Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea (25 page)

Read Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea Online

Authors: Adam Roberts

He felt his own face, gingerly. Perhaps the jaw was not actually broken, but it had certainly suffered a potent trauma. The hinge-joint felt tender, and by touch alone Lebret could tell that the right side of his face was much more swollen than the left. The teeth were a different matter; the raw nerve squealed with pain every time he breathed in. The pain would presumably fade, eventually, if only because the nerve had died; but Lebret wondered if it were possible to speed that process up. How does one kill a nerve? Could he, perhaps, reach in and

pinch

it dead? The very thought made him shake with revulsion. Once again he felt his gorge rise.

Still

, he thought,

I’m alive. Against all the odds, and the best efforts of Billiard-Fanon, I am still alive.

He had to decide what to do next. Certainly he couldn’t lurk in this intermediary space between ocean and the submarine’s interior – quite apart from anything else, the air would soon be

used up. But going back into the

Plongeur

remained an unappealing prospect. He could go inside, crawl through to the bridge – but Billiard-Fanon would surely only shoot him again. For a minute or so he pondered the likelihood that Billiard-Fanon had been disarmed and locked in his cabin. Maybe the crew had seen the ensign for the lunatic he was. Perhaps Lebret, were he to reappear, would be greeted joyously, clapped on his shoulder, asked to repeat his incredible story – perhaps given treatment, painkillers, a shot of whisky. This thought made him giddy with hope, but he dismissed it. Illusory. He had to be realistic. Billiard-Fanon had the gun. He was quite mad enough to shoot anybody who challenged him.

No. Going back into the

Plongeur

was not an option. But what else could he do?

His jaw twinged and flared. There was, he decided, only one other possibility. There remained a single diving suit, just on the other side of the inner airlock door. He could take this, swim back along to the breach in the side of the

Plongeur

, and back into the mess. It would be completely flooded by now, of course; but he ought to be able to open the forward hatch and get into the dry forward compartments – if the crazy physics of this place still obtained, he could do so without necessarily letting in too much water. He could get access to the food and drink stowed in the torpedo tubes. And then? Well, then he would have to consider his position.

The pain inside his skull swelled savagely, and slowly fell away from that dolorous intensity. He swore. His thoughts reverted to the strange leviathan that was swimming about the

Plongeur

, and whose gigantic talon had presumably ripped the gigantic hole in the hull. Presumably it was after oxygen, as the cuttlefolk had been. But what if it wanted more? Was it alone? Then, thinking further, Lebret’s thoughts went back to de Chante. What

had

happened to that brave sailor, on his dive to repair the ballast tanks? Had there been some cousin of this leviathan, this alien whale, that had noticed him swimming and had snapped him into its jaws?

Then the whole crazy unreality of the situation he was in fell

upon Lebret’s mind like a landslide. He had started this voyage with only the vaguest intimations that there was anything beneath – or more strictly speaking,

beyond

– the Atlantic. Now he was confronted with the appalling reality of those suspicions. The message had been true. And yet, the truth had been more than he could possibly have imagined, and had cost lives. ‘Including mine, more or less,’ he said aloud, spitting blood. The strange thing was: water droplets from his body rolled through the air in the small space as if blown by a breeze, but his blood fell fell slowly downward.

The pain brought him back – well, not ‘to earth’, but to whatever the equivalent was in that place. He had to think practically.

The only illumination in the airlock space came through the little window set in the internal door. It took Lebret a deal of fumbling about, all the while struggling to ignore the debilitating pain in his face, before he found the release catch. Once it was sprung, he was able to spin the wheel and open the door. He tumbled through into the larger chamber.

Awkwardly he got to his feet. It took him longer than it ought to understand why the room looked wrong, and why he could not locate the cupboard with the diving suit inside it. The whole space had been rotated through ninety-degrees (of course!). The cupboard was part of the floor rather than part of the wall.

Pain stabbed through him. It throbbed, coming and going, but the going was never far enough, and the coming excruciating. Lebret shut his eyes and waited. Finally the agony in his mouth abated, even if only a little. When he opened his eyes, Capot was standing in front of him.

Lebret was surprised to see him; but, judging by the colour of the sailor’s face, not as surprised as Capot was. ‘What—what?’ the young man gasped.

‘Get out,’ said Lebret, without thinking. Blood spattered from his mouth when he spoke. ‘You should get out.’

‘Why?’

A cold anger swelled inside Lebret. ‘Have you seen what is swimming through the waters outside the

Plongeur

?’ His words

were rendered somewhat indistinct by the swelling in the side of his face, and the slick lubrication of blood inside his mouth. ‘Leviathan, larger than earthly whales. Will it swallow us all, whole? Billiard-Fanon called me a Jonah. I suggest he consult the

relevant Biblical passage!’

These last few words were little more than incomprehensible splutters, but they galvanised the terrified-looking Capot. He turned and fled the small space.

He will go and warn Billiard-Fanon, Lebret thought, with a sinking heart. I must work quickly.

He tried to ignore the swelling-withdrawing-swelling agony in his jaw, and brought out the diving suit. Its cold rubbery weight – still wet from its previous wearer – gave it a most unpleasant, flayed-amphibian quality. Lebret’s own clothes were sodden; he removed his shoes, and peeled his socks off with an audible smacking sound. Then he took off his trousers, sweater and shirt and rolled them into a bundle around his shoes. He was shivering, but the cold was not unbearable. The sub oceanic sun must have heated the water to a reasonable temperature. He tied the bundle of clothes to the back of the suit with one of its straps, and then pulled the clammy fabric over his legs. It squeaked, as if in pain. With some difficulty he got his arms and body into it. Finally there was the helmet. Lebret examined it – the design was a little different to the rebreathers he’d been trained on during the war – it had been that long since he’d swum underwater. This design was a full face mask that left his head bare at the back. On the side it said, in small letters,

Air Liquide

. ‘Necessity,’ he told himself, ‘is the best drill instructor.’ He fitted the miniature rubber anvil mouthpiece between his lips, fiddled with the tank, and breathed in.

