Ultramarathon Man (26 page)

Authors: DEAN KARNAZES

By the time I wrestled it away from him I was soaking wet. “Where's Gaylord?” I asked Julie.

“He's in the van getting some rest.”

I saw his bare feet sticking out a window and began firing on them.

“Leave me alone and keep running,” he yelped.

“Get out here, Gaylord,” I commanded. “You're coming with me.”

Another blast of water entered my opposite ear. I turned to see Alexandria and Nicholas huddled together, giggling.

“Does anybody need a couple extra crew members?” I addressed the crowd. “They're usually well behaved.”

“Dad!” Alexandria protested, and then she started squirting me in the ear again.

“Get going, Karno,” Gaylord barked out the window.

Man,

I thought departing from the exchange,

what does a guy need to do around here to get some respect?

And I started back out onto the course.

I thought departing from the exchange,

what does a guy need to do around here to get some respect?

And I started back out onto the course.

With 7 miles left to cover, the TV van pulled alongside me again. The reporter fired questions through the open side door. My training, my diet, my motivation.

“It's been an honor to play a small role in helping Libby Wood and her family,” I replied. “That's one thing that's keeping me going.”

“Do you eat dirt?” the reporter asked.

“Do I what?”

“Eat dirt.”

“Excuse me for a moment,” I said, whacking the side of my head. The water in my ear from the kids' attack shook itself out.

“There we go. Now, what was that you asked?”

She gave me her quizzical look again. “Do your feet hurt?”

“Ohh. Yes, my feet hurt pretty bad, but not as bad as my legs. How's that jet pack coming along?”

“You don't look like you need it. Would you mind if we do some creative film work as you run?”

“Can you just focus on my legs down and not show my face? I don't want to be recognized as the lunatic who tried to run himself into extinction.”

They filmed me from every imaginable angle. I figured it would save the coroner a lot of time. Then she asked me one last question.

“So, Team Deanâhow do you do it?”

“Hmm . . .” I pondered. “I ran the first hundred miles with my legs, the next ninety miles with my mind, and I guess I'm running this last part with my heart.”

“That was great!” she said to the cameraman. “We'll see you at the finish line.” And off they sped down the highway.

Dozens of team runners began catching up and passing me on the narrow road to Santa Cruz. Few had any idea I'd been running for the past two days straight as they grunted encouragement while blowing by me. People of all walks of life passed meâyoung and old, experienced runners and new recruits. Periodically some hotshot speed demon, bent on turning in his fastest leg ever, would rocket by me without so much as a nod. A hundred miles ago, I might have been tempted to chase him. But after running the equivalent of seven consecutive marathons nonstop, my ego had been sufficiently tempered, and being passed wasn't the least bit demoralizing.

Until Gaylord passed me.

“Where'd you come from?” I shouted.

“That doesn't much matter, Karno. All that matters is that I'm in front of you!” he crowed.

That was it. I began sprinting after him, and we hobbled down the highway like a pair of geriatric patients trying to reach the bathroom first. It was insanity to be running so hard at this stage of the game. Then again, none of the events over the past two days seemed particularly sane.

“Okay, gentlemen,” my wife chided as she pulled up to us on Gaylord's bike. “Let's come to our senses.”

“He started it,” I whined.

“But he kept it going,” Gaylord whined back.

“Now, children,” Julie interrupted, “keep it together. We're almost done.”

She rode along behind us on Gaylord's bike, keeping close tabs.

“Honey,” I asked sweetly. “Did you happen to bring any food?”

“I found this bag of pretzels sitting on the counter.”

“Hey, those are mine!” Gaylord protested.

“No way!” I slammed back. “Once it enters the Mother Ship, it's community property.”

“Whose rules are those?” he questioned.

“I just made it up right now, but it sounds pretty good.”

“Enough, you two,” Julie weighed in. “Neither of you will get anything if you keep acting like this.”

Gaylord made it about another mile. His fortitude totally impressed me, and I was grateful for every step he had taken by my side. The kid was tough, all right, with a spirit that didn't seem easily broken. He had the makings of an ultra-endurance runner. I hoped he would pursue it, because I now saw the value of having the right training partner. Misery loves company.

