Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea (28 page)

Read Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea Online

Authors: Adam Roberts

The sun above him had become only a faint star, casting no illumination. Then he lost sight of it altogether. He was in perfect blackness.

Down and down and down.

How would he know that the air was going bad? Would he begin to hallucinate? Would he last long enough to drift into the ambit of a third sub oceanic sun, with who knows what horrific native fishy monsters circling it like planets in outer space? Surely not! He tried, for a while, breathing shallowly, to conserve such air supply as he had. But then he thought, what is the point in postponing the inevitable? Then he considered simply taking charge of his destiny, putting an end to his physical torment and committing suicide. But something held him back. A residual Catholicism? It hardly mattered. He did not believe that God was here, about to scoop him into his giant hand and press him to his tender breast. That could never be. Whether he acted or did not act was equally irrelevant.

Below him something was glimmering, very faint but definitely there. A monster of the deep? Lebret’s heart began to thud in his breast. The shape loomed closer, acquired definition.

It was a gigantic hand, glowing faintly. It was a hundred metres long –

twice

a hundred metres, the fingers pressed together, reaching beneath him to catch.

Lebret felt a flash of panic. He couldn’t have explained why – except the thought that a human form of titanic proportions (if that was his

hand

, then how big must the

whole body

be!) was somehow here, in this fantastically distant and alien sea – that this entity was reaching out to catch him, Alain Lebret, out of all the morsels falling through the water … Somehow this terrified him.

He began to wriggle, to struggle. It hurt to kick out with his left leg, but he thrashed with his right and crawled at the water with his arms. Perhaps he could swim so as to miss the giant hand.

He was closer to it now. Then, with a rush, he was level with it – it horizoned him, gleaming pink-white, and he landed

upon

it, actually touched down. The substance was hard, but not wholly unyielding; something dense and packed, like coral. Whatever it was, it was not flesh.

Lebret hit the surface like a parachutist reaching the ground. It jarred through his wounded foot, and sent a shock of pain up his spine; but he rolled with the blow and sprawled sideways upon it.

Fear had nested inside Lebret now. He was not acting rationally. You might think he would be grateful to have found a platform – somewhere to stand, instead of continuing to fall through infinite water forever. But he was not thinking in any logical way about his situation. He felt a grip of certainty that the hand was about to fold over, to close into a fist with him in the middle – that it was going to crush him. In that moment such a fate scared him more profoundly than being burnt to death in a suboceanic sun, or devoured by the childranha.

He got to his feet, and ran towards the edge of the hand. It was that comical, slow-motion underwater running – yet, he

did

move, his feet striking the platform below him and gaining a degree of traction. It did not take him long to get to the edge, and then he hurled himself free of the shape, to sink once again through the infinite depths. Better that, than …

Than what?

He did not sink.

The glimmering shape of the gigantic, outstretched hand hovered a couple of metres away and a metre above him. At first he assumed it was falling with him; but the tug in his gut was absent. More, the pain in his jaw was markedly less than it had been.

He floated in the water for a little. Though there was very little light, it was possible to see the underside of the hand. This was enough to see that it wasn’t a hand at all. It was, on the contrary,

a huge conch shell – improbably massive, but recognisably marine, nevertheless.

Cautiously kicking out with his good leg, Lebret swam up through the water. Once he was above the level of the giant spread-out scallop he felt the tug resume, and in a moment he was drawn back down onto the platform.

He stood up, feeling calmer. Regarding it now, he was surprised he had ever thought that this structure was a hand: its fan-shape and the broad, shallow flutes all leading towards its tapering end – all this said ‘shell’ very clearly. Yet it did not appear to be made of shell-stuff. Crouching down, Lebret poked at the substance with his bare fingers. It felt firm, with only a slightly spongy give to it, as if constructed of close-packed fibres. It had a consistency somewhere between stone and plastic.

He stood up again. He felt light-headed. Perhaps his air was finally running out. Perhaps all this was a hallucination – a dying man’s vision. If so, Lebret thought, then I might as well explore it.

He made his way along the length of the gigantic scallop shape, towards its narrow end. The light grew a little brighter, and soon enough he saw why – in at the stem of the giant shell was a circle of light, a metre or so wide. Bending down, he looked into this.

It was a window.

On the far side was a circular corridor leading down, a clean white colour, lit with lamps inset into its walls. There was no ladder, and the corridor stretched many metres before opening out into – Lebret peered, trying to make out – a larger chamber.

He felt around the rim of this window with his fingers, and, as in a dream, found a catch. It pulled easily, and the window slid away. Lebret reached inside, through a wall of standing water and into air.

