Who’s the “they” who studied male hand-washing and mint-grabbing behavior? It’s not explained, but the rumor puts you off restaurant mints forever.

This may remind you of the Great Corona Beer Scare of 1987. That was the year that the bright yellow Mexican-import brew sold in the clear bottle was rumored to be contaminated with urine by disgruntled, underpaid brewery workers. It was also the year that Corona was peaking as a fashionable brew. Bummer. But again, who was the “they” who had discovered this terrible trade secret, and where was the scientific report to back the rumors of anything from 2 to 22 percent urine per batch?

Helping to debunk the story was Fredrick Koenig, a professor of social psychology at Tulane University, who while attending an August 1987 convention in Chicago was cornered by reporters. Koenig, author of the 1985 book

Rumor in the Marketplace,

had his picture taken by the

Chicago Sun-Times

while sipping a Corona beer and explaining the genesis and growth of such unsavory canards as this. In essence, his advice to companies plagued by rumors was first to try waiting them out, since few people believe such stories anyway, and rumors typically are short-lived. But if a story persists, and a company wants to go public, Koenig advised never to repeat the specific terms of the rumor, but instead to stress the positive facts that oppose it. In this instance, it was the documented health and cleanliness standards of Corona breweries that combatted the rumor. In truth, as another newspaper reported the story, these rumors were completely unfounded; thus, if you are a beer drinker, “urine no danger.” (That was the newspaper’s pun, not mine.)

The Corona rumor behaved just like the textbooks said it should: the story was dead by the end of the year, and it developed just a few variable details, such as that the company had been unmasked on TV’s

60 Minutes

(or

20/20

), and that the label contained a confession of the pee-factor, but written in Spanish. Not true, as numerous published reports in 1987 asserted. You heard it here last.

The biggest companies are often the specific targets of contamination rumors and legends, and, although their business may slump for a time, they can usually withstand the whispered assault. McDonald’s, for example, lived through the false stories during the late 1970s of worms, kangaroo meat, or cancerous cows supposedly being ground up for Big Macs. Smaller companies, like the makers of various soda drinks, including Mistic, Tropical Fantasy, A-Treat, and Top Pop, suffered a much higher percentage of loss, and some were even forced out of business. These particular victims of 1990s rumors were said to have included a secret ingredient that rendered black males sterile, a story that also fastened itself onto Church’s Chicken.

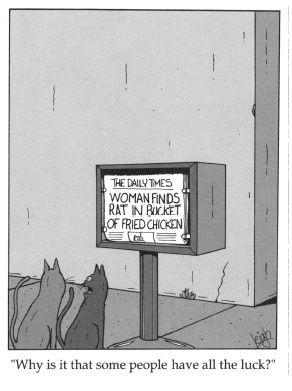

Speaking of chicken tales, here’s a particularly vivid creepy contamination story from the letters column of the September/October issue of

Spy

magazine:

I decided never again to dine on poultry after I heard a strange story in Chicago last weekend.

A young woman ordered a broiled chicken sandwich from a fast-food joint, sans the mayo. Driving along in her car she took a bite out of the sandwich, only to discover that they had included the mayo after all. A dedicated dieter, she immediately threw the sandwich back in the bag and continued to drive.

Later that evening, she checked herself into a local hospital, violently ill with food poisoning. Examination of the broiler found that the chicken contained a tumor and that the substance she mistook for mayonnaise was actually pus from the tumor.

I love that story! Not only does it echo features of “The Kentucky Fried Rat” (see below), but it manages to revive a detail of the famous “Tumor in the Whale” legends of wartime Britain. And

Spy

got it just right in its reply:

First of all, congratulations on the most disgusting letter of the month. But, come on! That’s an urban legend if we ever heard one. Isn’t it?

I found a suspicious contamination story in another published letter, this time written to the Lands’ End company by a reader from Palos Hills, Illinois, and printed in the 1988 Christmas catalog:

Last summer I was visiting some relatives when I accepted an invitation to ride on a combine which was harvesting wheat. Somewhere in the field I lost my Lands’ End mesh knit shirt. (Unknown to me at the time, it had been picked by the combine.)

Six months later, I purchased a loaf of bread at a Chicago area supermarket. Imagine my surprise when I found my undamaged shirt in the loaf of bread! The rugged mesh knit had survived the searing heat of the oven and the razor-sharp blades of the automatic slicer.

I am convinced your knit shirts are perfect for a weekend trip to the farm or for loafing around Chicago.

Although this story sounds like a tall tale, complete with a punning punch line, it actually borrows from a contamination legend. The item usually found inside a loaf of bread in legends is a rodent. Folklorists call this story “The Rat in the Rye Bread.”

Of course, mice and other vermin

do

get into food, even in the best-regulated kitchens. It’s the reality of the situation that makes the folklorized legends so believable. (Ironically, I interrupted the writing of this very chapter to set traps to catch a persistent mouse in our kitchen. Turned out to be

mice,

and we got several!) Nebraska folklorist Roger Welsch, writing about pioneer foodways, described the strategy used by one Plains housewife who found a mouse in her butter churn. Wishing to serve her family “unmoused” butter, she offered to trade her own butter at a local grocery store for someone else’s. “The grocer agreed,” Welsch wrote, then he “took her butter to the back room, trimmed it, stamped it with his mark, took it back out to the counter, and gave it back to the woman as her trade.”

