What Hath God Wrought (105 page)

Read What Hath God Wrought Online

Authors: Daniel Walker Howe

Tags: #History, #United States, #19th Century, #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies), #Modern, #General, #Religion

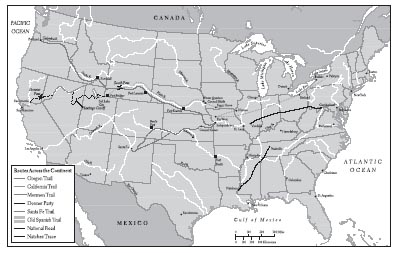

With transportation of heavy goods upstream on the Missouri laborious and the trip around Cape Horn taking six to eight months, the practicality of maintaining U.S. control over distant Oregon had been doubted by prominent statesmen of both parties—Albert Gallatin, Daniel Webster, and Thomas Hart Benton among them. More recent developments had altered this expectation: the negotiation of the overland route with wagons, the development of the railroad, and the invention of the electric telegraph. Now it seemed that if Americans settled in the Pacific Northwest, they could remain within the United States. By the end of 1844 some five thousand Americans had relocated to Oregon—far fewer than lived in Texas but more than lived in California and enough to have an impact. By comparison, only seven hundred British subjects then lived in the condominium, most of them not permanent settlers but on temporary assignment for their employer. For thirty years the British had been more active in Oregon than the Americans; now the new arrivals tipped the balance in favor of the United States.

29

Practically all the migrants arriving along the Oregon Trail chose to settle in the Willamette Valley, a fertile area south of the Columbia River that they felt reasonably certain would be assigned to the United States even if Oregon was eventually partitioned between the two occupying powers. There they set up an unauthorized but functioning local government of their own. During these years, many settlers also left the British Isles to pioneer colonies overseas, but they headed mainly for Australia and New Zealand. Some Canadians, retired HBC employees, had settled early in the Willamette Valley, but more recent American arrivals threatened to drive them out. These American settlers were no longer New England missionaries but mostly Missourians, a tough people little restrained by legalities, who had ruthlessly expelled the Mormons from their home state. The Americans included former trappers bitter at the HBC for its cutthroat competitive practices. The possibility of violence in Oregon could not be ruled out.

30

Not coincidentally, relations with the Indian tribes revealed conflicting interests between the occupying powers. HBC valued the natives as customers and suppliers of otter and beaver pelts, and it willingly sold them firearms; U.S. settlers wanting to expropriate Native lands regarded such sales as an invitation to frontier warfare.

The Hudson’s Bay Company tried to cultivate good relations with its new neighbors, extending them credit to purchase supplies. The settlers took the supplies and never paid for them.

31

Becoming concerned for the safety of its valuable inventories with a potentially hostile population nearby, HBC closed down Fort Vancouver in 1845 and shifted its base of operations to Fort Victoria at the site of the present city of Victoria, British Columbia. The international fur trade was beginning its decline, due to both diminishing supply and diminishing demand, and this persuaded Sir George Simpson, chief of HBC’s Oregon operations, that prospective profits did not justify mounting a challenge to the American settlers. In preparation for the move northwards, the Hudson’s Bay Company trapped out the southern portion of the Oregon territory, leaving the beaver there virtually extinct.

32

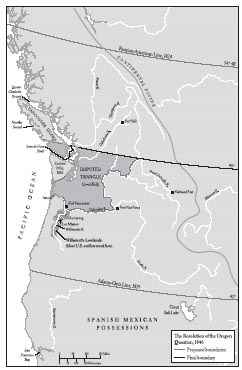

The Democratic platform of 1844, with its call for the whole of Oregon, ignored the fact that the British and American governments had long assumed that Oregon would eventually be divided between them and had discussed how that division should go. The British had proposed that the existing 49th parallel boundary be extended west to the Columbia River, at which point the boundary should follow the Columbia to the sea. The Americans had proposed that the 49th parallel should simply be extended due west, all the way across Vancouver Island. Thus, of all the great Oregon Territory, only the area between the Columbia River and the 49th parallel remained in serious dispute. Historians refer to this area as “the disputed triangle,” although it is only vaguely triangular. Within the disputed triangle, the Hudson’s Bay Company carried on virtually all white activity.

Throughout his negotiations concerning Oregon, President Polk played a double game. While seeming to demand all of the Oregon country for the United States, in reality he revealed a willingness to compromise, provided he could get most of the core disputed triangle. A peaceful settlement with Britain over Oregon would ensure that she would not come to Mexico’s aid when he forced a showdown with that country over California. John Tyler, who had concluded the Webster-Ashburton Treaty to smooth the way for annexing Texas, provided Polk with a model: conciliating Britain facilitated getting tough with Mexico. Young Hickory attached much more importance to California than to what is now British Columbia.

Polk could not afford the political embarrassment of overtly betraying the Democratic platform of 1844, which had played such a prominent role in the campaign. The Missouri congressional delegation for a time stimulated American interest in Oregon, since their state, anchoring the east end of the Oregon Trail, provided not only many of the settlers but most of their supplies and equipment. Migration to Oregon made good business for Missouri. But the majority of the Democrats who rallied to the slogan “Fifty-four Forty or Fight” (an allusion to the latitude of the northern boundary of the Oregon condominium, which was also the southern boundary of Russian Alaska) came from the free states. To alienate them would cost Polk congressional votes he needed for the rest of his program. Northern and western Democrats had proved indispensable to the annexation of all Texas, with its vastly exaggerated boundary claims. In return many of them felt entitled to administration support for all Oregon. Polk therefore had to play his cards in such a way as to achieve a compromise over Oregon without having to accept responsibility for that compromise. In this he succeeded, although in the end the northern Democrats finally did rebel at his manipulations. One of them, Gideon Welles of Connecticut, who served as civilian head of the navy’s logistics bureau during the Mexican War, concluded that Polk had “a trait of sly cunning which he thought shrewdness, but which was really disingenuousness and duplicity.”

