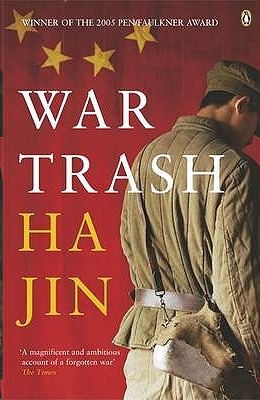

War Trash

War Trash

Ha Jin

From Publishers Weekly

Jin (Waiting; The Crazed; etc.) applies his steady gaze and stripped-bare storytelling to the violence and horrifying political uncertainty of the Korean War in this brave, complex and politically timely work, the story of a reluctant soldier trying to survive a POW camp and reunite with his family. Armed with reams of research, the National Book Award winner aims to give readers a tale that is as much historical record as examination of personal struggle. After his division is decimated by superior American forces, Chinese "volunteer" Yu Yuan, an English-speaking clerical officer with a largely pragmatic loyalty to the Communists, rejects revolutionary martyrdom and submits to capture. In the POW camp, his ability to communicate with the Americans thrusts him to the center of a disturbingly bloody power struggle between two factions of Chinese prisoners: the pro-Nationalists, led in part by the sadistic Liu Tai-an, who publicly guts and dissects one of his enemies; and the pro-Communists, commanded by the coldly manipulative Pei Shan, who wants to use Yu to save his own political skin. An unofficial fighter in a foreign war, shameful in the eyes of his own government for his failure to die, Yu can only stand and watch as his dreams of seeing his mother and fiancée again are eviscerated in what increasingly looks like a meaningless conflict. The parallels with America 's current war on terrorism are obvious, but Jin, himself an ex-soldier, is not trying to make a political statement. His gaze is unfiltered, camera-like, and the images he records are all the more powerful for their simple honesty. It is one of the enduring frustrations of Jin's work that powerful passages of description are interspersed with somewhat wooden dialogue, but the force of this story, painted with starkly melancholy longing, pulls the reader inexorably along.

From The New Yorker

Ha Jin's new novel is the fictional memoir of a Chinese People's Volunteer, dispatched by his government to fight for the Communist cause in the Korean War. Yu Yuan describes his ordeal after capture, when P.O.W.s in the prison camp have to make a wrenching choice: return to the mainland as disgraced captives, or leave their families and begin new lives in Taiwan. The subject is fascinating, but in execution the novel often seems burdened by voluminous research, and it strains dutifully to illustrate political truisms. In a prologue, Yuan claims to be telling his story in English because it is "the only gift a poor man like me can bequeath his American grandchildren." Ha Jin accurately reproduces the voice of a non-native speaker, but the labored prose is disappointing from an author whose previous work – "Waiting" and " Ocean of Words " – is notable for its vividness and its emotional precision.

Ha Jin

War Trash

PROLOGUE

Below my navel stretches a long tattoo that says "FUCK… U… S…" The skin above those dots has shriveled as though scarred by burns. Like a talisman, the tattoo has protected me in China for almost five decades. Before coming to the States, I wondered whether I should have it removed. I decided not to, not because I cherished it or was nervous about the surgery, but because if I had done that, word would have spread and the authorities, suspecting I wouldn't return, might have revoked my passport. In addition, I was planning to bring with me all the material I had collected for this memoir, and couldn't afford to attract the attention of the police, who might have confiscated my notes and files. Now I am here, and my tattoo has lost its charm; instead, it has become a constant concern. When I was clearing customs in Atlanta two weeks ago, my heart fluttered like a trapped pigeon, afraid that the husky, cheerful-voiced officer might suspect something – that he might lead me into a room and order me to undress. The tattoo could have caused me to be refused entry to the States.

Sometimes when I walk along the streets here, a sudden consternation will overtake me, as though an invisible hand might grip the front of my shirt and pull it out of my belt to reveal my secret to passersby.

