Why the West Rules--For Now (33 page)

Read Why the West Rules--For Now Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Tags: #History, #Modern, #General, #Business & Economics, #International, #Economics

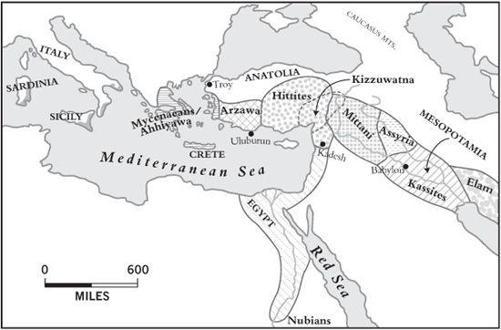

Trade boomed. Royal texts are full of it, and fourteenth-century letters found at Amarna in Egypt show the kings of Babylon, Egypt, and the newly powerful states of Assyria, Mittani, and the Hittites jockeying for position, asking for gifts, and marrying off princesses. They created a shared diplomatic language and addressed one another as “brother.” Second-tier rulers, excluded from the club of great powers, they called “servants,” but rank could be renegotiated. Ahhiyawa (probably Greece), for instance, was a borderline great power. There are no Ahhiyawan letters in the Amarna archive, but when a Hittite king listed “

the kings who

are equal to me in rank” in a thirteenth-century treaty he named “the king of Egypt, the king of Babylonia,

the king of Assyria, and the king of Ahhiyawa”—only to think better of it and scratch Ahhiyawa off the list.

Figure 4.4. The band of brothers: the Western core’s International Age kingdoms as they stood around 1350

BCE

, after the Hittites and Mittani had gobbled up Kizzuwatna but before the Hittites and Assyrians destroyed Mittani. The gray areas in Sicily, Sardinia, and Italy show where Mycenaean Greek pottery has been found.

The more the “brothers” had to do with one another, the tougher their sibling rivalry got. The Hyksos invasion in the eighteenth century

BCE

had traumatized the Egyptian elite, shattering their sense that impassable deserts shielded them from attack; determined to prevent any repeat, they upgraded their rather ramshackle militias into a permanent army with career officers and a modern chariot corps. By 1500

BCE

they had pushed up the Mediterranean coast into Syria, building forts as they went.

An ancient arms race broke out by 1400

BCE

and the devil took the hindmost. Between 1350 and 1320

BCE

the Hittites and Assyrians swallowed up Mittani. Assyria intervened in a Babylonian civil war, and by 1300 the Hittites had destroyed Arzawa, another neighbor. Hittite and Egyptian kings waged a deadly cold war, full of spies and covert operations,

to control Syria’s city-states. In 1274

BCE

it turned hot, and the biggest armies the world had yet seen—perhaps thirty thousand infantry and five thousand chariots on each side—clashed at Kadesh. Ramses II, the Egyptian pharoah, apparently blundered into a trap. Since he was a god, this naturally presented no problem, and in an account posted in no fewer than seven temples, Ramses tells us that he went on a Rambo-like rampage:

His Majesty [Ramses] slew

the entire force of the Foe of Hatti [another name for the Hittites], together with his great chiefs and all his brothers, as well as all the chiefs of all the countries that had come with him, their infantry and their chariotry falling on their faces one upon the other. His Majesty slaughtered them in their places; they sprawled before his horses; and his majesty was alone, none other with him.

The “vile Chief of Hatti,” says Ramses, then begged for peace (as well he might).

Extracting military history from a god-king’s bombast is tricky, but all our other evidence suggests that, contrary to his boasts, Ramses barely escaped the Hittite ambush that day. The Hittites kept advancing down the coast until 1258

BCE

, stopping only because they had picked new fights, one with Assyria in the mountains of southeast Anatolia and another with Greek adventurers on Anatolia’s west coast. Some historians think that Homer’s

Iliad

, the Greek epic poem written down five centuries later, dimly reflects a war in the 1220s

BCE

in which a Greek alliance besieged the Hittite vassal city of Troy; and far to the southeast, an even more terrible siege was under way, ending with Assyria sacking Babylon in 1225

BCE

.

