Troll Fell (4 page)

Authors: Katherine Langrish

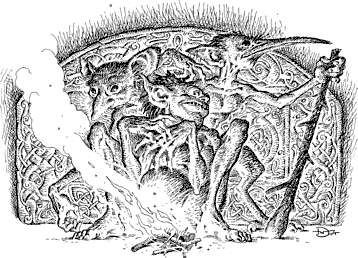

Soot showered into the fire. Alf, the old sheepdog,

pricked his ears uneasily. Up on the roof the troll lay flat

with one large ear unfurled over the smoke hole. Its tail

lashed about like a cat's, and it was growling. But none

of the humans noticed. They were too wrapped up in

the story. Ralf wiped his face, his hand trembling with

remembered excitement and laughed.

“I daren't go home,” he continued. “The trolls would

have torn your mother and Hilde to pieces!”

“What about us?” shouted Sigrid.

“You weren't born, brats,” said Hilde cheerfully. “Go

on, Pa!”

“I had one chance,” said Ralf. “At the tall stone called

the Finger, I turned off the road on to the big ploughed

field above the mill. The pony could go quicker over the soft

ground, you see, but the trolls found it heavy going across

the furrows, and I guess the clay clogged their feet. I got to

the millstream ahead of them, jumped off and dragged the

pony through the water. There was no bridge then. I was

safe! The trolls couldn't follow me over the brook.”

“Were they angry?” asked Sigurd, shivering.

“Spitting like cats and hissing like kettles!” said Ralf.

“They threw stones and clods at me, but it was nearly

daybreak and off they scuttled up the hillside. The pony

and I were spent. I staggered over to the mill and banged

on the door. They were all asleep inside, and as I banged

again and waited I heard â no, I

felt

, through the soles of

my feet, a sort of far-off grating shudder as the top of

Troll Fell sank into its place again.”

He stopped thoughtfully.

“And then?” prompted Hilde.

“The old miller, Grim, threw the door open

swearing. What was I doing there so early, and so on â

and then he saw the golden cup. His eyes nearly came

out on stalks. A minute later he couldn't do enough for

me. He kicked his sons out of bed, made room for me

by the fire, sent his wife running for ale and bread, and

it was âToast your feet, Ralf, and tell us what happened!'”

“And you did!” said Gudrun grimly.

“Yes,” sighed Ralf, “of course I did. I told them

everything.” He turned to Hilde. “Fetch down the cup,

Hilde. Let's look at it again.”

Up on the roof the troll got very excited. It

skirmished round and round the smoke hole, like a dog

trying to see down a burrow. It dug its nails deep into

the sods and leaned over dangerously, trying to get an

upside-down glimpse of the golden goblet which Hilde

lifted from the shelf and carried over to her father.

“Lovely!” Ralf whispered, tilting it. The bowl was wide.

Two handles like serpents looped from the rim to the foot.

The gold shone so richly in the firelight, it looked as if it

could melt over his fingers like butter. Ralf stroked it

gently, but Gudrun tightened her lips and looked away.

“Why don't we ever use it?” asked Sigrid admiringly.

“Use that?” cried Gudrun in horror. “Never! It's real

bad luck, you mark my words. Many a time I've asked

your father to take it back up the hill and leave it. But

he's too stubborn.”

“It's so pretty,” said Sigrid. She stretched out to touch

it, but Gudrun smacked her hand away.

“Gudrun!” Ralf grumbled. “Always worrying! Who'd

believe my story without this cup? My prize, won fair

and square! Bad luck goes to people with bad hearts. We

have nothing to fear.”

“Did the old miller like it?” asked Sigurd.

“Oh yes,” said Ralf seriously. “âTroll treasure!' said old

Grim, âWe could do with a bit of that, couldn't we, boys?'

I began to feel uncomfortable. After all, nobody knew

where I was. I got up to go â and there were the two

boys in front of me, blocking the door, and old Grim

behind me, picking up a log from the woodpile!”

Hilde whistled.

“There I was,” said Ralf, “and there was Grim and his

boys, big lads even then! I do believe there would have

been murder done â if it hadn't been for Bjørn and Arnë

Egilsson who came to the door at that moment with

some barley to grind. Yes, I might have been knocked on

the head for that cup.”

