What Hath God Wrought (98 page)

Read What Hath God Wrought Online

Authors: Daniel Walker Howe

Tags: #History, #United States, #19th Century, #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies), #Modern, #General, #Religion

Travis and his men were no suicidal fanatics. They defended the Alamo in the belief that they had rendered it defensible until the reinforcements they had requested could arrive. Santa Anna showed up on February 22, 1836, sooner and with a larger force than they had anticipated. Travis dispatched Seguín to urge the force at Goliad to come to his aid as soon as possible. On March 5, only a handful of reinforcements having arrived, Travis recognized the hopelessness of the situation. He convened a meeting and told the occupants of the Alamo they could leave if they thought they could escape through the Mexican siege lines. Maybe he drew a line in the sand with his sword—such a dramatic gesture would not have been out of character. Santa Anna had raised the red flag that signaled no quarter. But only one man and a few of the noncombatant women took up Travis’s offer.

16

Santa Anna did not need to storm the Alamo. His biggest cannons, due to arrive soon, would readily breach its walls. His intelligence reported no reinforcements on their way to the Alamo and that the defenders, weakened by dysentery, had little food or potable water left. The dictator ordered an assault for March 6 lest a Texan surrender rob him of a glorious victory. His assault force of fifteen hundred fought their way in and killed the defenders, suffering very heavy casualties themselves. The last half dozen Texans were overpowered and taken prisoner by a chivalrous Mexican officer who intended to spare their lives. Santa Anna entered the Alamo only after the fighting had ended, when he would be safe. He ordered the prisoners killed, whereupon they were hacked to death with swords. Mexican Lieutenant José Enrique de la Peña, who admired his enemies’ courage as much as he despised his own commander, noted that the men “died without complaining and without humiliating themselves before their torturers.” De la Peña believed Crockett to be among this group, and historians now generally accept his testimony.

17

The defenders of the Alamo against overwhelming odds passed into the realm of heroic epic, along with the Spartans at Thermopylae and Roland at Roncesvalles.

Not quite everyone captured in the Alamo was killed. Santa Anna spared some noncombatant

tejana

women, probably in a bid for Hispanic support, two black slaves of William Travis, perhaps to encourage other bondsmen to desert his enemies, and Suzanna Dickenson, widow of a Texas officer, so she could spread the word of the horrible fate awaiting those who resisted

el presidente

. His unnecessary attack had cost his best battalions one-third of their strength. But the dictator cared so little for his soldiers that he did not bother to set up a field hospital and allowed, his secretary noted bitterly, over one hundred of his wounded to die from injuries that could have been successfully treated.

18

At Goliad, the Texan commander James Fannin hesitated, then decided not to go to the aid of the Alamo. Goliad seemed at least as important to hold, he reasoned. But Fannin’s force wound up surrounded by a much larger Mexican army and surrendered. General Urrea left his prisoners with another officer, instructed him to treat them decently, and continued his advance. Santa Anna, upon learning of their capture, sent a message commanding the execution of Goliad’s defenders. On March 27, Fannin and 341 of his men were accordingly massacred; 28 managed to escape.

19

In size and circumstances, this constituted an atrocity even worse than that at the Alamo.

Up in East Texas, where most Anglos lived, many wanted to declare full independence from Mexico, and events played into their hands. The pro-independence party enjoyed its greatest strength among the most recent arrivals and among substantial slaveholders, who feared they could not continue indefinitely to get around the Mexican laws against slavery. Stephen Austin and other Anglo-Texans who had flourished under the Mexican Constitution of 1824 were less radical; the newcomers called them “Tories.”

20

The outbreak of fighting produced a sudden influx of Anglo males from the United States; to these new men, the Mexican Constitution of 1824 held no meaning, and nothing but independence made any sense as a goal. Since the newcomers provided some 40 percent of the armed force Texas could put into the field, their views carried weight. The cause of Texan independence enjoyed popularity in the United States, where many viewed it as a step toward annexation. Independence would make it easier for Texas to raise men and money in the United States, just as the American Declaration of Independence in 1776 had facilitated help from France. Besides, as Stephen Austin explained, “The Constitution of 1824 is totally overturned, the social compact totally dissolved.” On March 2, 1836, while the siege of the Alamo continued, a Texan Convention proclaimed independence from Mexico and issued a declaration carefully modeled on Jefferson’s.