However sultry a summer day it is, I won't unbutton my shirt all the way down. When I run a hot bath in the evenings, which I'm very fond of doing and which I think is the best of American amenities, I carefully lock the bathroom, for fear that Karie, my Cambodian-born daughter-in-law, might by chance catch a glimpse of the words on my belly. She knows I fought in Korea and want to write a memoir of that war while I am here. Yet at this stage I don't want to reveal any of its contents to others or I might lose my wind when I take up the pen.

Last Friday as I was napping, Candie, my three-year-old granddaughter, poked at my exposed belly and traced the contour of the words with her finger. She understood the meaning of "U… S…" but not the verb before it. Feeling itchy, I woke up, only to find her tadpole-shaped eyes flickering. She grinned, then pursed her lips, her apple face tightening. Before I could say a word, she spun around and cried, "Mommy, Grandpa has a tattoo on his tummy!"

I jumped out of bed and caught her before she could reach the door. Luckily her mother was not in. "Shh, Candie," I said, putting my finger to my lips. "Don't tell anybody. It's our secret."

"Okay." She smiled as if she had suspected this all along.

That afternoon I took her to Asian Square on Buford Highway and bought her a chunk of hawthorn jelly and a box of taro crackers, for which she gleefully smacked me twice on the cheek. She promised not to breathe a word about my tattoo, not even to her brother, Bobby. But I doubt if she can keep her promise for long. Certainly she will remember seeing it and will rack her little brain trying to unravel the mystery.

My grandson Bobby, a bright boy, is almost seven years old, and I often ask him what he will do when he grows up. Shaking his chubby face, he answers, "Don't know."

"How about being a doctor?" I suggest.

"No, I want to be a scientist or an astronomer."

"An astronomer must spend a lot of time at an observatory, so it's hard for him to keep a family."

His mother's fruity voice breaks in: "Dad, don't press him again."

"I'm not trying to make him do anything. It's just a suggestion."

"He should follow his own interests," my son calls out.

So I shut up. They probably think I'm greedy, eager to see my grandson wallow in wealth. But my wish has nothing to do with money.

From the depths of my heart I believe medicine is a noble, humane profession. If I were born again, I would study medical science devotedly. This thought has been rooted in my mind for five decades. I cannot explain in detail to my son and daughter-in-law why I often urge Bobby to think of becoming a doctor, because the story would involve too much horror and pain. In brief, this desire of mine has been bred by my memories of the wasted lives I saw in Korea and China. Doctors and nurses follow a different set of ethics, which enables them to transcend political nonsense and man-made enmity and to act with compassion and human decency.

In eight or nine months I will go back to China, the land that has raised and nourished me and will retain my bones. Already seventy-three years old, with my wife and daughter and another grandson back home, I won't be coming to the States again. Before I go, I must complete this memoir I have planned to write for more than half of my life. I'm going to do it in English, a language I started learning at the age of fourteen, and I'm going to tell my story in a documentary manner so as to preserve historical accuracy. I hope that someday Candie and Bobby and their parents will read these pages so that they can feel the full weight of the tattoo on my belly. I regard this memoir as the only gift a poor man like me can bequeath his American grandchildren.

1. CROSSING THE YALU

Before the Communists came to power in 1949, I was a sophomore at the Huangpu Military Academy, majoring in political education. The school, at that time based in Chengdu, the capital of Szechuan Province, had played a vital part in the Nationalist regime. Chiang Kai-shek had once been its principal, and many of his generals had graduated from it. In some ways, the role of the Huangpu in the Nationalist army was like that of West Point in the American military. The cadets at the Huangpu had been disgusted with the corruption of the Nationalists, so they readily surrendered to the People's Liberation Army when the Communists arrived. The new government disbanded our academy and turned it into a part of the Southwestern University of Military and Political Sciences. We were encouraged to continue our studies and prepare ourselves to serve the new China. The Communists promised to treat us fairly, without any discrimination. Unlike most of my fellow students who specialized in military science, however, I dared not raise my hopes very high, because the political courses I had taken in the old academy were of no use to the People's Liberation Army. I was more likely to be viewed as a backward case, if not a reactionary. At the university, established mainly for reindoctrinating the former Nationalist officers and cadets, we were taught the basic ideas of Marx, Lenin, Stalin, and Mao Zedong, and we had to write out our personal histories, confess our wrongdoings, and engage in self- and mutual criticism. A few stubborn officers from the old army wouldn't relinquish their former outlook and were punished in the reeducation program – they were imprisoned in a small house at the northeastern corner of our campus. But since I had never resisted the Communists, I felt relatively safe. I didn't learn much in the new school except for some principles of the proletarian revolution.