“And that's why the millers hate us?” asked Hilde,

pleased at her success in changing the subject. “Because

you've got the cup and they haven't?”

“There's more to it than that,” said Gudrun. “Old Grim

was crazy to have that cup, or something just like it. He

came round pestering your father to show him the exact

spot on the fell where he saw all this. Wanted to dig his

way into the hill.”

“Old fool!” Ralf growled. “Dig his way into a nest of

trolls?”

“We said no, and wished him good riddance,” said

Gudrun. “But next day he was back. Wanted to buy the

Stonemeadow from your father and dig it up!”

“I turned him down flat,” said Ralf. “âIf there's any

treasure up there,' I told him, âit belongs to the trolls and

they'll be guarding it. I won't sell!'”

“Now that was sense!” said Gudrun. “But what

happened? Next day, old Grim's telling everyone who'll

listen that Ralf's cheated him â taken the money and

kept the land!”

“A dirty lie!” said Ralf, reddening.

“But old Grim's dead now, isn't he?” asked Hilde.

“Oh yes,” said Ralf, “he died last winter. But you

know why, don't you? He hung about on that hill in all

weathers, searching for the way in, and he got caught in

a snowstorm. His two sons went searching for him.”

“I've heard they found him lying under the crag,

clawing at the rocks,” added Gudrun. “Weeping that he'd

found the gate and could hear the gatekeeper laughing

at him from inside the hill! They carried him back to the

mill, but he was too far gone. They blame your father for

his death, of course.”

“That's not fair!” said Hilde.

“It's not fair,” said Gudrun, “but it's the way things

are. Which makes it madness for your father to be

thinking of taking off on a foolhardy voyage and leaving

me to cope with it all.”

Hilde groaned inwardly. Now the quarrel would

begin all over again!

“Ralf,” Gudrun begged. “You know these trips are a

gamble. Ten to one you'll make no profit!”

Ralf scratched his head uncomfortably. “It's not just

for profit,” he tried to explain. “I want â I want some

adventure, Gudrun. All my life I've lived here, in this

little valley. I wantâ” he took a deep breath, “new skies,

new seas, new places!” He looked at her pleadingly.

“Can't you see?”

“All I can see,” Gudrun flashed, “is that you're

throwing good money after bad, for the sake of a selfish

pleasure trip!”

Ralf went scarlet. “If the money worries you, sell

this!” he roared, seizing the golden cup and brandishing

it at her. “It's gold, it will fetch a fine price, and I know

you've always hated it! There's security for you! But I'm

sailing on that longship!”

“You'll drown!” sobbed Gudrun. “And all the time

I'm waiting and waiting for you, you'll be riding over

Hel's bridge with the rest of the dead!”

There was an awful silence. The little ones stared with

big, solemn eyes. Hilde bit her lip. Eirik coughed

nervously and took a cautious spoonful of his cooling

groute. Ralf put the cup quietly down and took Gudrun

by the shoulders. He gave her a little shake and said

gently, “You're a wonderful woman, Gudrun. I married a

grand woman, sure enough. But I've got to take this

chance of going a-Viking!”

A gust of wind buffeted the house. Draughts crept

and moaned through cracks and crannies. Gudrun drew

a deep, shaky breath.

“When do you go?” she asked unsteadily. Ralf looked

down at the floor.

“Tomorrow morning,” he admitted in a low voice.

“I'm sorry, Gudrun. The ship sails tomorrow.”

“

Tomorrow?

” Gudrun's lips whitened. She turned her

face against Ralf 's shoulder and shuddered. “Ralf, Ralf!”

she murmured. “It's no weather for sailors!”

“This will be the last of the spring gales,” Ralf consoled

her.

Up on the roof the troll lost interest in the

conversation. It sat riding the ridge, waving its arms in

the wind, and calling loudly, “Hoooo! Hututututu!”