21

By the seventeenth, this body had drafted a national constitution modeled on that of the United States and sanctioning chattel slavery; a referendum ratified the constitution in September. The Convention also chose David Burnet first president of the Texan Republic and balanced the ticket with a Hispanic vice president, Lorenzo de Závala.

Before independence, political lines in Texas had not coincided with linguistic ones. Most Texans, Anglo and Hispanic alike, had been

federalistas

. Among the few

centralistas

there were even Anglos like Juan (originally John) Davis Bradburn, a former Kentuckian who rose high in the Mexican army. Texan independence disadvantaged

los tejanos

, putting them in the strange position of a minority group in their own land. Most of them had felt more comfortable fighting for the Constitution of 1824. Some of the

rancheros

joined with the Mexican army as it passed through their neighborhood. Other

tejanos

, including the Seguíns, embraced Texan independence and fought for it. Even so, many Anglos, especially those newly arrived, distrusted the loyalty of any Hispanic. Almost all Anglo-Texans had come from the southern section of the Union and brought with them a commitment to white supremacy. Now, many waged the revolution as a race war against a

mestizo

nation.

22

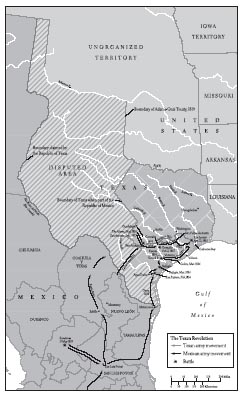

Following their victories at the Alamo and Goliad, the Mexican armies continued their advance northward, intending to complete their destruction of the insurgency and drive whatever might be left of it across the Sabine into the United States. Now commanded by Sam Houston, the Texan army withdrew before them, as did many Anglo civilians in what they called “the Runaway Scrape.” Houston continued his retreat well into East Texas, making sure that the next battle would take place on his army’s familiar home ground, where the wooded environment suited his tactics better than the open country that favored the Mexican cavalry. His undisciplined soldiers complained constantly that they should stand and fight, but the outcome vindicated their commander. Santa Anna, trying to find and fix his antagonist, divided his army so that each component could search separately. In doing so he committed a classic tactical mistake, enabling Houston to attack the detachment accompanying Santa Anna with something approaching even odds. When the Texans intercepted a Mexican courier and found Santa Anna’s troop dispositions in his saddlebags, Houston saw that his moment had arrived.

The battle occurred on 21 April 1836, inside Stephen Austin’s land grant, not far from the present-day city of Houston and near a river named San Jacinto (“hah-

seen

-toe” in Spanish, but Texans say “ja-

sin

-tah”). With a negligence that equaled his immorality, Santa Anna had failed to provide local security while his tired soldiers rested. Houston’s men charged, shouting “Remember the Alamo!” The surprised Mexicans fled, only to be slaughtered by Texans in no mood to take prisoners. General Houston, defying a broken ankle, along with Texas secretary of war Thomas Rusk, tried in vain to command their men to obey the laws of war; in the words of a judicious historian, “the bloodthirsty rebels committed atrocities at least as beastly as those the Mexicans had committed.”

23

The next day, military order restored, those enemy soldiers lucky enough to have survived were rounded up as captives. All told, the Mexicans lost about 650 killed and 700 prisoners at San Jacinto—virtually all the men they had engaged.

