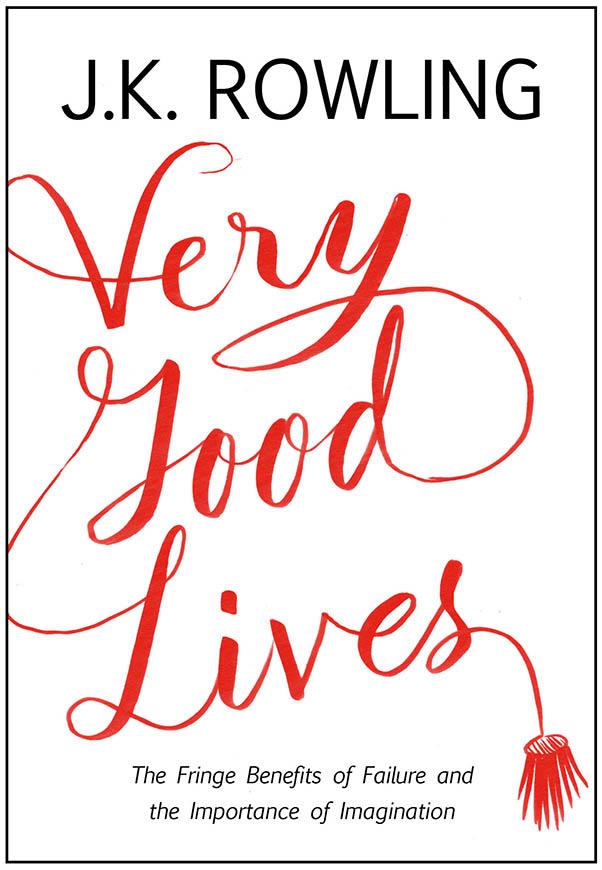

Very Good Lives: The Fringe Benefits of Failure and the Importance of Imagination

Read Very Good Lives: The Fringe Benefits of Failure and the Importance of Imagination Online

Authors: J. K. Rowling

Copyright © 2008 by J.K. Rowling

Cover design by Mario J. Pulice

Cover art by Joel Holland

Cover copyright © 2015 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

littlebrown.com

twitter.com/littlebrown

facebook.com/littlebrownandcompany

First ebook edition: April 2015

Published simultaneously in Great Britain by Little, Brown Book Group.

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Book design by Mario J. Pulice

Illustrations by Joel Holland, © 2015 by Little, Brown and Company

ISBN 978-0-316-36914-5

E3

President Faust, members of the

Harvard Corporation and the

Board of Overseers, members of

the faculty, proud parents, and,

above all, graduates.

The first thing I would like to

say is “thank you.” Not only has

Harvard given me an extraordi-

nary honor, but the weeks of

fear and nausea I have endured

at the thought of giving this com-

mencement address have made

me lose weight. A win-win sit-

uation! Now all I have to do is

take deep breaths, squint at the

red banners, and convince myself

that I am at the world’s largest

Gryffindor reunion.

Delivering a commencement address

is a great responsibility, or so I thought

until I cast my mind back to my

own graduation. The commencement

speaker that day was the distinguished

British philosopher Baroness Mary

Warnock. Reflecting on her speech has

helped me enormously in writing this one,

because it turns out that I can’t remember

a single word she said. This liberating

discovery enables me to proceed without

any fear that I might inadvertently

influence you to abandon promising

careers in business, the law, or politics

for the giddy delights of becoming a

gay wizard.

You see? If all you remember in

years to come is the “gay wizard”

joke, I’ve come out ahead of Baro-

ness Mary Warnock. Achievable

goals: the first step to self-

improvement.

Actually, I have racked my mind

and heart for what I ought to say to

you today. I have asked myself

what I wish I had known at

my own graduation, and what

important lessons I have learned in

the twenty-one years that have

expired between that day and this.

I have come up with two answers.

On this wonderful day when we are

gathered together to celebrate your

academic success, I have decided to talk

to you about the benefits of failure.

And as you stand on the threshold of

what is sometimes called “real life,”

I want to extol the crucial importance

of imagination.

These may seem quixotic or paradox-

ical choices, but please bear with me.

Looking back at the twenty-one-year-

old that I was at graduation is a slightly

uncomfortable experience for the forty-

two-year-old that she has become.

Half my lifetime ago, I was striking

an uneasy balance between the

ambition I had for myself and what

those closest to me expected of me.

I was convinced that the only

thing I wanted to do, ever, was write

novels. However, my parents, both

of whom came from impoverished

backgrounds and neither of whom

had been to college, took the view

that my overactive imagination was

an amusing personal quirk that would

never pay a mortgage or secure a

pension. I know that the irony strikes

with the force of a cartoon anvil

now.

So they hoped that I would take a

vocational degree; I wanted to study

English Literature. A compromise was

reached that in retrospect satisfied

nobody, and I went up to study

Modern Languages. Hardly had my

parents’ car rounded the corner at

the end of the road than I ditched

German and scuttled off down the

Classics corridor.