“How the wind shrieks!” said Gudrun, and she took

the poker and stirred up the fire. A stream of sparks shot

up through the smoke hole. The startled troll threw itself

into a backwards somersault and rolled down off the

roof, landing on its feet in the muddy yard. Then it

prowled inquisitively round the buildings, leaving odd

little eight-toed footprints in the mud. The farmhouse

door had a horseshoe nailed over it. The troll tutted and

muttered, and made a detour around it. But it went on,

prying into every corner of the farmyard, leaving smears

of bad luck, like snail-tracks, on everything it touched.

CHAPTER 3

the Nis

There can't be another Uncle Baldur!

After the first stunned

moment, Peer began to laugh, tight, hiccuping laughter

that hurt his chest. Unable to stop, he bent over the rail

of the cart, gasping in agony.

Uncle Grim and Uncle Baldur were identical twins.

Side by side they strutted up to the cart. He looked

wildly from one to the other. Same barrel chests and

muscular, knotted arms, same thick necks, same mean

little eyes peering from masses of black tangled beard and

hair. One of them was still wrapped up in a wet cloak,

however, while the other seemed to have been eating

supper, for he was holding a knife with a piece of meat

skewered to the point.

“Shut up,” said this one to Peer. “And get down.”

Only the voice was different â deep and rough.

“Now let me guess!” said Peer with mad recklessness.

“Who can you be? Oooh â tricky one! But wait, I've got

it! You're my Uncle Grim! Yes? You

are

alike, aren't you!

Like peas in a pod. Do you ever get muddled up? I'm

yourâ”

“Get down,” growled Uncle Grim, in exactly the

same way as before.

“ânephew, Peer!” Peer finished, impudently. He held

up his wrist, still firmly tethered to the side of the cart,

and waggled his fingers.

Uncle Grim snapped the twine with a contemptuous

jerk. Then he frowned, lifted his knife and squinted at

the point. He sucked the piece of meat off, licked the

blade, and sliced through the string holding Loki. He

stared hard at Peer.

“

Now

get down,” he ordered, through his food. He

turned to his brother as Peer jumped stiffly down. “He's

not much, is he?”

“But he'll do,” grunted Uncle Baldur. “He can start

now. Here, you!” He thrust the lantern at Peer. “Take

this! Put the oxen in the stalls. Put the hens in the barn.

Feed them. Move!” He threw an arm over his brother's

shoulders, and as the two of them slouched away

towards the mill Peer heard Baldur saying, “What's in

the pot? Stew? I'll have some of that!”

The door shut. Peer stood in the mud, the rain

drumming on his head, the lantern shaking in his hand.

All desire to laugh left him. Loki picked himself up out

of the puddle and shook himself wearily. He whined.

Peer drew a deep breath. “All right, Loki. Let's get on

with it, boy!”

Struggling with the wet harness he unhitched the

oxen and led them into their stalls. He tried to rub them

dry with wisps of straw. He unloaded the hens and set

them loose on the barn floor, where an arrogant, black

cockerel and a couple of scrawny females came strutting

to inspect them. He found some corn and scattered it.

By now the stiffness had worn off, but he was damp, cold

and exhausted. The hens found places to roost, clucking

suspiciously. Loki curled up in the straw and fell fast

asleep. Peer decided to leave him there. He hadn't

forgotten what Uncle Baldur had said about his dog

eating Loki, and he certainly had heard a big dog barking

inside the mill. He took up the lantern and set off across

the yard, picking his way through the mud. The storm

was passing, and tatters of cloud blew wildly overhead. It

had stopped raining.

The mill looked black and forbidding. Not a

glimmer of light escaped from the tightly closed shutters.

Peer hoped he hadn't been locked out. His stomach

growled. There was stew inside, waiting for him! But he

stopped at the door, afraid to go in. Did they expect him

to knock? Voices mumbled inside. Were they talking

about him?

He put his head to the door and listened.

“Not worth much!” Baldur was saying.

There was a sort of thump and clink. “Count it

anyway,” said Grim's deep voice, and Peer realised that

Uncle Baldur had thrown a bag of money down. Next

came a muffled, rhythmical chanting. His uncles were

counting the money together. They kept stopping and

cursing and getting it wrong.

“Thirty, thirty-one,” Baldur finished at last. “Lock it

up!” His voice grew fainter, as he moved further from

the door. “We don't want the boy getting his hands

on it.”

