War of the Whales (61 page)

Authors: Joshua Horwitz

For an engaging one-volume history of submersibles, read

The Navy Times Book of Submarines: A Political, Social, and Military History

by Brayton Harris, edited by Walter J. Boyne (Berkley Books, 1997).

The Navy Times Book of Submarines: A Political, Social, and Military History

by Brayton Harris, edited by Walter J. Boyne (Berkley Books, 1997).

My favorite nonfiction book ever written about the “silent service” of Cold War submariners is

Blind Man’s Bluff: The Untold Story of American Submarine Espionage

by Sherry Sontag and Christopher Drew with Annette Lawrence Drew (Harper Perennial, 2000).

Blind Man’s Bluff: The Untold Story of American Submarine Espionage

by Sherry Sontag and Christopher Drew with Annette Lawrence Drew (Harper Perennial, 2000).

Ann Finkbeiner’s

The Jasons: The Secret History of Science’s Postwar Elite

(Viking, 2006) is the only book ever written about this shadowy military think tank, and a very good read.

The Jasons: The Secret History of Science’s Postwar Elite

(Viking, 2006) is the only book ever written about this shadowy military think tank, and a very good read.

Dick Russell’s

Eye of the Whale: Epic Passage from Baja to Siberia

(Simon & Schuster, 2001) narrates the natural history and remarkable annual migration of the California gray whale.

Eye of the Whale: Epic Passage from Baja to Siberia

(Simon & Schuster, 2001) narrates the natural history and remarkable annual migration of the California gray whale.

Here’s where the long, strange trip into interspecies communication all began: John Lilly’s

Man and Dolphin: Adventures on a New Scientific Frontier

(Doubleday, 1961).

Man and Dolphin: Adventures on a New Scientific Frontier

(Doubleday, 1961).

Take a trip back to the 1970s at the apex of metaphysical speculation on cetacean consciousness with

Mind in the Waters: A Book to Celebrate the Consciousness of Whales and Dolphins

(Scribner, 1974), edited by Joan McIntyre, with essays, poems, and discourses by the pantheon of Save the Whales apostles, from John Lilly to Paul Spong to Farley Mowat.

Mind in the Waters: A Book to Celebrate the Consciousness of Whales and Dolphins

(Scribner, 1974), edited by Joan McIntyre, with essays, poems, and discourses by the pantheon of Save the Whales apostles, from John Lilly to Paul Spong to Farley Mowat.

The “official story,” but still the most detailed account of the US Navy’s Marine Mammal Program, by its first director, Forrest G. Wood:

Marine Mammals and Man: The Navy’s Porpoises and Sea Lions

(R. B. Luce, 1973).

Marine Mammals and Man: The Navy’s Porpoises and Sea Lions

(R. B. Luce, 1973).

For great reporting on worldwide ocean ecology and culture, read David Helvarg’s

Blue Frontier: Dispatches from America’s Ocean Wilderness

(Sierra Club Books, 2006).

Blue Frontier: Dispatches from America’s Ocean Wilderness

(Sierra Club Books, 2006).

The most authoritative and beautifully photographed book about orcas is

Killer Whales: The Natural History and Genealogy of Orcinus Orca in British Columbia and Washington State

by John K. B. Ford, Graeme M. Ellis, and Kenneth C. Balcomb (University of Washington Press, 2000).

Killer Whales: The Natural History and Genealogy of Orcinus Orca in British Columbia and Washington State

by John K. B. Ford, Graeme M. Ellis, and Kenneth C. Balcomb (University of Washington Press, 2000).

Roger Payne’s memoir of his forays into whale research and activism,

Among Whales

(Scribner, 1995) remains a fascinating read 20 years later.

Among Whales

(Scribner, 1995) remains a fascinating read 20 years later.

For an informed and provocative investigation into whale songs and music across species, tune in to

Thousand Mile Song: Whale Music in a Sea of Sound

by David Rothenberg (Basic Books, 2008).

Thousand Mile Song: Whale Music in a Sea of Sound

by David Rothenberg (Basic Books, 2008).