At graduation the next fall, I was assigned to the 180th Division of the People's Liberation Army, a unit noted for its battle achievements in the war against the Japanese invaders and in the civil war. I was happy because I started as a junior officer at its headquarters garrisoned in Chengdu City, where my mother was living. My father had passed away three years before, and my assignment would enable me to take care of my mother. Besides, I had just become engaged to a girl, a student of fine arts at Szechuan Teachers College, majoring in choreography. Her name was Tao Julan, and she lived in the same city. We planned to get married the next year, preferably in the fall after she graduated. In every direction I turned, life seemed to smile upon me. It was as if all the shadows were lifting. The Communists had brought order to our country and hope to the common people. I had never been so cheerful.

Three times a week I had to attend political study sessions. We read and discussed documents issued by the Central Committee and writings by Stalin and Chairman Mao, such as The History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, On the People's Democratic Dictatorship, and On the Protracted War. Because about half of our division was composed of men from the Nationalist army, including hundreds of officers, the study sessions felt like a formality and didn't bother me much. The commissar of the Eighteenth Army Group, Hu Yaobang, who thirty years later became the Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, even declared at a meeting that our division would never leave Szechuan and that from now on we must devote ourselves to rebuilding our country. I felt grateful to the Communists, who seemed finally to have brought peace to our war-battered land.

Then the situation changed. Three weeks before the Spring Festival of 1951, we received orders to move to Hebei, a barren province adjacent to Manchuria, where we would prepare to enter Korea. This came as a surprise, because we were a poorly equipped division and the Korean War had been so far away that we hadn't expected to participate. I wanted to have a photograph taken with my fiancée before I departed, but I couldn't find the time, so we just exchanged snapshots. She promised to care for my mother while I was gone. My mother wept, telling me to obey orders and fight bravely, and saying, "I won't close my eyes without seeing you back, my son." I promised her that I would return, although in the back of my mind lingered the fear that I might fall on a battlefield.

Julan wasn't a pretty girl, but she was even-tempered and had a fine figure, a born dancer with long, supple limbs. She wore a pair of thick braids, and her clear eyes were innocently vivid. When she smiled, her straight teeth would flash. It was her radiant smile that had caught my heart. She was terribly upset by my imminent departure, but accepted our separation as a necessary sacrifice for our motherland. To most Chinese, it was obvious that MacArthur's army intended to cross the Yalu River and seize Manchuria, the Northeast of China. As a serviceman I was obligated to go to the front and defend our country. Julan understood this, and in public she even took pride in me, though in private she often shed tears. I tried to comfort her, saying, "Don't worry. I'll be back in a year or two." We promised to wait for each other. She broke her jade barrette and gave me a half as a pledge of her love.

After a four-day train ride, our division arrived at a villagelike town named Potou, in Cang County, Hebei Province. There we shed our assorted old weapons and were armed with burp guns and artillery pieces made in Russia. From now on all our equipment had to be standardized. Without delay we began to learn how to use the new weapons. The instructions were only in Russian, but nobody in our division understood the Cyrillic alphabet. Some units complained that they couldn't figure out how to operate the antiaircraft machine guns effectively. Who could help them? They asked around but didn't find any guidance. As a last resort, the commissar of our division, Pei Shan, consulted a Russian military attache who could speak Chinese and who happened to share a table with Pei at a state dinner held in Tianjin City, but the Russian officer couldn't help us either. So the soldiers were ordered: "Learn to master your weapons through using them."