Peer clenched his fists. “That's my money, you

thieves!” he whispered furiously. A lid creaked open and

crashed shut. They had hidden his money in some chest,

and if he walked in now, he might see where it was.

“About the lad,” came Baldur's voice. Peer stopped.

He glued his ear to the wet wood. Unfortunately Baldur

seemed to be walking about, for he could hear feet

clumping to and fro, and the words came in snatches.

“â¦time to take him to the Gaffer?” Peer heard, and

something like,“â¦no point in taking him too soon.”

The Gaffer? He said that before, up on the hill

, thought

Peer with an uneasy shiver.

What does it mean?

He strained

his ears again. Rumble, whistle, rumble, went the two

voices. He thought he heard something about “trolls”,

followed quite clearly by: “Plenty of time before the

wedding.” A succession of thuds sounded like both of his

uncles taking their boots off and kicking them across the

room. Finally he heard one of them, Grim it must be, say

loudly, “At least we'll get some work out of him first.”

That seemed to conclude the discussion. Peer

straightened up and scratched his head. A chilly wind

blew round his ears and a fresh rainshower rattled out of

the sky. Inside the mill one of the brothers was saying,

“Hasn't that pesky lad finished

yet

?” Hastily Peer

knocked and lifted the latch.

With a blood-curdling bellow, the most enormous

dog Peer had ever seen launched itself from its place by

the fireside directly at his throat. Huge rows of yellow,

dripping teeth were closing in on his face when Uncle

Grim put out a casual arm and yanked the monster

backwards off its feet, roaring, “Down, Grendel!”

The huge dog cringed. “Come in and shut the door,”

Grim growled roughly to Peer. “Don't stand there like a

fool. Let him smell you. Then he'll know you.”

Nervously Peer held out his hand, expecting the

animal to take it off at the wrist. Grendel stood taller

than a wolf. His coat was brindled, brown and black, and

a thick ruff of coarse fur grew over his shoulders and

down his spine. Hackles up, he lowered his massive head

and smelled Peer's hand as if it were garbage, rumbling

distrustfully. Uncle Grim gave Grendel an affectionate

slap and rubbed him round the jaws. “Who's a good

doggie? Who's a good boy, then?” he cooed admiringly.

Peer wiped a slobbery hand on his trousers. He thought

that Grendel looked a real killer â just the sort of dog the

Grimsson brothers

would

have.

“This dog's a killer,” boasted Uncle Grim, as if he

could read Peer's mind. “Best dog in the valley. Wins

every fight. Not a scratch on him. That's what I call a

proper dog!”

Thank goodness I didn't bring Loki in!

Peer shuddered.

Uncle Grim fussed Grendel, tugging his ears and calling

him a good fellow. Grateful to be ignored, Peer looked

around at his new home.

A sullen fire smouldered in the middle of the room.

Uncle Baldur sat beside it on a stool, guzzling stew from

a bowl in his lap, and toasting his bare feet. His wet socks

steamed on the black hearthstones. He twiddled his vast,

hairy toes over the embers. His long, curved toenails

looked like dirty claws.

The narrow, smoke-stained room was a jumble of

rickety furniture, bins, barrels and old tools. A table,

crumbling with woodworm, leaned against the wall on

tottering legs. Two bunk beds trailed tangles of untidy

blankets on to the floor.

At the far end of the room a short ladder led up to a

kind of loft with a raised platform for the millstones.

Though it was very dark up there, Peer could make out

various looming shapes of mill machinery: hoists and

hoppers, chains and hooks. A huge pair of iron scales

hung from the roof. Swags of rope looped from beam to

beam.

Uncle Baldur belched loudly and put his dish on the

floor for Grendel. Suddenly the room spun around Peer.

Sick and dizzy, he put his hand against the wall for

support, and snatched it quickly away, his palm covered

in grey dust and sticky black cobwebs. Cobwebs clung

everywhere to the walls, loaded with old flour.

Underfoot, the dirt floor felt spongy and damp from a

thick deposit of ancient bran. A sweetish smell of rotten

grain and mouldy flour blended with the stink of Uncle

Baldur's cheesy socks. There was also a lingering odour

of stew.

