Triumph and Tragedy (The Second World War) (119 page)

Read Triumph and Tragedy (The Second World War) Online

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Thus ended the long struggle in Burma, but a tribute is due to those other Services without whose aid the struggles of the Army would have availed little. The Royal Navy had achieved undisputed command of the sea. They could, and did, convey the Army in safety wherever it was needed. The Allied Air Forces had utterly vanquished the Japanese Triumph and Tragedy

736

planes, and their support had been unfailing. Airborne supply had been developed and maintained on a prodigious scale. Under General Snelling, the chief administrative officer of the Fourteenth Army, the supply services worked admirably. Last, but not least, the Engineers, both British and American, wrought many wonders of improvisation and achievement, such as laying nearly 3000 miles of pipe-line across river, forest, and mountain. The famous Fourteenth Army, under the masterly command of General Slim, fought valiantly, overcame all obstacles, and achieved the seemingly impossible. On May 9 I telegraphed to the Supreme Commander:

Prime

Minister

to

9 May 45

Admiral Mountbatten

(Southeast Asia)

I send you my most heartfelt congratulations upon

the culminating victory at Rangoon of your Burma

campaigns. The hard fighting at Imphal and Kohima in

1944 prepared the way for the brilliant operations,

conducted over a vast range of territory, which have

crowned the exertions of the Southeast Asia Command

in 1945. When these matters were considered at

Quebec last September it was thought both by your

High Command and by the Combined Chiefs of Staff,

reporting to the President and me, that about six British

and British-Indian divisions, together with much

shipping and landing vessels, all of which, and more,

were asked for by you, would be required for

enterprises less far-reaching than those you and your

gallant forces and Allies have in fact accomplished. The

prolongation of the German war made it impossible to

send the British and British-Indian divisions which you

needed, and a good many other units on which you

were counting had to be retained in the decisive

European theatre. In spite of this diminution and

disappointment you and your men have done all and

more than your directive required. Pray convey to

everyone under your command or associated with you

Triumph and Tragedy

737

the sense of admiration and gratitude felt by all at home

at the splendid close of the Burma campaign.

In honour of these great deeds of Southeast Asia

Command His Majesty the King has commanded that a

special decoration, the “Burma Star,” should be struck,

and the ribbons will be flown out to you at the earliest

moment.

The struggle in the Pacific moved no less swiftly to its climax.

3

We had promised at Quebec to send British forces of all arms to the Far East as soon as Germany was defeated, and on my return to London I stated in the House of Commons that the United States had accepted our offer of a fleet. Our effort on land and in the air would only be limited by the available shipping, and plans went ahead accordingly.

In December 1944 Admiral Fraser arrived in Sydney with his flag in the battleship

Howe.

For the first time our main Fleet was to deploy in the Pacific, and under the operational control of an American officer. Our chief difficulties were supply and maintenance. In three years of fighting, the Americans had built up an immense supply organisation and a network of island bases. We could not hope to match this achievement, but it was essential that our Fleet should not wholly depend on our Allies for logistic support.

We had been studying the problem throughout 1944. A mission had been sent in June to consult the Australian Government about establishing a base, but Australia’s manpower was already fully engaged in General MacArthur’s campaigns and in supplying both themselves and the Americans, and it was evident that much material and skilled labour would have to be found from the United Kingdom. The fine port of Sydney was four thousand miles

Triumph and Tragedy

738

from the fighting. To serve the Fleet we needed a train of fuel and store ships, depot and repair ships, hospital ships, and many other types, and huge supplies would have to be transported from the British Isles. This naturally raised misgivings in the mind of Lord Leathers, the Minister of War Transport, but plans were made, the first essentials were provided, and expansion was still going on when the war ended.

Soon after his arrival Admiral Fraser went by air to visit both General MacArthur and Admiral Nimitz. He, and later the Fleet, were most cordially received, and from the outset there grew up a spirit of comradeship which overcame all difficulties and led to the most intimate co-operation at all levels. A message from Admiral Nimitz ran:

The British force will greatly increase our striking

power and demonstrate our unity of purpose against

Japan. The United States Pacific Fleet welcomes you.