33

Already during the Tyler administration, the capable U.S. envoy in London, Edward Everett, had suggested a compromise boundary that followed the 49th parallel except for leaving all of Vancouver Island in Canada—essentially the same line that would finally be agreed. However, Secretary of State Calhoun put the Oregon negotiations on hold while he concentrated his attention on Texas. With a continuing influx of American settlers into Oregon, he reasoned, time was on the side of the United States. President Tyler took little interest in Oregon compared with Texas and would probably have been willing to accept partition of the condominium along the Columbia River line.

34

When Polk came into office, he replaced Everett (a Webster Whig) with another experienced and knowledgeable emissary to London: Louis McLane, the successful negotiator of Jackson’s commercial treaty with Britain, former secretary of state and Treasury, now president of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. This strong appointment signaled Polk’s willingness to work toward a mutual understanding over Oregon. Lord Aberdeen, Britain’s foreign secretary, sent Richard Pakenham as his emissary to Washington. A cousin of the Edward Pakenham whom Jackson had defeated at New Orleans, he proved a less happy choice of envoy than McLane. Fundamentally, the Foreign Office favored good relations with the United States. The Peel ministry intended to repeal the “Corn Laws,” Britain’s protective tariffs on grain; they knew that Polk too was a free trader resolved to lower the Whig tariff of 1842, and they looked forward to a mutually profitable expansion of Anglo-American trade. But, like Polk, Aberdeen had to look over his shoulder toward domestic politics when conducting diplomacy. The opposition’s shadow foreign secretary, Lord Palmerston, had criticized the Webster-Ashburton Treaty and might denounce any sign of weakness in dealing with the Yankees. So Aberdeen tried to hedge. He gave Pakenham two sets of instructions, an official one to stick firmly by the British position, and an unofficial one to refer an American proposal back to London.

35

After arriving in Washington, Pakenham received in mid-July 1845 an offer from the Polk administration to partition Oregon at the 49th parallel. Polk intended this as the opening gambit in a negotiation; he could excuse his initial failure to insist on 54° 40' by saying that the previous administration had committed the United States to offering such a compromise. Three weeks away from his government’s advice, Pakenham chose to follow his official, rather than his unofficial, instructions. He rejected the American offer out of hand. It was the wrong decision. Once again the slowness of transatlantic communication played havoc with Anglo-American diplomacy; the delicately laid plans of both Polk and Aberdeen had gone awry.

Furious, Polk called upon Congress to pass an act serving Britain with one year’s notice that the United States would terminate the joint occupation agreement in Oregon.

36

This would focus British attention on the need to resolve the matter somehow while according northwestern expansionists full opportunity to vent Anglophobic rhetoric. The Democratic popular press, particularly O’Sullivan’s

Democratic Review

, James Gordon Bennett’s

New York Herald

, and Moses Beach’s

New York Sun

, beat the drums for termination as a prelude to seizing all of Oregon. Polk welcomed the bluster at this stage, hoping it would impress the British, and in the meantime he refused to negotiate with them any further over Oregon. However popular among certain Democratic voters, the president’s belligerency alarmed Wall Street, and stocks fell.

37

Passing the congressional resolution that Polk wanted proved no simple matter, due to opposition from two quarters unwilling to risk a confrontation with Britain: most Whigs, who wanted British investment capital, allied with many southern Democrats, led by Calhoun, who placed a higher value on Britain as a customer for cotton than they did on extra acreage in the Pacific Northwest inhospitable to plantation slavery. A handful of the most antislavery Whigs pressed for all of Oregon as a counterweight to slaveholding Texas.

The British now proposed arbitration, but Polk refused, knowing this would expose him to reproach from those demanding all of Oregon. Though the extremists imagined that they were on the president’s side, the historian can discern indications that this inscrutable executive indulged them and exploited them to prod the British, but did not ultimately share their objective. The administration’s closest collaborator on Oregon in the Senate, Thomas Hart Benton, despite his Missouri constituency, worked with the moderates to add a conciliatory amendment to the termination resolution. Louis McLane corresponded from London with Calhoun as well as Polk, but not with the expansionist chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, William Allen of Ohio. Polk certainly never seriously entertained the possibility of going to war for what is now British Columbia, since he made no military or naval preparations for it. The Peel ministry, by contrast, did prepare. (British leaders worried about having to fight the United States and France at the same time just as Americans worried about having to fight both Britain and Mexico.)

38

One perceptive contemporary saw through Polk’s policy. John Quincy Adams, true to his old expansionist principles as Monroe’s secretary of state, defended the title of the United States to the whole of Oregon, drawing upon his unparalleled knowledge of history and international law, confirmed by the Bible. “I want the country for our western pioneers,” he told the House of Representatives. God’s chosen people had been promised “the uttermost parts of the earth for thy possession” (Psalm 2:8). Yet, Adams correctly predicted, “I believe the present Administration will finally back down from their own ground.”

39

(Indeed, Adams himself, as president, had approved extending the joint occupation agreement when it came up for renewal in 1827.)