Two recently published cultural histories of whales, by authors with voice and humor, are Joe Roman’s

Whale

(Reaktion Books, 2006) and

The Whale: In Search of the Giants of the Sea

by Philip Hoare (HarperCollins, 2010).

Whale

(Reaktion Books, 2006) and

The Whale: In Search of the Giants of the Sea

by Philip Hoare (HarperCollins, 2010).

ONLINE RESOURCES

You can find range of links to online resources on my book website: warofthewhales.com, including the ones below.

Whale evolution is artfully illustrated in two short animated videos: from the Smithsonian Institution, ocean.si.edu/ocean-videos/evolution-whales-animation; and from the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, collections.tepapa.govt.nz/exhibitions/whales/Segment.aspx?irn=161.

Ocean noise pollution and its threat to whales is concisely portrayed in the four-minute animation by Silent Oceans, http://vimeo.com/67804123.

Two excellent websites devoted to ocean acoustics are the Acoustic Ecology Institute, acousticecology.org; and Discovery of Sound in the Sea, dosits.org.

A very cool online gallery of CT images of marine mammal ears and other anatomy is viewable at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s CSI Computerized Scanning and Imaging site: http://csi.whoi.edu.

MARINE CONSERVATION AND RESEARCH ORGANIZATIONS WORKING TO REDUCE OCEAN NOISE

Center for Whale Research, whaleresearch.com

Natural Resources Defense Council, nrdc.org

International Fund for Animal Welfare, ifaw.org

Earthjustice, earthjustice.org

Bahamas Marine Mammal Research Organisation, bahamaswhales.org

Whale and Dolphin Conservation, us.whales.org

World Wildlife Fund, worldwildlife.org

Oceana, oceana.org

Animal Legal Defense Fund, aldf.org

We hope you enjoyed reading this Simon & Schuster eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Simon & Schuster.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

ENDNOTES

Chapter 1: The Day the Whales Came Ashore

1. Marta Azzolini, an Italian intern working with the Bahamas Marine Mammal Survey in the spring of 2000 and one of the strongest swimmers of the group, assisted Diane Claridge by swimming alongside the Cuvier’s whale and guiding him out to deeper water.

Chapter 2: Castaways

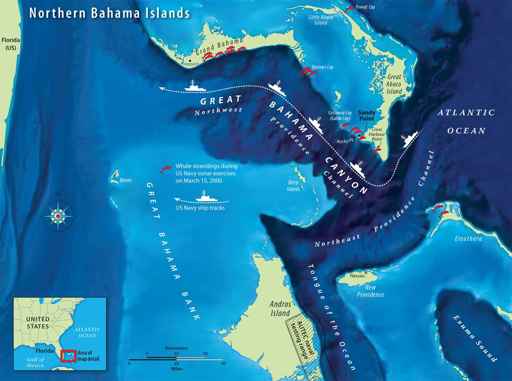

1. The Atlantic Undersea Test and Evaluation Center (AUTEC) is the US Navy’s premier submarine torpedo and sonar test range. Constructed in the 1960s, AUTEC lies 117 miles east of Florida and 60 miles southwest of Abaco. AUTEC’s Tongue of the Ocean waterway, at the edge of the Great Bahama Bank, is a unique, flat-bottom deep-water basin approximately 110 nautical miles long and 20 nautical miles wide, and a mile deep. Its flat basin floor enabled the Navy to install extensive arrays of bottom-mounted hydrophones to make precise measurements of acoustic activity inside and surrounding the range.

Chapter 3: Taking Heads

1. Research by Chris Clark at Cornell University on blue whales—which are baleen rather than toothed whales—indicates that they emit very loud sounds at very low frequencies (180 decibels, 14 hertz), which may constitute long-distance echolocation. The idea is that they might bounce their signals off islands, seamounts, or other oceanic features, and, by listening to the returning echo, recognize the “landmark” to locate their position.

