What Hath God Wrought (100 page)

Read What Hath God Wrought Online

Authors: Daniel Walker Howe

Tags: #History, #United States, #19th Century, #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies), #Modern, #General, #Religion

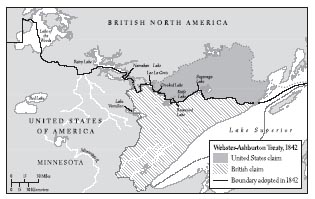

Maine–Canada boundary

Minnesota–Canada boundary.

Tyler felt encouraged by the success of the Webster-Ashburton negotiations to press for a larger accomplishment in foreign policy. Although stymied on the domestic front by congressional Whigs, the president had much more scope for achievement in foreign affairs. He sensed that the American public could be aroused to enthusiasm for westward expansion, and he determined to make Texas annexation his cause. Ideally, he could ride the issue into the White House for another term, this time in his own right. Webster’s long-standing opposition to the annexation of slaveholding Texas now surfaced as a difficulty between him and Tyler, and the two parted ways. But the president had learned a lot from the somewhat devious means that Webster employed to secure approval of his treaty with Ashburton. He would resort to secrecy and government propaganda on a far more extensive scale as he manipulated public opinion regarding Texas annexation.

To succeed Webster at the State Department Tyler appointed Abel Upshur, a proslavery radical of the Calhoun school. Like many other slaveholders, John Tyler regarded Britain with deep ambivalence. The textile mills of Yorkshire and Lancashire constituted an essential customer for southern cotton. Yet Britain also headquartered the international antislavery movement. Having used Webster to resolve many of the outstanding disputes between the United States and Britain, Tyler now turned to Upshur to confront the menace of British abolitionism in Texas. Tyler hoped to win over Calhoun’s faction for his presidential bid. Promoted by the Tyler administration, the issue of Texas annexation replaced state rights as the political mantra of southerners who embraced the new doctrine of the “positive good” of slavery.

The president had already sent the Calhounite newspaperman Duff Green to Europe with a kind of roving commission to spy for the White House. Green’s cover was that of a businessman seeking British venture capital. Green found Lewis Cass a congenial Anglophobic spirit and worked with him to frustrate British efforts for international cooperation in suppressing the Atlantic slave trade. Once Webster left the administration, no one in Washington tried to counteract the reports Green sent back about British plots to “abolitionize” Texas, that is, to guarantee payment of Texan national bonds in return for compensated emancipation. Then, Green warned, Texas would become a magnet for runaway slaves much as Florida had been before 1818, and (somehow) it would all end up with emancipation and race war in the United States. The Texan diplomatic representatives in Washington felt in no hurry to deny these rumors, sensing that they enhanced the value of Texas in the eyes of Tyler’s administration. In fact, the American abolitionist Stephen Pearl Andrews was indeed in London and lobbying for British aid to Texas emancipation, but Peel’s Tory ministry was not prepared to embark on any such expensive and risky adventure in altruism. Duff Green had confused the hopes of the World Antislavery Convention (which Andrews attended) with the intentions of Her Majesty’s Government. The official U.S. minister to Britain, Edward Everett, tried to make the distinction clear. But Green’s reports fed Upshur’s preconceptions and expectations; Everett’s did not.

43

Upshur took Green’s exaggerations and alarms to the American public, publishing anonymous articles in the press on the “Designs of the British Government.”

44

Besides expanding the power of the United States, the annexation of Texas, they argued, would also secure southwestern slavery against the bad example of British-sponsored abolition. Arousing the latent Anglophobia of the American public was often good politics. Besides its official organ, the

Washington Madisonian

, the Tyler administration could also count on the largest-selling newspaper in the country, James Gordon Bennett’s

New York Herald

, to echo Green’s warnings about Britain and support American imperialism. To some extent, at least, Tyler’s inner circle believed their own propaganda that slavery was under threat in Texas; Secretary Upshur privately warned a friend to remove his slaves from Texas lest he lose them to emancipation.

45

In September 1843, Upshur initiated secret discussions with the Texan emissary Isaac Van Zandt regarding annexation. At first Texan president Sam Houston remained cool; he preferred to concentrate his diplomatic efforts on winning Mexican recognition of Texan independence, employing the good offices of Britain. The government of Texas gave no indication of fearing the British posed a threat to its system of labor exploitation, but it did worry about renewed warfare with Mexico. Only after the Mexicans had proposed a truce but no recognition did Houston assent to try negotiating annexation with the United States. In secrecy, Upshur and Van Zandt began drafting such a treaty. In January 1844, Upshur informally promised the Texan negotiator that if they signed a treaty of annexation, the U.S. president would dispatch troops to defend Texas against Mexico without waiting for congressional authorization or ratification of the treaty. This understanding proved key in reassuring the Texans.

46

On February 28, 1844, Secretary of State Upshur, along with the secretary of the navy and several other people, were killed when a gigantic naval gun on board the USS

Princeton

exploded during a demonstration firing. A steam-powered warship (then the cutting edge of technology), the

Princeton

, with its big gun sardonically nicknamed “the Peacemaker,” was the pride of the U.S. Navy. The administration had wanted to show off new weaponry prepared for any coming showdown with Mexico over Texas annexation. By the time of the accident, negotiations for annexation had largely been completed. To carry the Texas treaty forward through ratification, President Tyler appointed as his new secretary of state the ultimate Calhounite: the master of Fort Hill plantation himself.

47

On April 12, 1844, Secretary of State Calhoun and the two Texan negotiators formally signed the treaty of annexation. It provided that Texas would become a U.S. territory eligible for admission later as one or more states. Texan public lands would be ceded to the federal government, which in return would assume up to $10 million in Texan national debt. The boundaries of Texas were not specified but left to be sorted out later with Mexico.