There seemed little point in delaying. Lebret thrust his head through the hole, out of water and into the air. The rest of his body followed and his sense of up-and-down deserted him. He was floating head down, except that it didn’t feel that way. It felt as if the corridor had swung about. There was plenty of room to bring his legs about, and look back where he had come – the water

was a membrane, bleeding spits and dribbles into the corridor, but otherwise not penetrating. There was a little red-button in by the rim. Lebret pushed this and the window slid back into place.

He pulled off his mask, and sniffed the air cautiously. It seemed breathable. Indeed, it tasted a good deal sweeter than the stuff in his tank.

The pain in his jaw was much reduced; although, as if following some pitiless cosmic logic of the balance of pain, the wounds in his leg and foot seemed sharper and more defined.

He wriggled free of the triple tank, and pressed his wet hair against his scalp. Droplets of water floated all around him.

‘Hello?’ he called, wincing as his jaw complained at the movement. ‘Who is there?’

There was no reply. Well, there was no point in coming this far and then loitering in the corridor. Lebret put his palms on the smooth white sides, pressed with his good foot on the other side, and propelled himself along.

The corridor was longer than it had appeared from outside; but eventually Lebret came to the end, and passed through into a large, bulb-shaped chamber.

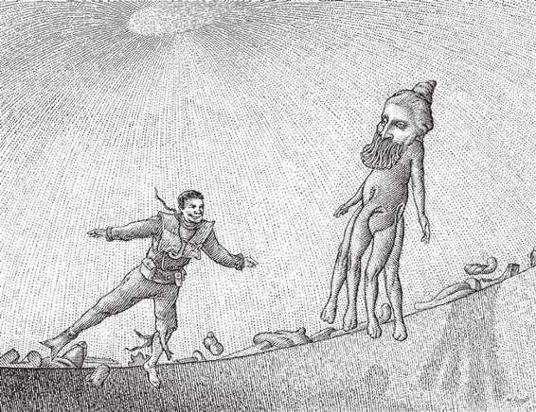

It was approximately the size of a two-storey house, without internal walls or divisions but with shelves, oriented variously, and with diverse items of mechanical or technological cast upon them. The space, like the corridor, was white-coloured and clean; and on the far side a large circular bulge shimmered dark-grey – water, Lebret assumed. But he took hardly any of this in, because the room’s occupant so startled and alarmed him.

That occupant was a human head, three or four times the conventional proportions. So monstrous was this apparition, indeed, that Lebret stared for a long time before registering the entity’s body at all – a regular-sized body, with a plump stomach, but with four legs in addition to the conventional two arms. At the end of each of the four legs was flat and broad appendage, more like a paddle than a human foot.

The being’s face was unmistakably human: dark brown of skin, with a nose so large and pronouncedly aquiline it almost

resembled a shark’s fin. The eyes, though comparatively small in the broad face, were bright and alert. They were old eyes. There was no mistaking that about them. The forehead was smooth and broad, the black hair slicked back into a queue. The oddest thing about this individual – his size aside – was his beard. It looked like a regular beard, although unusually bushy and capacious, the strands of hair coiling and twisting in the zero-gravity of that strange place. But Lebret looked again and saw that the individual strands of the being’s beard were not hair, but rather twisting tentacular filaments, moving not with any random action but purposefully, deliberately. The beard coiled and moved before the strange being’s face.

This person (for I suppose we must call him a person) looked at Lebret. The beard shifted, opening a gap through which a wide mouth and little peg-like, wide-set teeth were visible.

‘My dear fellow,’ said the being, in flawless French. ‘What on earth has happened to

you

?’

‘Dakkar?’ gasped Lebret, feeling woozy.

‘Good gracious, your leg! And your face! What has happened to your face? And where – and where is everybody else?’ He floated towards Lebret, accompanied by little squirting noises. The beard folded its myriad fronds about the mouth. Lebret, unable to prevent himself flinching away, noticed that the tentacles were all covered in tiny beads of water.

‘I’m sorry, Monsieur,’ said Lebret, tears springing in at his eyes. ‘You are too – repulsive to – too repulsive to—’

‘Come!’ insisted Dakkar. His voice was high-pitched, even squeaky, and at odds with the over-sized head through which it emerged. ‘You must have medical attention for your wounds!’

Dakkar led him to the other side of the chamber, and dived into the bubble of water. Lebret was shuddering. There was something unpleasantly insectile about the fellow’s motion – quite apart from his hideous appearance. The urge to flee was strong within him; but where would he go? Back onto the corridor to wear again the breathing apparatus (surely out of air, now) and into the black sea? His leg was raw with pain; at a dozen places his body ached and stung – most of all, he was exhausted.