He would only need it for the ten minutes it would take him to scramble over the top of the sub, into the now-flooded mess, and through into the forward compartments of the

Plongeur

. As to what he would do then – well, he would deal with that problem when it presented itself. It did not do to think too far into the future. After all, there almost certainly

was

no far future for anybody on the

Plongeur

.

He had to hurry. Cabot must have informed Billiard-Fanon of his presence aboard by now. He was surprised the ensign hadn’t come hurrying straight over with his pistol out to finish what he had started.

Lebret fitted himself clumsily back through the airlock, water spraying up through the opening. He pulled the door shut behind him. The outer door opened easily enough, and he squeezed himself out. The added pressure of the water upon his jaw caused the pain to flare. The spike in agony was sharp enough to make him lose concentration; his grip on the edge of the door loosened, and the current – or whatever it was – snatched at his body. Adrenaline skittered through him, and he gripped tight at the lip of metal of the airlock door.

His heart was thudding, but the pain was a little less now. Manoeuvring himself awkwardly he got his feet on the ledge. It did feel, crazily, as if he were standing on a ledge at the top of a tower-block. By all rights, and every law of physics, he ought to be able just to launch himself into the water and swim where he wanted to go. But the invisible sucking current tugged palpably at his legs. Fear gripped him. His teeth sang with pain. Awkwardly, and clinging to the fabric of the submarine, he reached up and put his hand into the intake valve for the airlock chamber.

Pulling himself up was hard, but he was able to bring his left foot high enough up to slip it into the crevice, and from

there

he could push himself up to a place where the slope of the submarine’s hull was less precipitous. He stopped. A powerful twinge rang through his injured jaw, resonating inside his skull. He could feel the action of the water as he swished his arm through it; the resistance and fluidity of it. Only minutes earlier, he had been immersed in it, and nearly drowned. Yet now, inside his suit, it felt as if he were standing on a high curving roof in air; as if the slightest misstep and he could fall. Impossible!

‘Not the first impossible thing,’ he thought to himself. ‘Maybe I need to believe – believe and I will be able to swim.’

He centred himself as best he could, tried to concentrate on what he was doing despite the pain he was in, and resumed

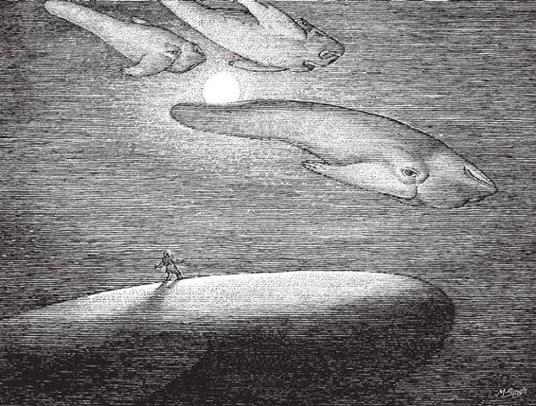

clambering his way up the C-curve. At one point he slipped back a little, but was able to scrabble back up. Eventually, breathing with hisses and clicks, he got to the top of the metal hill. The blue-white light of the sub oceanic sun was bright enough to cast a fuzzy grey shadow. The leviathan seemed to have departed. But, no – looking up, he could still see it – or see

them –

three of the huge beasts. The bubbles, catching the light and glinting like stars against the blacker upper water. The leviathans turned and threaded the faintly glittery zone, like sharks trying to catch sardines.

Lebret breathed out. Bubbles twisted around his faceplate and neck like slugs. Why didn’t they go flying buoyantly upwards? He himself felt the downward tug so forcefully; they ought by the same logic to have sped away upwards. He couldn’t say why they didn’t. He had to wave his hand to clear the mirror-shapes from his line of sight.

But at last he could see the breach in the side of the vessel. Stepping carefully, he started towards it. There were strange tinny pinging sounds inside his ears. His jaw ached terribly.

A shadow passed over him. Looking round he saw that one of the leviathans was looming up at him. Perhaps it had been lurking behind the far side of the

Plongeur

, or maybe it had darted down from the school above them. But Lebret could see what had excited the beast – the trail of air bubbles, stubbornly refusing to zip up and away. The bubbles

were

rising, but much too slowly, and the effect was to lay a sloping trail of bubbles down towards him. Like a line of breadcrumbs.

Lebret quickened his pace, walking across the ‘roof ’ of the

Plongeur’

s external hull, but it was not easy moving through water, and the effort made him breathe more heavily, which in turn squeezed more pain out of his broken mouth. The next thing he knew, his feet were sliding over the metal of the hull. Somebody had punched him in the small of his back. He went over – lying flat, face down, and swooshing feet-first onwards. The great flank of the leviathan swept past him.

The beast’s flipper caught him a second time. With a powerful

throb of pain in his jaw, Lebret spun upside down. He saw the long grey arc of the

Plongeur’

s hull passing away from him, and then he felt the tug in his gut as he started to fall.

A beat too late he understood what was happening. Trying to ignore the agony in his face, he thrashed his arms and legs as forcefully as he could – if only he could swim hard enough, surely he could reach the submarine. But the dark-grey wall of metal slipped past, and disappeared above him, and he was sinking hard into the depths.