48

Ten days later the treaty went to the Senate. Along with it went Calhoun’s official statement of why Texas annexation was essential: a letter from the secretary of state to Britain’s minister to the United States, Richard Pakenham, declaring that the United States acquired Texas in order to protect slavery there from British interference.

49

Although the press had finally discovered the existence of annexation negotiations a month before, the treaty’s provisions remained a state secret. Tyler and Calhoun intended to make them public only after the Senate, in closed executive session, had consented to ratification.

Then the whole thing blew up in the administration’s face. Senator Benjamin Tappan of Ohio, a maverick antislavery Democrat and an opponent of annexation, leaked the treaty to the newspapers on April 27. The same day, Henry Clay and Martin Van Buren, the recognized leaders of the Whig and Democratic Parties respectively, both issued statements opposing immediate annexation of Texas. The Senate censured Tappan but decided to open up much of its deliberation to the public. When Missouri’s Thomas Hart Benton publicly exposed the misinformation from Duff Green on which the administration had justified its policy, he showed that even a western Jacksonian Democrat, an expansionist under most circumstances, opposed the treaty. On June 8, the Senate defeated Texas annexation by 35 to 16. A treaty needs approval by two-thirds of the Senators; this one had not even mustered one-third. The proslavery justification for Texas offered by Calhoun’s letter to Pakenham immediately appealed only to slave-state Democrats, who backed the treaty 10 to 1 (Benton). Infuriated northern Whigs rejected the treaty 13 to 0. Southern Whigs stayed loyal to Clay by opposing it 14 to 1. Northern Democrats, with their strong tradition of placating the slave power, had more difficulty deciding; they split 7 to 5 against, with 1 abstention.

50

Tyler had wanted to unite the country behind Texas annexation (and himself ). What had gone wrong? Like Tyler, John C. Calhoun hoped that 1844 would be his year for the presidency. He had resigned from the Senate thinking to devote full time to campaigning. But the philosopher of state rights had not succeeded in rallying a solid South behind his candidacy and the extreme proslavery paranoia that he represented to the political community. Although some northern “doughface” Democrats came to his support, his refusal to endorse the Dorr Rebellion, popular with most northern Democratic voters, hurt him.

51

Calhoun had pulled out of the race in December 1843, without waiting for the Democratic National Convention. He then seized upon his appointment as Tyler’s secretary of state to implement the same goal he would have pursued as president: to make the federal government explicitly proslavery. When Secretary of State Calhoun avowed the protection of slavery the primary reason for annexing Texas, this was more than most American politicians at the time were willing to swallow. Both major parties had long agreed that Texas annexation seemed too hot to handle. The prolonged secrecy surrounding the treaty proved another tactical mistake, for the northern press turned alienated and hostile when shut out from the news by which it lived.

Calhoun’s presidential candidacy, which he pursued throughout 1842 and 1843, had undercut Tyler’s candidacy, because of course the race had room for only one of them. Still, the Tyler and Calhoun supporters could cooperate against those who wanted to sew the nomination up for Martin Van Buren. Sometimes the lines between the Tyler and Calhoun campaigns blurred. While Tyler thought Upshur was supporting him, in reality the secretary seems to have been working for Calhoun. Very likely Calhoun, Upshur, and their friends, including Senator Robert Walker of Mississippi, played on the president’s vanity, encouraging him to stay in the race to further purposes of their own without feeling any real loyalty to his cause.

52

Having given up entirely on the Whigs, Tyler now hoped for the nomination of the Democratic Party, but that great patronage machine was not about to bestow its highest prize on an interloper. Why should the Democrats make an exception to their cherished value of party solidarity and loyalty? They benefited more by insisting that Tyler remained a Whig and that the Whigs were therefore hopelessly divided among themselves. Clinging desperately to his dream of a second term, Tyler took up the third-party option and organized a convention, consisting mostly of federal officeholders, who went through the motions of nominating him but did not provide him with a running mate.

Looking back afterwards, Tyler grumbled that his presidential bid had been hurt by the insistence of his secretary of state on making the Texas treaty an explicitly proslavery measure.

53

But, if it did Tyler’s candidacy no good, Calhoun’s tactic served another purpose. By identifying Texas with slavery, Calhoun made sure that Van Buren, being a northerner, would have to oppose Texas. This, Calhoun correctly foresaw, would hurt the New Yorker’s chances for the Democratic nomination. Nor did the Carolinian’s ingenious strategy ultimately wreck the cause of Texas annexation. Indeed, in that respect it would turn out a brilliant success.

54

III

The election of 1844 was one of the closest and most momentous in American history. The Whig Party met for its national convention in Baltimore on May 1. No one had the slightest doubt that the presidential nomination would go to Henry Clay, and so it did, unanimously. As a gesture of confidence in Whig judgment, the nominee allowed the convention freedom to choose his running mate. The southern delegates felt that, to balance the ticket, a northern evangelical should get the nod. The view prevailed, and the vice-presidential choice went to New Jersey’s former senator, Theodore Frelinghuysen, president of the American Bible Society and the American Tract Society, befriender of the Cherokees, sabbatarian and temperance advocate, nicknamed “the Christian statesman.” Clay expected his opponent to be Martin Van Buren and that the campaign would be fought along the economic lines that had emerged during the past fifteen years: the American System and a national bank versus laissez-faire and banking rules left up to the states. With Texas annexation clearly heading for defeat in the Senate, it did not seem likely to figure in the campaign. Van Buren had paid a courtesy call on Clay at Ashland in May 1842, and many people, both in their own day and since, have supposed the prospective candidates there reached an informal agreement, as Unionists and gentlemen, to leave Texas out of their contest. Very likely, however, the two reached the same conclusion independently and their simultaneous announcements were a coincidence.

55