He and Julie climbed aboard the Mother Ship and it drove off, leaving me running alone, and largely no longer at the controls. My body was now on autopilot. At moments like these, the slightest physical or mental countercurrent can have seriously debilitating consequences. It becomes critical to believe in your ability to keep going, even if all indications are to the contrary. And all indications began turning to the contrary. I looked down to discover my quadriceps radically engorged and my calves bulging wildly. Sweat streamed down my face. Another meltdown seemed imminent.

The meltdown/euphoria cycle had become so compressed that it was now nearly impossible to distinguish between the two, as if some third mutant state of emotion had polymerized. However I wanted to characterize it, it wasn't good. I was losing control of my body and, worse, my mind. Two days of running was doing weird things to me.

Until I looked up and spotted the blue Pacific on the horizon. The beach was near. Santa Cruz was drawing me in. I thought of the times Pary and I had sat at our kitchen window and looked out at the ocean, and I was suddenly infused with hope. A hundred and ninety-five miles down, five to go.

Somewhere inside I found the fortitude to ignore the physical deterioration and keep placing one foot in front of the other. I willed myself to do so, blocking out all extraneous input and listening only to my heart.

A party was in full progress as I limped up to the final relay exchange station. With just one short leg left, many teams were already celebrating the finish. People danced by the side of the road to loud music. As I drew closer, two of the dancers looked familiar.

Holy shit, was that my mom and dad . . . doing the macarena?

Holy shit, was that my mom and dad . . . doing the macarena?

It was. The sight of my dad hip-swinging and hand-jiving with a loony grin on his sunburned mug was mortifying. Where did he learn to move like that? I felt a great sense of urgency to run on as quickly as possible.

“Aren't you going to stop?” Julie asked from the curbside.

“Are you kidding?” I responded. “Do you see that over there?”

“Yeah,” she smiled. “Your folks have lost it.”

“Aren't there laws against things like that?”

“We're in Santa Cruz. They could be dancing naked and no one would give a hoot.”

“Let's not give them any ideas.”

“Sure you don't want anything?” she chuckled.

I gave her a peck on the cheek. “For those two to stop dancing would be good.”

“Can't help you there,” she said, smiling. “We'll see you at the finish, Team Dean.”

Chapter 17

Run for the Future

You only live once, but if you work it right,

once is enough.

once is enough.

âJoe Louis

Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk Sunday afternoon, October 1, 2000The last 4.7 miles

were considered flat and easyârelative to some of the other legs of the route. But after 195 miles of running, nothing seemed particularly flat and easy to me. Where did this zest to keep going come from?

were considered flat and easyârelative to some of the other legs of the route. But after 195 miles of running, nothing seemed particularly flat and easy to me. Where did this zest to keep going come from?

Running has taught me that the pursuit of a passion matters more than the passion itself. Immerse yourself in something deeply and with heartfelt intensityâcontinually improve, never give upâthis is fulfillment, this is success.

Running into Santa Cruz, I was wholly fulfilled. Most people never get there. They're afraid or unwilling to demand enough of themselves and take the easy road, the path of least resistance. But struggling and suffering, as I now saw it, were the essence of a life worth living. If you're not pushing yourself beyond the comfort zone, if you're not constantly demanding more from yourselfâexpanding and learning as you goâyou're choosing a numb existence. You're denying yourself an extraordinary trip.

As a running buddy once said to me: Life is not a journey to the grave with the intention of arriving safely in a pretty and well-preserved body, but rather to skid in broadside, thoroughly used up, totally worn out, and loudly proclaiming: “WOW!! What a ride!”

Endurance running was my passion, my ride. So here I was, in the driver's seat, running for two days straight, pushing the mental and physical limits, striving to be better, to go farther, to give more. Excelling at my craft meant breaking through psychological barriers and having the guts and resolve to keep trying, even in the face of inexorable pain and menacing hopelessness.

It had been terrifying facing this challenge, there's no denying it. Standing in Calistoga two days ago, I had shuddered with apprehension over an undertaking that could easily obliterate me. Yet I grappled with my fears, stepped over the edge, and engaged in the battle; and forty-six hours later I was still standing. In the world of Team Dean, it's as good as it gets.

