What Hath God Wrought (99 page)

Read What Hath God Wrought Online

Authors: Daniel Walker Howe

Tags: #History, #United States, #19th Century, #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies), #Modern, #General, #Religion

Jackson maintained a facade of neutrality between Texas and Mexico out of regard for his vice president. Van Buren knew that northerners regarded Texas as an outpost of slavery they did not wish to acquire, and he realized that the issue could complicate his election in the fall of 1836. Once the election had safely passed, Jackson began to push hard for the settlement of debts Mexico owed U.S. citizens. Not all the claims were well founded, but they provided leverage to pressure the financially strapped Mexican government into accepting some American money in return for surrendering Texas. On his last day in office, March 3, 1837, Old Hickory officially recognized the independence of Sam Houston’s government.

Discussions regarding Texas annexation then proceeded within the Van Buren administration until cut short in 1838, when John Quincy Adams got wind of them. Adams brought the issue to public attention, whereupon the cautious Fox backed away from a storm of northern protest.

31

Van Buren handled Texas the same way he handled the crisis across the northern border in Canada. Ontario too had attracted settlers from the United States, who also made trouble for their foreign government and talked a lot about turning over their province to their native country. But Van Buren preferred conciliation to confrontation and peace to war. He had learned the arts of regional politics in his home state, where the racist workingmen and proslavery cotton merchants of New York City had to be balanced against the antislavery sentiments upstate. Texas annexation was one concession the South did not get from Jackson’s otherwise compliant successor.

II

Texas remained an independent republic for ten years. Immigration from the United States soared during the recurrent hard times that began in 1837, as southwesterners sought to escape their debts and start over in a new country where slavery had now been legalized. By 1845 the population of Texas reached 125,000, representing an increase of 75,000 in a decade. Over 27,000 of these inhabitants were enslaved, most of them imported from the United States but some from Cuba or Africa. Although the law forbade export of U.S. slaves to foreign countries, no one enforced the prohibition along the Texas/Louisiana border, either before or after Texan independence. The slave population grew even faster than the free population in the Lone Star Republic. Even if slavery did not actually trigger the Texan Revolution, the revolution’s success certainly strengthened the institution in Texas.

32

During this time the Texan government pursued a dual foreign policy. On the one hand, annexation by the United States constituted an obvious objective. It offered military security against reconquest by Mexico, as well as improved economic prospects. The decade of Texan independence included the depression years following 1837, and, like the Mexican Republic from which it separated, the Lone Star Republic suffered from a chronic shortage of capital, both public and private. Bondholders of the impecunious new entity hoped the United States could be persuaded to annex not only Texas but also the Texan national debt. Land speculators, always influential in Texan politics, rejoiced that independence had stepped up the rate of immigration and figured (correctly) that annexation would boost it further. On the other hand, however, the dream of a strong independent Texas held attraction too, particularly if the Lone Star Republic could expand to the Pacific and become a two-ocean power. In this scenario, Britain might provide economic and military aid as a substitute for help from the United States. The emphasis in Texan foreign policy goals shifted now one way, now the other. Although the two policies envisioned alternative futures, in practice they proved quite compatible, since the prospect of an independent Texas allied with Britain alarmed U.S. authorities, encouraging them to overcome northern opposition to annexation. Even now it is by no means clear when Texan statesmen like Sam Houston were courting British aid to achieve long-term Texan independence and when they were doing it to get the attention of policymakers in Washington.

The British really did have an interest in Texas, though not so strong a one as the Texans hoped or the Americans feared. British commercial interests welcomed the prospect of trade with Texas as an alternative source of cotton imports. From a geopolitical point of view, an independent Texas sharing the North American continent might make the aggressive, troublesome United States less of a threat to the underpopulated dominions of British North America. But what shaped British policy the most was the interest of British bondholders. Since British citizens had invested in Texas and to a much greater extent in Mexico, their government hoped to promote stability and solvency in both Mexico and Texas by encouraging the two countries to make peace on the basis of Texan independence. Finally, Britain’s strong antislavery movement aspired to wean the Texans away from the practice of slavery, or at least from the international slave trade, as the price of British aid.

33

This prospect considerably heightened the anxiety felt by President Tyler and certain other southern politicians.

Tyler’s secretary of state, Daniel Webster, had a different perspective on Anglo-American relations. A Whig supporter of internal improvements, like most members of his party he looked upon Britain as an essential source of investment capital, particularly important in 1842 for helping the United States pull out of its depression and resume economic development.

34

To negotiate outstanding difficulties between the two countries, Prime Minister Robert Peel sent Lord Ashburton, retired head of the investment banking firm of Baring Brothers. Baring’s had extensive experience in what the British call “the States,” and Ashburton had married an American. He and Webster knew and respected each other. But the list of issues confronting them tested the resourcefulness of even these skillful and well-motivated negotiators.

The

Caroline

incident in Van Buren’s administration constituted the first such issue. This conflict came back into the news when the state of New York put an alleged Canadian participant in the raid on trial for arson and murder. Fortunately for all parties, the jury acquitted him. Webster and Ashburton dealt with the

Caroline

through an exchange of letters. Webster declared that an attack on another country’s territory is legitimate only when a government can “show a necessity of self-defence, [

sic

] instant, overwhelming, leaving no choice of means, and no moment for deliberation.”

