War: What is it good for? (62 page)

Read War: What is it good for? Online

Authors: Ian Morris

One of the reasons that American military dominance is so overwhelming in the mid-2010s is that the United States not only has a bigger economy than China (roughly $15 trillion versus $12 trillion in 2012, calculated at purchasing power parity) but also spends more of it (4.8 percent versus 2.1 percent) on preparing for war. But that too is changing. Chinese military investment, after more than doubling between 1991 and 2001 and then tripling again in the next decade, will probably slow in the 2010s; but American spending will actually shrink. After failing to find a plan to deal with its $16.7 trillion debt mountainâ$148,000 per taxpayerâthe American government imposed across-the-board cuts on itself in March 2013. Military spending, which stood at $690 billion in 2012, was capped at $475 billion; by 2023, it will be lower in real terms than it was in 2010.

It will take China decades to catch up with the American military budget (in 2012, the gap was $228 billion at purchasing power parity), and even then it will probably not have wiped out the lead in morale, command and control, and all-around effectiveness that American forces have built up across a century of preeminence. But that, perhaps, is not the most important point. Britain ceased to be an effective globocop long before any

individual foreign power could have beaten its navy in a straight fight, and much the same fate awaits the United States as soon as it can no longer afford armed forces powerful enough to intimidate everyone at once. The 2010s, warns Michael O'Hanlon of the Brookings Institution, will probably force “dramatic changes in America's basic strategic approach to the world ⦠[and] while hardly emasculating the country or its armed forces, [the cuts] would be too risky for the world in which we live.”

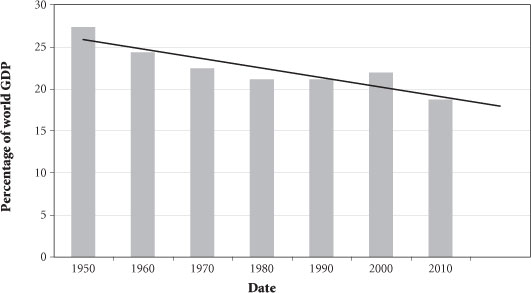

“The most significant threat to our national security,” the outgoing chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff warned in 2010, “is our debt.” But this in fact understates the problem in two big ways: first, debt is just a symptom of the deeper issue of American relative economic decline (

Figure 7.7

); and second, the United States' economic problems threaten the entire world's security, not just its own.

Figure 7.7. Slippery slope: the economic decline of the United States relative to the rest of the worldâgradual in the 1950sâ70s, partially reversed in the 1980sâ90s, and precipitous since 2000

If the downward trend of the last sixty years continues for another forty, the United States will lose the economic dominance it needs to be a globocop. Like Britain around 1900, it may have to farm out parts of its beat to allies, multiplying unknown unknowns. To the rising powers of the 2010s and probably the 2020s too, any move that risks war with the United States smacks of madness. But the payoffs may look very different to the rising powers of the 2030s and 2040s. Absent an American economic revival, the

2050s may have much in common with the 1910s, with no one quite sure whether the globocop can still outgun everyone else.

The Years of Living Dangerously

“We are headed into uncharted waters,” warns the National Intelligence Council in

Global Trends 2030,

the 2012 edition of the strategic foresight report that it presents every four years to the newly elected or reelected American president.

7

The real issue in the 2010s, they suggest, is not just that the United States has failed to prevent the emergence of a new rival; it is that the great-power politicking that worried the drafters of the Defense Planning Guidance twenty years ago is in fact just the tip of a much bigger iceberg of uncertainty.

Deep below the surface, says the council, are seven “tectonic shifts,” playing out slowly across the coming decades: the growth of the global middle class, wider access to lethal and disruptive technologies, the shift of economic power toward the East and the South, unprecedented and widespread aging, urbanization, food and water pressures, and the return of American energy independence. Not all of these will work against the globocop's interests, but at the very least all seem likely to complicate its job. Nearer the surface, the council sees six “game-changers ⦠questions regarding the global economy, governance, conflict, regional instability, technology, and the role of the United States.” Any of these could blow up at any point, rearranging the geopolitical landscape in a matter of weeks. And right on the waterline, says the council, operating on even shorter timescales, comes a bevy of “black swans”âeverything from pandemics, through solar storms that cripple the world's electricity supply, to the collapse of the euro.

The unstable years between 1870 and 1914 had uncertainties of their own, but, the council points out, we have now added an entirely new challenge: climate change. Of the hundred billion tons of carbon dioxide that humans have pumped into the air since 1750, a full quarter was belched out between 2000 and 2010. On May 10, 2013, the carbon dioxide in the

atmosphere briefly peaked above four hundred parts per million, its highest level in 800,000 years. Average temperatures rose 1.5°F between 1910 and 2010, and the ten hottest years on record have all been since 1998.