Until a delivery truck nearly ran me down.

“Look out, you crazy-ass runner! Watch where you're going!” the driver shouted out the window.

But I was in a crosswalk. I just smiled, however, and waved, incapable of anger. My blood-endorphin level was too high for me to be irritated by something so minor as being run over by a truck.

It was nearing three in the afternoon, and the sun shone brightly overhead as the course wove through the streets of downtown Santa Cruz. A few pedestrians and shoppers waved encouragement, but most had no idea a race was in progress. How funny I must appear, beat to hell and gleaming with sweat, running down the street like Pheidippidesâthe original Greek ultrarunnerâtrying to deliver news to Athens about the victory on the Plain of Marathon. Only we weren't in ancient Greece; we were in the shopping district of Santa Cruz.

With a mile and a half left, the road intersected a popular footpath above the beach. It was crowded with beachgoers, dog-walkers, tourists. I'd moved well beyond runner's high at this point and casually floated along, beaming at the sunlit scene, entirely weightless from the neck down. How it was that a person who'd just run 198 miles could be feeling no pain was inexplicable.

With 1 mile left, my heart started racingâwith joy now, not overexertion. There was no containing my elation, and I began sprinting at top speed.

The footpath continued to parallel the beach on the bluff above. Off in the distance I spotted the famous roller coaster of the Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk, the amusement park that marked the end of the course. Tearing toward the finish, I wove wildly among the surfers with their boards and the errant beachball or two. People let out small hoots and praises as I blasted by, but their faces were just smiling blurs.

The roller coaster drew nearer. I ran toward it. A chute of well-wishers had assembled along the footpath and down to the official finish line on the beach. Other runners studied me quietly, appraising me as I came bounding in, seemingly unsure of how to respond to a man who just spent two days running.

“How 'bout a little cheer?” I goaded the crowd. “I just ran from Calistoga.”

They went berserk.

As I hit the final stretch of beach, my family and Gaylord joined hands with me and we all crossed the finish line together as a team, just the way I had hoped. If my sister could have seen me, I knew that she would be smiling. I couldn't have been any happier.

What had begun as a jog through the Napa Valley forty-six hours and seventeen minutes earlier had ended with a dream coming true. Miraculously, I'd covered the last mile in under six minutesâa pace that I'd find strenuous even on fresh legs. Standing proud at that finish line, I oddly wasn't even winded.

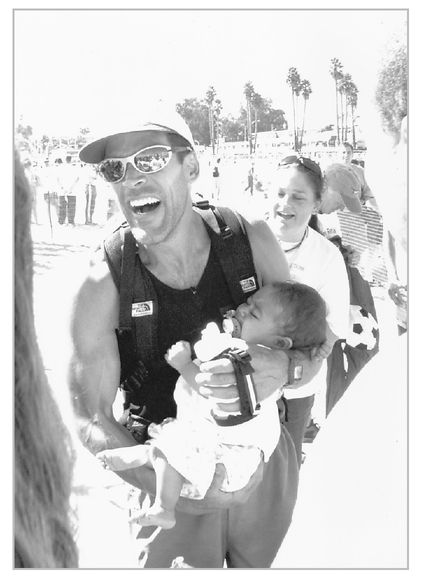

In the ensuing pandemonium, a young child was placed before me. Her dark brown eyes were wide and beaming. I instantly recognized little Libby Wood. Her mother placed her in my arms, and I cradled her fragile body. Although the doctors had said she was nearing death, to me she looked like she was filled with life.

Holding Libby Wood at the finish

“We're so thankful for what you've done,” her mother said.

Other books

Miss Jacobson's Journey by Carola Dunn

They Rode Together by Tell Cotten

Crazy Paving by Louise Doughty

The Saxon Bride (The Norman Conquest Series) by York, Ashley

The Dying Light by Henry Porter

The Treasure at Poldarrow Point (An Angela Marchmont Mystery) by Benson, Clara

Awake by Viola Grace

Absorbed by Crowe, Penelope

Hacked by Tracy Alexander

419 by Will Ferguson