35

Ashburton replied that he accepted this standard and thought the circumstances had met it. He added, however, that it was too bad the British had not promptly offered an explanation and apology. Webster seized upon the word “apology” and declared American honor satisfied; he filed no claim for damages. Webster’s definition of international law on the subject was cited at Nuremberg and during the Cuban Missile Crisis to define situations when preemptive strikes may or may not be justified as self-defense.

36

Another international incident had arisen in 1841, resembling in some respects the case of the

Amistad

. This involved the American brig

Creole

, which sailed from Hampton Roads, Virginia, with a cargo of 135 slaves bound for the markets of New Orleans. On November 7, the slaves rebelled, killed one of their owners and wounded several crew members, then sailed the ship into the port of Nassau in the Bahamas, a British colony where slavery had been illegal since 1833. There they came ashore to the cheers of assembled black Bahamians. The local authorities pronounced the refugees free and decided against prosecuting anyone for murder. When the news reached Washington, the abolitionist Whig congressman Joshua Giddings declared the mutineers on the

Creole

had been fully justified in asserting their natural right to freedom. Formally censured for this by the House of Representatives, Giddings felt vindicated after his antislavery constituents reelected him in a landslide. Angry American slaveholders demanded their property back, and to placate them Webster had to pursue financial compensation. Ashburton agreed to refer the matter to an international commission, which in 1853 awarded the masters $110,000 from the British government.

37

Ashburton wanted the United States to accept the right of the Royal Navy to board ships suspected of engaging in the outlawed Atlantic slave trade. So long as the United States withheld such authority, slave traders from other countries flew the Stars and Stripes to deter detection. But Lewis Cass, the ambitious Michigan Democrat who served both Van Buren and Tyler as minister to France, complained loudly that the British were trying to revive their old practice of impressing sailors on American ships; his demagogy prevented Webster from agreeing to the British proposal, although several other nations did consent. Instead, the United States promised to maintain a squadron of its own to patrol for slave traders, a commitment honored only halfheartedly by the Democratic administrations that controlled the federal government most of the time until the Civil War.

38

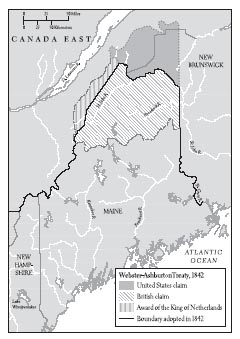

The boundary dispute between the United States and Canada, stemming from the vagueness of the Treaty of 1783 and the geographical ignorance of that time, required resolution in a formal treaty. The most hotly contested portion of the boundary lay between Maine and New Brunswick. One attempt to resolve it, through Dutch mediation in 1831, had already failed. In February 1839, the militias of Maine and New Brunswick had come dangerously close to an armed clash. The intransigence of the state of Maine, which had been granted the right to veto whatever the federal government negotiated, made compromise particularly difficult. Webster worked to soften Maine’s attitude by a combination of lobbying state legislators and publishing newspaper articles favoring compromise, paying for both out of secret executive funds that Congress had authorized for foreign affairs. Expending the money to influence American public opinion was something of a stretch but not forbidden by the law. To help convince key Maine individuals to accept compromise, Webster also showed them in confidence an early map assigning the whole disputed area to New Brunswick, suggesting that the American bargaining position would not bear close examination and that compromise was the only prudent course. In fact, a number of such early maps existed, showing a variety of boundaries; indeed, back in London, the foreign secretary possessed one that seemed to substantiate the American claim. The bargain that Webster and Ashburton eventually struck awarded Maine seven thousand square miles and New Brunswick five thousand square miles of the disputed area, and the states of Maine and Massachusetts (which Maine had been part of until 1820) signed off on it in return for $125,000 each from the British government.

39

The boundary as finally agreed substantially coincided with the compromise that the Dutch king had proposed back in 1831. Webster might have been able to get more territory for Maine by more diligent searching for early maps, but he judged mutual conciliation more important than any of the particular issues. As he explained to his friend, the capable U.S. minister in London, Edward Everett: “The great object is to show mutual concession and the granting of what may be regarded in the light of equivalents.” History seems to have vindicated the work of Webster and Ashburton: Their peaceful compromise of the unclear boundary has proved a durable resolution.

40

The Webster-Ashburton Treaty also demarcated the northern boundary of Minnesota more clearly. The line it drew, although the subject of less controversy at the time, proved ultimately more significant. It assigned the United States the rich iron ore, discovered many years later, of the Mesabi and Vermillion Ranges. Ashburton had no way of knowing the importance of the concession he made.

41

The Webster-Ashburton Treaty of 1842 represented a temporary confluence of interest between Tyler and the Whigs. “His Accidency” had long been an ardent and consistent expansionist. At this moment, he wanted to resolve tensions with the British in order to minimize their opposition against his intended annexation of Texas. For their part, the Whigs wanted access to British capital for American economic recovery and development; this explains why the Whig-dominated Senate consented to the treaty’s ratification on August 20. While vetoing Whig plans for a third Bank of the United States, Tyler had his own project to alleviate the depression, at least for some hard-pressed southern planters. Annexing the fertile cotton lands of Texas would ensure that their slave markets stayed open and busy, bidding up the value of all slaveowners’ property. The depression had also influenced the British government in its search for an accord with the United States. Responsive as usual to the interests of their bondholders, they hoped to persuade the federal government to assume the debts of states that had defaulted on their bonds. But the hope proved vain.

42