These were savage struggles. Defeat could mean annihilation—men slaughtered, women and children carried into slavery, cities reduced to rubble and condemned to oblivion. Everything, therefore, was sacrificed for victory. More militarized elites emerged, far richer than their predecessors, and their internal feuds took on a new edge. Kings fortified their palaces or built themselves whole new cities where the lower orders would not disturb their tranquillity. Taxes and demands for forced labor rose sharply and debt spiraled as aristocrats borrowed to finance lavish lifestyles and peasants mortgaged harvests to stay alive. Kings described themselves as their people’s shepherds but

spent more time fleecing their flocks than protecting them, fighting to control labor and carrying off whole peoples to work on their building projects. The Hebrews toiling on pharaoh’s cities, distant descendants of Jacob’s sons who had migrated to Egypt with such high hopes, are merely the best known of these slave populations.

So it was that state power grew after 1500

BCE

and the Western core expanded with it. Pottery made in Greece has been found around the shores of Sicily, Sardinia, and northern Italy, suggesting that other, more valuable (but archaeologically less visible) goods were moving long distances too. Archaeologists diving off the Anatolian coast have recovered astonishing snapshots of the mechanics of trade. A ship wrecked at Uluburun around 1316

BCE

, for instance, was carrying enough copper and tin to make ten tons of bronze, as well as ebony and ivory from tropical Africa, cedar from Lebanon, glass from Syria, and weapons from Greece and what is now Israel; in short, a little of everything that might fetch a profit, probably gathered, a few objects at a time, in every port along the ship’s route by a crew as mixed as its cargo.

The shores of the Mediterranean Sea were being drawn into the core. Rich graves containing bronze weapons suggest that village chiefs were turning into kings in Sardinia and Sicily, and texts reveal that young men left their villages on these islands to seek their fortunes as mercenaries in the core’s wars. Sardinians wound up in Babylon and even in what is now Sudan, where Egyptian armies pushed south in search of gold, smashing native states and building temples as they went. Still farther afield, chiefs in Sweden were being buried with chariots, the ultimate status symbols from the core, and were putting other imported military hardware—particularly sharp bronze swords—to deadly use.

As the Mediterranean turned into a new frontier, rising social development once again changed what geography meant. In the fourth millennium

BCE

the rise of irrigation and cities had made the great river valleys in Egypt and Mesopotamia into more valuable real estate than the old core in the Hilly Flanks, and in the second millennium the explosion of long-distance trade made access to the Mediterranean’s broad waterways more valuable still. After 1500

BCE

the turbulent Western core entered a whole new age of expansion.

TEN THOUSAND

GUO

UNDER HEAVEN

Archaeologists often suffer from an affliction that I like to call Egypt envy. No matter where we dig or what we dig up, we always suspect we would find better things if we were digging in Egypt. So it is a relief to know that Egypt envy affects people in other walks of life too. In 1995 State Councillor Song Jian, one of China’s top scientific administrators, made an official visit to Egypt. He was not happy when archaeologists told him that its antiquities were older than China’s, so on returning to Beijing he launched the Three Dynasties Chronology Project to look into the matter. Four years and $2 million later, it announced its findings: Egypt’s antiquities really are older than China’s. But now at least we know exactly how much older.

As we saw in

Chapter 2

, agricultural lifestyles began developing in the West around 9500

BCE

, a good two thousand years earlier than in China. By 4000

BCE

farming had spread into marginal areas such as Egypt and Mesopotamia, and when the monsoons shifted southward after 3800

BCE

these new farmers created cities and states out of self-preservation. The East had plenty of dry, marginal zones too, but farming had barely touched them by 3800, So the arrival of cooler, drier weather did not lead to the rise of cities and states. Instead, it probably made life easier for villagers by making the warm, wet Yangzi and Yellow river valleys a little drier and more manageable. Hard as it is to imagine today, the Yellow River valley was mostly subtropical forest around 4000

BCE

; elephants trumpeted down what are now the car-choked streets of Beijing.