So far, the effects have been fairly small, but the worst impacts have come in what the council calls an “arc of instability” (

Figure 7.8

). The news from this crescent of poor, arid, politically unstable, but often energy-rich lands is mostly bad. Water flow in the mighty Euphrates River, which irrigates much of Syria and Iraq, has declined by one-third in recent decades, and the water table in its drainage basin dropped by a foot each year between 2006 and 2009. In 2013, Egypt even hinted at war if Ethiopia went ahead with a giant dam on the Nile. Extreme weather will roil the arc with more droughts, more crop failures, and millions more migrants. It is a recipe for more Boer Wars.

Figure 7.8. Feeling the heat: the darker the shading on a region, the more vulnerable it is to drought. Rich countries, such as the United States, China, and Australia, can pump water from wet regions to dry ones, but poor countriesâabove all, those inner-rim nations in the arc of instabilityâcannot. Trouble may be looming if temperatures resume their upward trend in the next few decades.

The greatest uncertainty, though, is that climate change is an unknown in the fullest sense: scientists simply do not know what will happen next. In 2013, NASA reported that “the five-year mean global temperature has been flat for a decade” (

Figure 7.9

). This might be good news, meaning that temperatures are less sensitive to carbon levels than climatologists had

thoughtâin which case, global warming might stay at the low end of the estimates, adding just 1°F between 1985 and 2035. Or it might be bad news, meaning that the carbon-climate relationship is more volatile than had been thoughtâin which case, temperatures will suddenly spike up from their 2002â12 plateau. Few scientific debates have so much strategic significance, but, in what might be a sign of more uncertainty to come, budget cuts forced the CIA to close its Center on Climate Change and National Security at the end of 2012, just days before the

Global Trends 2030

report was published.

Figure 7.9. Strategic science: NASA estimates of global warming, 1910â2010. The gray line shows the average annual temperature and the black line the five-year running average, whichâto many scientists' surpriseâhas flattened off since 2002.

But in spite of all this doom and gloom, the National Intelligence Council remains relatively optimistic about the outlook as far forward as 2030, the end point of its study. The globocop will probably face mounting financial pressures but will still be able to do its job; consequently, while “major powers might be drawn into conflict, we do not see any ⦠tensions or bilateral conflict igniting a full-scale conflagration.” Further, the potential death toll from great-power conflicts is currently declining. There are no longer enough nuclear warheads in the world to kill us all: an all-out nuclear exchange in the mid-2010s might kill several hundred million peopleâmore than World War II, but much less than the billion-plus whose lives hung in the balance when Petrov had his moment of truth. And as the

2010s go on, the scale of possible slaughter will probably fall further. All the great powers (except China) plan more nuclear reductions, and in 2013 the United States ruled out any possibility of short-term rearmament by putting its new Los Alamos plutonium production facility on hold because of money problems.

As well as getting scarcer, warheads have gotten smaller. The bomb is a seventy-year-old technology, invented in an age when explosives tossed out of the back of a plane were lucky to land within half a mile of what they were aimed at. Multimegaton blasts solved the targeting problem by leveling entire cities, but today, when precision-guided munitions can strike within a few feet of their intended victims, these huge, expensive hydrogen bombs look like a solution to a problem that no longer exists. Accurate, low-yield nuclear warheadsâor even smart conventional bombsâhave largely replaced them.

Even more remarkably, the computers that make smart bombs possible are also giving us antimissile defenses that actually work. There is still a long way to go, and no shield could currently hold off a serious attack by hundreds of missiles equipped with decoys and countermeasures; but in sixteen tests since 1999, the U.S. Ground-Based Midcourse Defense system hit half of the ICBMs sent against it. In November 2012, Israel's Iron Dome system did better still, shooting down 90 percent of the slower, short-range rockets fired from the Gaza Strip (

Figure 7.10

).

Figure 7.10. Iron Dome: an Israeli antimissile missile on its way to shoot down an incoming rocket over Tel Aviv, November 17, 2012

In the next decade or two, the computerization of war will go much further, andâinitially, at leastâalmost everything about it will make war less bloody. When the Soviet Union tried to suppress Afghan insurgents in the 1980s, it shelled and carpet bombed their villages, killing tens of thousands of people. Since 2002, by contrast, the United States has handed over more and more of its own counterinsurgency in that country to remotely piloted aircraft. Like precision-guided missiles, dronesâas they are commonly called

8

âare cheaper than alternative tools (about $26 million for a top-of-the-line MQ-9 Reaper as against an anticipated $235 million for an F-35 fighter) and kill fewer people. Estimates of civilian deaths from drone strikes in Afghanistan and Pakistan have become a political football, and

vary from the low hundreds to the low thousands, but even the highest figures are much lower than the carnage any other method of going after the same targets (say, by using Special Forces or conventional air raids) would have produced.