2. The co-evolution of deep-diving beaked whales and squid is described in a journal article by two evolutionary biologists at the University of California at Berkeley: David R. Lindberg and Nicholas D. Pyenson, “Things That Go Bump in the Night: Evolutionary Interactions Between Cephalopods and Cetaceans in the Tertiary,”

Lethaia

40, no. 4 (December 2007): 335–43.

Lethaia

40, no. 4 (December 2007): 335–43.

3. Until recently, sperm whales and southern elephant seals had competed with Cuvier’s beaked whales for record for the deepest and longest dives by an air-breathing animal. But in March of 2014, researchers tracking Cuvier’s off the California using electronic tags recorded a record-smashing dive of almost 10,000 feet in depth—the equivalent of eight Empire State Buildings stacked one on top of another. A different Cuvier’s dive was timed at more than two hours, breaking the record of 120 minutes by an elephant seal. Schorr GS, Falcone EA, Moretti DJ, Andrews RD (2014) “First Long-Term Behavioral Records from Cuvier’s Beaked Whales (

Ziphius cavirostris

) Reveal Record-Breaking Dives.” PLoS ONE 9(3): e92633. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0092633.

Ziphius cavirostris

) Reveal Record-Breaking Dives.” PLoS ONE 9(3): e92633. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0092633.

4. “The bends”: Under pressure, nitrogen in the lung air’s oxygen-nitrogen mix is absorbed at greater than normal concentrations into the diver’s blood and tissue. The longer a diver remains at depth, the more gradually he needs to ascend to normal atmospheric pressure to allow the nitrogen to reabsorb into the lungs. If he surfaces too quickly, the nitrogen expands and forms bubbles—in much the way that a can of soda forms bubbles when you open it, quickly reducing the pressure inside. The nitrogen bubbles that form in tissue during rapid ascent cause extreme pain in the joints. If a bubble in the blood travels to the brain, it can paralyze or even kill you.

5. The deepest-diving military submarines—the Soviet Alfa-class submarines, constructed at extraordinary expense out of titanium alloy during the height of the Cold War—reached crush depth at 3,700 feet meters. Cuvier’s beaked whales have been measured to dive to almost 1,000 feet.

6. There were multiple aerial sightings of warships in Bahamian waters from March 16–18, including by neighbors of Balcomb’s in Northwest Providence Channel near Grand Bahama on March 16 and by Balcomb in Tongue of the Ocean on March 18th. For a precise linear narrative of the stranding and its aftermath, see Balcomb and Claridge’s peer-reviewed and published report: K. C. Balcomb and D. E. Claridge, “A Mass Stranding of Cetaceans Caused by Naval Sonar in the Bahamas,”

Bahamas Journal of Science

8, no. 2 (May 2001): 4–6.

Bahamas Journal of Science

8, no. 2 (May 2001): 4–6.

Chapter 4: The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Beachcomber

1. John Dominis’ photographs of humpback whales appeared in the August 2, 1963, issue of

Life

magazine, pp. 38–45.

Life

magazine, pp. 38–45.

2. Balcomb, and the newspaper-reading public, later found out that the Smithsonian and Army bird-banding project was a $3 million classified program funded by the Army’s Chemical and Biological Warfare Division in Fort Detrick, Maryland. The Army wanted to study the birds’ migratory patterns and range to determine if (1) migratory birds might inadvertently spread biological and germ warfare agents from test sites in the Pacific to populations on the mainland, and (2) these same birds might be deployed as an “avian vector of disease” to intentionally deliver biological weapons to targets across borders. When first confronted with rumors of such a collaboration with the Army in 1969, the leadership of the Smithsonian vehemently denied any involvement. But when documentary evidence came to light in 1985, the Smithsonian vowed to never again accept contracts for classified military research. See also P. M. Boffey, “Biological Warfare: Is the Smithsonian Really a ‘Cover’?”

Science

163, no. 3869 (February 21, 1969): 791–96; Ted Gup, “Pacific Gulls Doubled as War Hawks,”

Washington Post

, May 20, 1985, A1.

Science

163, no. 3869 (February 21, 1969): 791–96; Ted Gup, “Pacific Gulls Doubled as War Hawks,”

Washington Post

, May 20, 1985, A1.