Instead of a transition to cities and states like Egypt and Mesopotamia, fourth-millennium-

BCE

China saw steady, unspectacular population growth. Forests were cleared and new villages founded; old villages grew into towns. The better people did at capturing energy, the more they multiplied and the greater pressure they put on themselves; so, like Westerners, they tinkered and experimented, finding new ways to squeeze more from the soil, to organize themselves more effectively, and to grab what they wanted from others. Thick fortifications of pounded earth sprouted around the bigger sites, suggesting conflict, and some settlements were laid out in more organized ways, suggesting

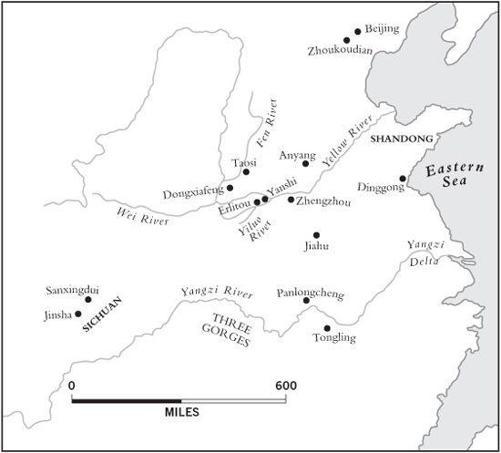

community-level planning. Houses got bigger and we find more objects in them, pointing to slowly rising standards of living; but differences between houses also increased, perhaps meaning that richer peasants were distinguishing themselves from their neighbors. Some archaeologists think that the distribution of tools within houses reveals emerging gender distinctions too. In a few places, notably Shandong (

Figure 4.5

), some people—mostly men—found their last resting place in big graves with more offerings than others, and a few even had elaborate carved jade ornaments.

Beautiful as these jades can be, it must still be hard for archaeologists excavating Chinese sites of around 2500

BCE

to avoid the odd pang of Egypt envy. They find no Great Pyramids or royal inscriptions. Their discoveries in fact look more like what archaeologists find on sites in the Western core that date around 4000

BCE

, shortly

before the first cities and states emerged. The East was moving along a path like the West’s, but at least fifteen hundred years behind; and, staying on schedule, between 2500 and 2000

BCE

the East went through transformations rather like those the West had seen between 4000 and 3500

BCE

.

Figure 4.5. The expansion of the Eastern core, 3500–1000

BCE

: sites mentioned in this chapter

All along the great river valleys the pace of change accelerated, but an interesting pattern emerged. The fastest changes came not on the broadest plains with the richest soils but in cramped spaces, where it was hard for people to run away and find new homes if they lost struggles for resources within villages or wars between them. On one of Shandong’s small plains, for instance, archaeologists found a new settlement pattern taking shape between 2500 and 2000

BCE

. A single large town grew up, with perhaps five thousand residents, surrounded by smaller satellite towns, which had their own smaller satellite villages. Surveys around Susa in southwest Iran found a similar pattern there some fifteen hundred years earlier; this, perhaps, is the way things always go when one community wins political control.

To judge from the lavish send-offs some men got in their funerals, genuine kings may have been clawing their way up the greasy pole in Shandong after 2500

BCE

. A few graves contain truly spectacular jades and one has a turquoise headdress that looks a lot like a crown. The most remarkable find, though, is a humble potsherd from Dinggong. When this apparently unremarkable fragment of gray pottery initially came out of the ground the excavators just tossed it in a bucket with their other finds, but when they cleaned it back at the lab they found eleven symbols, related to yet different from later Chinese scripts, scratched on its surface. Is this, the excavators asked, the tip of an iceberg of widespread writing on perishable materials? Did Shandong’s kings have bureaucrats managing their affairs, like the rulers of Uruk in Mesopotamia a thousand years earlier? Maybe; but other archaeologists, pointing to the unusual way the inscription was identified, wonder whether it has been wrongly dated or is even a fake. Only further discoveries will clear this up. Yet writing or no, whoever ran the Shandong communities was certainly powerful. By 2200

BCE

human sacrifices were common and some graves received ancestor worship.