Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea (5 page)

Read Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea Online

Authors: Adam Roberts

But the end did not come. Instead, and gradually, the shaking calmed, and the deep buzz of vibration quietened. It was a very long drawn out diminuendo, the noise and the shaking withdrawing itself incrementally until both had almost disappeared. Impossible to believe that the implacable wrath of the ocean was diminishing – it was quite against all the laws of physics.

‘Monsieur Le Petomain,’ said Captain Cloche. ‘What has happened?’

‘I—I cannot say, captain,’ replied the astonished shipman.

‘What is our depth?’

‘Five thousand seven hundred metres, sir, and still descending.’

‘Impossible! The ocean is not so deep! Not at our location, at any rate. We should long since have collided with the continental shelf.’

‘Aye, sir.’

‘Your instrumentation is faulty, sailor.’

‘That may be, Captain,’ conceded Le Petomain. ‘Except that – well, we

are

still descending!’

There was no denying this. The

Plongeur

was still angled sharply forward; the downward motion, shuddery, a little uneven, but still unmistakably downwards, could still be felt in every solar plexus.

‘Sonar?’

‘Nothing, Captain.’

The captain pondered for a moment. ‘The depth

is

consistent with both the rapidity of our descent and the length of time

elapsed,’ he announced. ‘In which case – the only explanation is that we have fallen into some unmapped trench within the ocean floor.’ But then, again like a lion, he shook his shaggy head; a gesture of immense force and emphasis. ‘No!’ he contradicted himself. ‘These are not the south polar seas – or the middle of the Pacific! This is

a few score leagues west of the coast of France

! It is not possible that our oceanographic maps could have missed such a feature! I have sailed above and beneath the waves in these waters for two decades. There is no such trench!’

Lebret lowered himself into a seated position upon the sloping floor, his foot braced against a bulkhead. He lit a new cigarette. The smoke pooled about him like a caul. ‘Quite apart from anything else,’ he observed. ‘Even if we had slipped inside some uncharted fissure, the pressure should have crushed us completely by now.’

‘Six thousand metres,’ announced Le Petomain. ‘Hull pressure … is

decreasing

, sir. How can that be?’

‘It cannot!’ replied the captain. ‘What is the reading?’

‘Four hundred and seven kilograms per square centimetre, sir.’

‘Quite impossible. That pressure gauge

must

be faulty, even if the

depth

gauge is correct. Indeed,’ the captain added, as the idea started up in his head. ‘It is likely that the pressure gauge

would

malfunction. The sensor is not designed to measure pressures of the intensity to which it has been exposed. The very thing it has been measuring would destroy it.’

‘Sir!’

‘Water pressure increases at approximately one hundred kilograms per square centimetre for every thousand metres one descends,’ the captain said, as if speaking to himself. ‘Accordingly we can calculate the approximate pressure that must obtain – if the depth gauge is indeed correct.’

‘The calculation produces a number far in excess of the tolerances of our hull,’ Lebret pointed out.

The captain shook his head again – a gesture of such exaggerated swing he might have been having a conniption fit. ‘No!’ he announced. ‘It

cannot

be. You have kept something from me, Lebret. You and your damn blackface scientists from India, and

your mysterious Jewish-Swiss finance. I don’t care if de Gaulle himself vouched for your patriotism –

you

have kept something

from

me. I don’t know what the

Plongeur’

s hull is made of, but it must be a material tougher than steel. Titanium is it? I have heard rumours that the Americans have built a bathysphere out of titanium, to lower into the Mariana trench. Is that it?’

‘Take a moment, Captain,’ said Lebret, carelessly. ‘And think through what you are saying. You inspected the ship yourself, I presume, before you took her out of port. You went through her inside and out. Yes?’

‘Of course,’ conceded Cloche, reluctantly.

‘You are saying you can’t tell the difference between steel plates and some other metal?’

‘That could hardly be,’ said Cloche. ‘Only I

did

note the newness and thickness of the paint that had been applied to all surfaces.’

‘Quite apart from anything else,’ Lebret said, shaking his head, ‘there

is

no magic material that could preserve a teardrop-shaped cavity of air under the degrees of which we are speaking. Besides – the walls themselves shook and groaned as we descended. And now they are silent. You may believe the evidence of your own senses, I hope?’

The captain pulled on his beard with his right hand, deep in thought. After a moment, Le Petomain sang out: ‘Seven thousand metres, sir! External pressure – according to the read-out, sir – is two hundred kilograms per square centimetre.’

‘Impossible,’ growled Cloche.

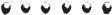

At that moment, Lieutenant Boucher and

Enseigne de vaisseau

Billiard-Fanon climbed back up the corridor and into the bridge. ‘Sir?’ asked the second-in-command. ‘What has happened, sir?’

‘The unexpected quiet is a little oppressive, no?’ laughed Lebret, from his seated position – legs akimbo, bracing himself against the bar in the floor to prevent himself from slipping forward.