Chapter 5: In the Silent Service

1. Radar, developed in the 1930s at the US Naval Research Lab to target and track surface ships and aircraft, uses echolocation by bouncing radio waves, rather than sound waves, off of objects. In addition to finding submarines once they had surfaced, radar could also detect a snorkel or periscope that penetrated the surface to breathe air or scan for ships. It wasn’t until WWII that the term “sonar” was coined (for sound navigation ranging) to parallel the naming of radar (radio detecting and ranging).

2. According to Norman Polmar, “The Soviet Navy: How Many Submarines?”

Proceedings

124, no. 2 (February 1998): 1, www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1998-02/soviet-navy-how-many-submarines, from 1945 through 1991, the Soviet Union produced 727 submarines—492 with diesel-electric or closed-cycle propulsion and 235 with nuclear propulsion. This compares with the US total of 212 submarines—43 with diesel propulsion (22 from World War II programs) and 169 nuclear submarines (including the diminutive NR-1). Not included are Soviet midget submarines and the single US midget, the X-1 (USS

X-1

).

Proceedings

124, no. 2 (February 1998): 1, www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1998-02/soviet-navy-how-many-submarines, from 1945 through 1991, the Soviet Union produced 727 submarines—492 with diesel-electric or closed-cycle propulsion and 235 with nuclear propulsion. This compares with the US total of 212 submarines—43 with diesel propulsion (22 from World War II programs) and 169 nuclear submarines (including the diminutive NR-1). Not included are Soviet midget submarines and the single US midget, the X-1 (USS

X-1

).

3. In one of the odd coincidences of scientific exploration, a Russian acoustician named Leonid Brekhovskikh made a virtually simultaneous and independent discovery of the deep sound channel during wartime explosive experiments in the Sea of Japan. But because of the secrecy of Soviet and American acoustic research, these WWII allies and Cold War adversaries wouldn’t learn of each other’s discoveries for many decades.

4. Ewing’s pilot rescue system was ingenious. The downed pilot would drop a hollow metal sphere from his floating dinghy into the ocean. It would sink and eventually implode at the increased water pressure at 3,000 feet, sending a low-frequency sound signal through the deep sound channel to two or more bottom-mounted receivers connected by cable to coastal listening stations thousands of miles away. Once the pilot’s position was triangulated, rescue aircraft could be dispatched from the nearest carrier in the Pacific.

5. For most of the Cold War, SOSUS represented the only way a woman could claim warfare experience and compete with her male counterparts on a nearly equal basis. Before the early 1980s, when women began being assigned to surface ships and were accepted into flight training, SOSUS was an opportunity for women who wanted to serve in an operational role in the US Navy. Female line officers started being assigned to the SOSUS stations in 1970 when Norah Anderson joined the listening station on Eleuthera and became the first woman to take a place on the operations floor.

See also Gary Weir, “The American Sound Surveillance System: Using the Ocean to Hunt Soviet Submarines, 1950–1961,”

International Journal of Naval History

5, no. 2 (August 2006): 12–18. According to naval historian Weir, “Since the Navy classified SOSUS activity as a warfare specialty, the door opened for hundreds of women to a Navy career outside of medicine, education, or administration.”

International Journal of Naval History

5, no. 2 (August 2006): 12–18. According to naval historian Weir, “Since the Navy classified SOSUS activity as a warfare specialty, the door opened for hundreds of women to a Navy career outside of medicine, education, or administration.”

Other books

The Invisible Mountain by Carolina de Robertis

Crazy by William Peter Blatty

The Tollkeeper (Fairy Tales Behaving Badly) by Eppa, Annie

The Redheaded Princess: A Novel by Ann Rinaldi

Notes From a Small Island by Bryson, Bill

Two Girls Fat and Thin by Mary Gaitskill

Tension by R. L. Griffin

A Box of Gargoyles by Anne Nesbet

Daughters of the Dagger 04 - Amethyst by Elizabeth Rose

Demon Moon by Meljean Brook