“Moused” food also shows up as a traditional prank. A review in the June 30, 1986, issue of

Time

of a biography of George Herriman (1881–1944), creator of the “Krazy Kat” comic strip that ran from 1913 to 1944, contains this detail:

[Herriman] had two early loves: language and practical jokes. The verbal agility could be practiced alone; the gags needed victims. After George had salted the doughnuts in his father’s Los Angeles bakery and then buried a dead mouse in a loaf of bread, he was informed that if he sought a career away from home, no one would stand in his way.

Not all contaminants are rodents, nor are all contaminees food items. The stories in this chapter provide a nice tasty selection of all kinds of creepy contamination legends.

Bon appétit!

“Fingered by a Dry Cleaner”

A man eating in a Chinese restaurant bit into something too hard to chew or swallow. Rather than causing a scene, he held a napkin to his mouth, removed the offending morsel, wrapped it in the napkin, and put it into his jacket pocket.

After dinner the tough morsel was forgotten, until one afternoon when the man heard a knock at his front door. It was his friendly neighborhood cleaner, accompanied by two police officers. “That’s him,” declared the cleaner.

The policemen produced the jacket and asked the man to identify it. He easily did so, and asked, “What’s wrong, officer?”

One of the police officers showed him an evidence bag in which was the shriveled first two joints of a forefinger. It had been found wrapped in a napkin in the man’s pocket.

“Where’s the rest of the body?” demanded the police, and the man told them where to look.

The good news was that a cook at the restaurant had lost only a finger. The bad news was that a pathologist’s report had already found the finger to be leprous.

“The Kentucky Fried Rat”

I

s there any truth to this story? I heard it in California in 1970 from a friend’s mother, who claims she knew the people it happened to.

A couple went to the drive-in movies and took a bucket of Kentucky Fried Chicken with them. During the movie, they ate the chicken and the girl complained that it tasted funny. Finally, her boyfriend turned on the light in the car and saw that she was eating a fried rat which apparently had gotten into the chicken and was cooked along with it.

T

here was a wife who didn’t have anything ready for supper for her husband. So she quick got a basket of chicken and tried to make her dinner look fancy with the preprepared chicken. Thus, she fixed a candlelight dinner, etc. When her and her husband started eating the chicken, they thought it tasted funny. Soon to find out it was a fried rat.

By permission of Leigh Rubin and Creators Syndicate

M

y sister told me that her friend told her that a lady went to Kentucky Fried Chicken. She was out in the car eating it and noticed that one of the pieces tasted funny. She looked and it had a tail. Then she looked again and saw it had eyes and was a rat. She threw up and went crazy and is in the State [Mental] Hospital in Kalamazoo. She won’t eat any food.

The first story comes from a reader’s query. The second and third are from Gary Alan Fine’s chapter “The Kentucky Fried Rat: Legends and Modern Society” in his 1992 book,

Manufacturing Tales.

Fine’s first version came from a Central Michigan University female, age 24, in 1976; his second from a University of Minnesota female, age 19, in 1977. These variants illustrate the flexible nature of the

legend,

as opposed to the many

lawsuits

based on actual rodents or rodent parts served in food. The legends are anonymous—though sometimes specific as to locale—attributed to a FOAF, short, pointed, and ironic; they often suggest an obvious message like “Always check before you bite,” or “Serves her right for not making supper herself!” It’s also notable that the woman in the legends most often gets the batter-fried rat, and that low light is a prerequisite of her dreadful error. The lawsuits, in contrast, as reported in official court proceedings, contain lengthy detailed accounts of specific incidents that are documented by eyewitnesses or even with a sample of the contaminated food. Rodent/food lawsuits have been brought against a great variety of eating establishments, but seldom, if ever, are the tellers of the legends drawing from any personal experience, or even from direct knowledge of a lawsuit. In recent years, when Kentucky Fried Chicken outlets were opened in Australia and New Zealand, a local variation of the story developed. A man came into a takeout franchise and slung a dead possum onto the counter. In front of a group of horrified customers, he announced, “That’s the last one I’m going to bring you until you pay me for all the others I brought in!”

“The Mouse in the Coke”

W

aiter, there’s a mouse in my Coke!

Have you heard about the guy who found the dead mouse in his Coke? It’s time to set the record straight about this piece of Cokelore.

Many people have read or heard presumably reliable accounts of a mouse that was inadvertently sealed in a bottle of you-know-what. And they wonder: Did a cola-loving customer really tip back a frosty bottle only to discover the little rodent on the bottom—after he’d drained the bottle? And did the victim—sick from the shock, and haunted for life by a fear of cola—really sue the bottler and win hundreds of thousands of dollars in damages?

R. H. of Milwaukee wrote to me recently demanding an explanation for the account of the legend in one of my books. “One of your so-called urban legends isn’t,” R. H. said, in the debunking spirit of a true folklore aficionado. “It’s an actual event or really several—as shown even in courts of law.”