Among the prisoners, Santa Anna himself turned up. Instead of treating him as a war criminal (a status not then defined), Houston shrewdly bargained with the captured dictator. In return for his life and a safe conduct, Santa Anna promised that the Mexican army would withdraw beyond the Rio Grande (also called the Rio Bravo and Rio del Norte), even though the Nueces River, 150 miles farther north, had always been the boundary of Texas in the past. Accordingly, Santa Anna sent his successor in command, General Vicente Filisola, an order to evacuate Texas. Filisola obeyed, despite the remonstrance of General Urrea and others; he had come far from his supply base, and his financially strapped government had warned that no more resources could be devoted to the campaign. As the Mexican armies withdrew, they were joined by fugitive slaves and those Hispanic civilians who did not choose to cast their lot with an independent Texas. The document forced upon Santa Anna included a provision for the restoration of runaway slaves to their Anglo owners, but it proved impossible to enforce this.

24

The Texans considered the Velasco agreement signed by Santa Anna and Texas president David Burnet a treaty recognizing their independence; the Mexican Congress, however, refused to approve it on the understandable grounds that it had been extorted from a captive who had every reason to expect death if he did not consent. Intermittent warfare between Texas and Mexico continued for years. Mexican armies twice reoccupied San Antonio (in the spring and fall of 1842) but could not retain the town. The Texans tried to make good on their extravagant claim that the Rio Grande constituted their western boundary from mouth to source. They set up their national capital at Austin, rather than more logical places like Galveston or Houston, as a symbol of their westward aspirations.

25

But several expansionist Texan offensives, including attempts to capture Santa Fe in 1841 and 1843, and an expedition to Mier on the Rio Grande in 1843, all failed completely. As a result, the Nueces remained the approximate de facto limit of the independent Lone Star Republic, except for the town of Corpus Christi where the Nueces met the Gulf. (The famous Lone Star Flag of Texas, suggested by emigrants from Louisiana, derived from the flag of the 1810 Baton Rouge rebellion against Spanish West Florida, which had featured a gold star on a blue background.)

26

In October 1836, Sam Houston won the Texan presidential election in a landslide. Stephen Austin, who also ran, already seemed a voice from the past; he died soon afterwards. Juan Seguín found himself betrayed by the Anglos he had once fought alongside. Persecuted, he and his family fled to Mexico; when the next war came, he fought on the Mexican side against the United States. Santa Anna, disgraced by his conduct in Texas, fell from power in Mexico, regained it after redeeming himself fighting a French invasion of his country in 1838–39 at the cost of one of his legs, then lost power again in 1844 to the liberal José Herrera.

In the United States, Sam Houston’s longtime personal friend Andrew Jackson professed official neutrality while not actually preventing the Texans from obtaining men, munitions, and money for their cause. He also dispatched U.S. troops to the Sabine—and even across it—as an implied warning to Mexico that the reconquest of Texas could lead to conflict with the United States.

27

The Mexicans wrongly assumed that Jackson had fomented the rebellion; in fact, he worried that Texan independence might complicate his efforts to annex the region. They rightly perceived, however, his intention to obtain Texas for the United States. As early as 1829, Jackson had instructed his tactless, incompetent diplomatic representative in Mexico City, Anthony Butler, to try to acquire Texas, bribing Mexican officials if necessary. Not until April 1832 did the United States and Mexico exchange ratifications of a treaty affirming that the border defined between the United States and Spain in 1819 would continue to apply.

28

After the Battle of San Jacinto, Jackson actually met with the defeated Santa Anna, then eager to ingratiate himself with the Americans, and made him an offer to buy Mexico’s claim to Texas for $3.5 million, but that ultimate opportunist no longer spoke for the Mexican government.

29

Jackson’s attitude toward Texas fit with his foreign policy in general, which was largely a projection of his personal experience. As a planter and land speculator, he took an interest in the expansion of cotton acreage and in securing overseas markets for agricultural staples. Indian Removal, foreign trade agreements, and Texas annexation all reflected these interests. A soldier renowned for his defense of New Orleans, he remained concerned with the strategic security of the Southwest and now wanted the border pushed far beyond the Sabine (although he had favored the boundary of Adams’s Transcontinental Treaty when President Monroe asked his opinion).

30