‘Both the tanks still refuse to close,’ announced Boucher, pulling himself alongside Le Petomain. ‘But there is good news – if these pressure readings are correct.’

‘How

can

they be?’ snapped Billiard-Fanon, climbing up and checking the instrumentation himself. ‘It’s nonsense!’

‘Sir?’ said the lieutenant. ‘Before, it would not have been possible to pump air back into the tanks, even if we

could

close them. The pressures were much too high – the pump could never have done the work, and the air itself would simply have compressed and liquefied, giving us no buoyancy. But if the pressures are falling at the rate this dial suggests – then soon it

would

be possible to refloat the tanks.’

‘Assuming we can close them.’

‘I know it seems impossible, sir. But if the pressure keeps falling there’s even the chance that we could put a diver into the water. To have a look at the vents from the outside.’

‘At

seven thousand metres

below the surface?’ scoffed Cloche. ‘Don’t talk nonsense. A man in a diving suit would be squashed to jelly in an instant!’

‘But, sir, the pressure gauge reads …’

‘I don’t care what it reads! Would you trust that gauge with

your

life, sailor? I can feel in my bowels that we are still descending – that we’ve been descending without intermission – and accordingly there’s no way that instrument can be wrong! So, we have gone down and down. It follows, as the night the day, by all that is immutable in the laws of physics, that the pressure must be approaching a thousand kilograms per square centimetre.’

The lieutenant did not contradict his captain, but his face betrayed disagreement.

‘Seven thousand five hundred metres,’ announced Le Petomain.

‘It is,’ declared the captain. ‘It is—’ But he could not find in his vocabulary the word that expressed what it was.

‘To have prepared for inevitable catastrophic extinction,’ observed Lebret, lighting yet another cigarette. ‘And then for it simply to evaporate into mystery. It is anticlimactic. Is it not?’ And he laughed.

The captain called a general muster. By the time the entire complement of crew had reassembled in the bridge (with the exception of Pannier, who was discovered dead drunk and passed out in the kitchen), the depth gauge showed a depth of nine thousand metres. The pressure sensors, at the same time, registered a pressure of only eighty kilograms per square centimetre – a lesser weight upon the hull than had obtained before the disaster had struck.

The crew discussed the impossibility of this; but there was nowhere for the discussion to go except round and round. The bottom line was that most of the crew believed the impossibly low pressure reading – it was consistent, after all, with the absence of compression noises from the hull. Some refused to believe it, on the equally reasonable grounds that a depth of nearly a full kilometre must necessarily, by the laws of physics, entail a pressure much greater than the dial showed. This was an unavoidable fact of nature.

A breeze had started up in the cabin; gentle but persistent – it blew at the trouser legs and jacket flaps, and agitated them. Lebret wondered aloud whether it derived from a steeped temperature differential between the outside water and the warmer innards of the craft. It seemed a trivial matter. Men tugged their tunics down, and smoothed their fluttering trouser legs.

Then, Monsieur Ghatwala suggested a means of testing the pressure gauge reading. The

Plongeur

possessed the capacity

to generate its own air by breaking down seawater into its constituent elements of hydrogen and oxygen. To this end small catalyst tanks existed, one on each side of the craft, with systolic hoses connecting them to the open water. ‘Open these,’ Jhutti suggested, ‘and circulate the water. If the external pressures are truly as manageable as the dials suggest, that operation should proceed without a hitch. But if the pressures are what they

should

be at a depth of almost,’ he swallowed before uttering the number, ‘ten thousand metres, then opening the tanks will cause them to crumple.’

‘To crumple,’ said Castor, ‘explosively! That might cause significant damage to the

Plongeur

.’

The captain considered this.

‘Captain,’ put in Jhutti. ‘I might simply note that at a depth of nine and a half thousand metres the

Plongeur

should

long since

have been crushed to a mass of metal. Nobody has dived to such depths! Not in the history of mankind! And I, who know the design parameters of this craft better than any, know that it was not designed for such a thing. Opening the catalytic tanks is a very small risk, when set against the simple impossibility of our being alive at all.’

Cloche nodded a single nod. ‘Do it,’ he ordered.

The tanks were opened. Water circulated, and the atomic pile began its work of recharging the ship’s onboard oxygen supply. Everything happened without a hitch.

‘Extraordinary,’ the captain breathed.

‘It merely confirms the evidence of our own ears,’ was Lebret’s opinion. ‘When the pressure built up, the metal walls of our oceanic coffin shook and wailed. That they have ceased their unpleasant music proves the pressure to have reduced.’

‘But

how

?’ Boucher demanded, banging the side of a bank of instruments with his fist. ‘It is wholly against the laws of physics!’

‘It is,’ confirmed Jhutti. ‘I can see no explanation for it. None at all.’