I cannot remember telling my

parents that I was studying Classics;

they might well have found out

for the first time on graduation day.

Of all the subjects on this planet, I

think they would have been hard

put to name one less useful than

Greek mythology when it came to

securing the keys to an executive

bathroom.

I would like to make it clear,

in parenthesis, that I do not

blame my parents for their

point of view. There is an

expiration date on blaming

your parents for steering you

in the wrong direction; the

moment you are old enough to

take the wheel, responsibility

lies with you. What is more,

I cannot criticize my parents

for hoping that I would never

experience poverty. They had

been poor themselves, and I

have since been poor, and I

quite agree with them that it is

not an ennobling experience.

Poverty entails fear, and stress,

and sometimes depression; it

means a thousand petty humil-

iations and hardships. Climb-

ing out of poverty by your

own efforts—that is something

on which to pride yourself,

but poverty itself is roman-

ticized only by fools.

What I feared most for myself at

your age was not poverty but failure.

At your age, in spite of a distinct

lack of motivation at university,

where I had spent far too long in the

coffee bar writing stories and far too

little time at lectures, I had a knack

for passing examinations, and that,

for years, had been the measure of

success in my life and that of my peers.

I am not dull enough to suppose

that because you are young, gift-

ed, and well-educated, you have

never known hardship or heartache.

Talent and intelligence never yet

inoculated anyone against the ca-

price of the Fates, and I do not for

a moment suppose that everyone

here has enjoyed an existence of un-

ruffled privilege and contentment.

you

However, the fact that you are

graduating from Harvard suggests

that you are not very well acquainted

with failure. You might be driven

by a fear of failure quite as much as

a desire for success. Indeed, your

conception of failure might not be

too far removed from the average

person’s idea of success, so high

have you already flown.

biggest

failure

I knew

Ultimately we all have to decide for

ourselves what constitutes failure, but

the world is quite eager to give you a

set of criteria, if you let it. So I think

it fair to say that by any conventional

measure, a mere seven years after my

graduation day, I had failed on an epic

scale. An exceptionally short-lived

marriage had imploded, and I was job-

less, a lone parent, and as poor as it is

possible to be in modern Britain

without being homeless. The fears that

my parents had had for me, and that I

had had for myself, had both come to

pass, and by every usual standard I was

the biggest failure I knew.

Now, I am not going to stand here

and tell you that failure is fun. That

period of my life was a dark one, and

I had no idea that there was going to

be what the press has since represented

as a kind of fairy-tale resolution. I

had no idea then how far the tunnel

extended, and for a long time any

light at the end of it was a hope rather

than a reality.

So why do I talk about the benefits of

failure? Simply because failure meant

a stripping away of the inessential. I

stopped pretending to myself that I was

anything other than what I was and

began to direct all my energy into

finishing the only work that mattered

to me. Had I really succeeded at any-

thing else, I might never have found

the determination to succeed in the

one arena where I believed I truly

belonged. I was set free, because my

greatest fear had been realized, and I

was still alive, and I still had a daughter

whom I adored, and I had an old

typewriter and a big idea. And so

rock bottom became the solid foun-

dation on which I rebuilt my life.

You might never fail on the scale

I did, but some failure in life is

inevitable. It is impossible to live

without failing at something, unless

you live so cautiously that you might

as well not have lived at all—in

which case, you fail by default.

Failure gave me an inner security

that I had never attained by passing

examinations. Failure taught me

things about myself that I could have

learned no other way. I discovered

that I had a strong will and more

discipline than I had suspected; I also

found out that I had friends whose

value was truly above the price of rubies.

The knowledge that you have

emerged wiser and stronger from

setbacks means that you are, ever

after, secure in your ability to

survive. You will never truly

know yourself, or the strength of

your relationships, until both have

been tested by adversity. Such

knowledge is a true gift, for all

that it is painfully won, and it has

been worth more than any qualifi-

cation I’ve ever earned.

So given a Time-Turner, I would

tell my twenty-one-year-old self

that personal happiness lies in

knowing that life is not a checklist

of acquisition or achievement. Your

qualifications, your CV, are not your

life, though you will meet many

people of my age and older who

confuse the two. Life is difficult,

and complicated, and beyond any-

one’s total control, and the humil-

ity to know that will enable you

to survive its vicissitudes.

Now you might think that I chose

my second theme, the importance of

imagination, because of the part it

played in rebuilding my life, but that

is not wholly so. Though I personally

will defend the value of bedtime

stories to my last gasp, I have learned

to value imagination in a much

broader sense. Imagination is not

only the uniquely human capacity

to envision that which is not, and

therefore the fount of all invention

and innovation; in its arguably most

transformative and revelatory capa-

city, it is the power that enables us

to empathize with humans whose

experiences we have never shared.

One of the greatest formative

experiences of my life preceded

Harry Potter, though it informed

much of what I subsequently wrote

in those books. This revelation came

in the form of one of my earliest

day jobs. Though I was sloping off

to write stories during my lunch

hours, I paid the rent in my early

twenties by working at the African

research department of Amnesty

International’s headquarters in Lon-

don.