Peer swallowed queasily. He said faintly, “I did what

you said, Uncle Baldur. I fed the animals and put them

away. Is there â is there any stew?”

“Over there,” his uncle grunted, jerking his head

towards a black iron pot sitting in the embers. Peer took

a look. It was nearly empty.

“But it's all gone,” he said in dismay.

“

All gone?

” Uncle Baldur's face blackened. “

All gone?

This boy's been spoilt, Grim. I can see that. The boy's

been spoilt!”

“There's plenty there,” growled Grim. “Wipe out the

pot with bread and be thankful. Waste not, want not.”

Silently, Peer knelt down. He found a dry heel of

bread and scraped it round inside the pot. There was no

meat left, barely a spoonful of gravy and a few fragments

of onion, but the warm iron pot was comforting to hold,

and he chewed the bread hungrily, saving a crust for

Loki. When he had finished, he looked up and found

Uncle Baldur staring at him broodingly. His uncle's dark

little eyes glittered meanly, and he buried his thick fingers

in his beard and scratched, rasping slowly up and down.

Peer stared back uneasily. His uncle convulsed. He

doubled up, choking, and slapped his knees violently. He

jerked to and fro, snorting for breath. “Ha, ha, ha!” he

gasped. His face turned purple. “Hee, hee! Oh, dear. Oh,

dear me!” He pointed at Peer. “Look at him, Grim! Look

at him! Some might call him a bad bargain, but to me â

to me, he's worth his weight in gold!”

The two brothers howled with laughter. “That's

funny!” Grim roared, punching his brother's shoulder.

“Worth his weight in â oh, very good!”

Peer looked at them darkly. Whatever the joke was, it

was clearly not a nice one. But what was the good of

protesting? It would only make them laugh louder. He

gave a deliberate yawn. “I'm tired, Uncle Baldur. Where

do I sleep?”

“Eh?” Uncle Baldur turned to him, tears of laughter

glistening on his hairy face. He wiped them away and

snorted. “The pipsqueak's

tired

, Grim. He wants to

sleep

.

Where shall we put him?”

“On the floor with the dog?” Peer suggested

sarcastically. The two wide bunks belonged to his uncles,

so he fully expected to be told something of the kind.

But Uncle Grim lumbered to his feet.

“Under the millstones,” he grunted. He tramped

down the room towards the loft ladder, but instead of

climbing it, he burrowed into a corner, kicked aside a

couple of dusty baskets and a broken crate, and revealed

a small wooden door not more than three feet high. Peer

followed him warily. Uncle Grim opened the little door.

It was not a cupboard. Behind it was blackness, a strong

damp smell, and a sound of trickling water.

Before he could protest, Uncle Grim grabbed Peer by

the arm, forced him to his knees and shoved him

through into the dark space beyond. Peer pitched

forwards on to his face. With a flump, a pile of mouldy

sacks landed on his legs. “You can sleep on those!” his

uncle shouted. Peer jerked and kicked to free his legs. He

stopped breathing. His throat closed up. He scrambled to

his feet and hit his head a stunning blow. Stars spangled

the darkness. He felt above him madly. His hands

fumbled along a huge rounded beam of wood and found

the cold blunt teeth of an enormous cogwheel. He

turned desperately. A thin line of light indicated the

closed door. His chest heaved. Air gushed into his lungs.

“

Uncle Baldur!

” Peer screamed. He threw himself at

the door, hammering on it. “Let me

out!

Let me

out!

”

He pounded the door, shrieking, and the rotten catch

gave way. The door swung wide, a magical glimpse of

firelight and safety. Sobbing in relief, Peer crawled out

and leaped to his feet. Uncle Baldur advanced upon him.

“No!” Peer cried. He ducked under Uncle Baldur's

arm and backed up the room, shaking. “Uncle Baldur,

no, don't make me sleep in there. Please! I'll sleep in the

barn with Loki, I'd rather, really!”

“You'll sleep where I tell you to sleep!” Uncle Baldur

reached out for him.

“I'll shout and yell all night!” Peer glared at him

wildly. “You won't sleep a wink!”