Admiral Fraser’s seniority however made it difficult for him to command afloat, where he would have outranked Nimitz’s immediate subordinates. Vice-Admiral Rawlings, who had a distinguished fighting record in the Mediterranean, had accordingly been selected as second-in-command and to command at sea. Early in February 1945

he reached Australia with the main Fleet, many of whose ships had for some time been operating in the Indian Ocean. By the beginning of March the Fleet and the elements of the fleet train were assembled at the American base at Manus Island in the Admiralty Group, and on the 18th it sailed for its first campaign in the Pacific under Admiral Spruance.

Triumph and Tragedy

739

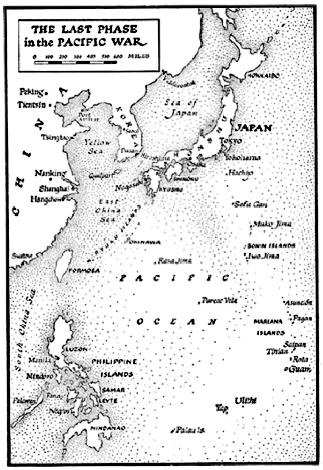

Here much was happening. The time at last had come to strike at the enemy’s homeland. On February 19 Spruance had attacked Iwo Jima, in the Bonin Islands, whence American fighters would be able to escort bombers from the Marianas in attacking Honshu. The struggle was severe and lasted over a month, but victory was won. Meanwhile the British Fleet, now known as Task Force 57, comprising the battleships

King George V

and

Howe,

four fleet carriers mustering nearly 250 aircraft, five cruisers, and eleven destroyers, reached its battle area east of Formosa on March 26. That day its bombers made their first strike at airfields and installations among the islands south of Okinawa. Spruance himself was engaged in full-scale air operations as a prelude to the amphibious attack on Okinawa itself, due to be launched on April 1. On March 18

his fast carrier groups attacked enemy bases near the coast of Japan, and from March 23 they switched to Okinawa.

The task of the British Fleet was to stop the enemy using the airfields in the islands to the south and in Northern Formosa.

From March 26 until April 20 the Fleet, refuelling at sea, continued its mission. Wastage in aircraft and exhaustion of supplies then forced a brief withdrawal to Leyte. The opposition had not been heavy. The

Indefatigable

had been struck by a suicide bomber on April 1, causing casualties, and one destroyer was damaged and had to be withdrawn.

In January, as I have already recounted, we sustained a heavy loss in the death of Lieutenant-General Lumsden. He was my personal liaison officer with General MacArthur, whose confidence he had completely gained. Lumsden’s war record was magnificent. In the very first contacts in Triumph and Tragedy

740

Belgium, when commanding the 12th Lancers, he had brought the armoured car into its own again and had played a distinguished part in the fighting which ended at Dunkirk.

Later he had commanded the 1st Armoured Division in many months of desert warfare. It was for this record that I selected him to serve with General MacArthur, and the reports which he made to me enabled me to comprehend the distant fierce war with all its novel features by which Japan was defeated in the Far East. On January 6 he was standing on the bridge of the

New Mexico,

talking to Admiral Fraser. The Admiral happened by chance to move to the other side of the bridge. A Japanese suicide bomber suddenly swirled down. General Lumsden and Fraser’s aid-decamp were both killed instantly. The pure chance of a casual walk across the bridge saved our Commander-in-Chief.

Triumph and Tragedy

741

Triumph and Tragedy

742

Meanwhile there had been fierce fighting in Okinawa island, and its capture was the largest and most prolonged amphibious operation of the Pacific war. Four American divisions made the first landings. The rugged island provided ample facilities for defence and the Japanese garrison of over a hundred thousand fought desperately.

The whole of Japan’s remaining sea- and air-power was committed. Her last surviving modern battleship, the

Yamato,

supported by cruisers and destroyers, tried to intervene on April 7, but the expedition was intercepted by Spruance’s air carrier fleet and almost annihilated. Only a few destroyers survived.