Why the West Rules--For Now (37 page)

Read Why the West Rules--For Now Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Tags: #History, #Modern, #General, #Business & Economics, #International, #Economics

Like the ancient Western states, the Shang state unraveled rather quickly when things went wrong. The oracle bones suggest that the Shang elite’s internal dynamics had been in turmoil since about 1150

BCE

, leaving the king more powerful but with fewer aristocratic supporters. By 1100 the Shang colonies in the south may have broken away, and many allies closer to home (like the Zhou) had defected.

In 1048

BCE

the Shang king Di Xin could still muster eight hundred lords to block a Zhou attack, but two years later it was a different

story. The Zhou king Wu massed three hundred chariots and swung around to take Anyang from the rear. A probably contemporary poem makes it sound like these Zhou chariots were decisive:

The war chariots

gleamed,

The team of white-bellies

*

was tough …

Ah, that King Wu

Swiftly fell upon Great Shang,

Who before daybreak begged for a truce.

Di Xin committed suicide. Wu won over some Shang leaders, executed others, and left Di Xin’s son as a vassal king. Wu’s political arrangements soon ran into trouble, as we will see in

Chapter 5

, but by then the gap in social development between East and West had narrowed sharply. The West had got a two-thousand-year head start over the East in agriculture, villages, cities, and states, but across the third and second millennia

BCE

the West’s lead steadily shrank to just a thousand years.

As long ago as the 1920s most Western archaeologists thought they knew why China had started catching up: it was because the Chinese had copied almost everything—agriculture, pottery, building, metallurgy, chariots—from the West. Sir Grafton Elliot Smith, a British anatomist in Cairo, was so enthusiastic that he even managed to give Egypt envy a bad name. Wherever in the world he looked and whatever he looked at—pyramids, tattooing, stories about dwarfs and giants—Elliot Smith saw the copying of Egyptian archetypes, because, he convinced himself, Egyptian “

Children of the Sun

” had carried a “heliolithic” (“sun and stone”) culture around the world. When we get right down to it, Elliot Smith concluded, we are all Egyptians.

Some of this seemed fairly nutty even at the time, and since the 1950s archaeology has steadily disproved nearly all Elliot Smith’s claims. Eastern agriculture arose independently; Easterners used pottery thousands of years before Westerners; the East had its own traditions of monumental building; even human sacrifice was an independent Eastern invention. Yet despite all these findings, some important ideas clearly did move from West to East, above all bronzeworking. That

metal, so important at Erlitou, is first seen in China not in the developed Yiluo Valley but in arid, windswept Xinjiang far to the northwest, probably after being brought across the steppes by the Western-looking people whose burials in the Tarim Basin I mentioned earlier. Chariots, as we have seen, probably entered the same way, just five hundred years after they had reached the Western core from the steppes.

But while West-to-East diffusion probably explains some of China’s catch-up, the most important factor by far was not Eastern copying but the Western collapse. Eastern social development was still a thousand years behind the West’s in 1200

BCE

, but the Western core’s implosion effectively wiped out six centuries’ worth of gains. By 1000

BCE

the East’s development score was only a few hundred years behind the West’s. The great Western collapse of 1200–1000

BCE

began the first turning point in our story.

HORSEMEN OF THE APOCALYPSE

Just why the Western core broke down, though, remains one of history’s greatest mysteries. If I had a cast-iron answer, I would of course have mentioned it by now, but the sad fact is that unless some stroke of luck provides a whole new kind of evidence, we will probably never know.

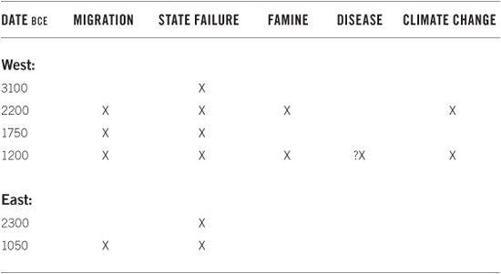

All the same, looking systematically at the disruptions of social development described in this chapter is rather illuminating.

Table 4.1

summarizes what strike me as their most important features.

We know so little about the disruptions that undid the Uruk expansion in the West around 3100

BCE

and Taosi in the East around 2300 that we should probably leave them out of the discussion, but the four cases of upheavals that remain break down into two pairs. The first pair—the Western crisis after 1750

BCE

and the Eastern crisis around 1050—was, we might say, man-made. Chariot warfare shifted the balance of power; ambitious newcomers pushed into the cores; violence, migration, and regime change ensued. The main outcome, in both cases, was a shift in power toward formerly peripheral groups, with development continuing to move upward.

The second pair—the Western crises of 2200–2000 and 1200–1000

BCE

—was quite different, most obviously because nature magnified

human folly. Climate change was largely beyond human control, and was at least partly responsible for the famines in these periods (though if the biblical story of Joseph is any guide, poor planning probably contributed too). This second pair of disruptions was much more severe than the first, and we might draw a tentative conclusion from this: that when the four horsemen of the apocalypse—climate change, famine, state failure, and migration—ride together, and especially when a fifth horseman of disease joins them, disruptions can turn into collapses, sometimes even driving social development down.

Table 4.1. The horsemen of the apocalypse: the documented dimensions of disasters, 3100–1050

BCE

Yet we cannot conclude that the orbital tilts and wobbles behind climate change straightforwardly

caused

collapse. The drought that afflicted the Western core around 2200

BCE

seems to have been harsher than that around 1200, yet the core muddled through between 2200 and 2000 while it fell apart between 1200 and 1000

BCE

. The drought starting around 3800

BCE

may have been worse than either 2200 or 1200, but it had relatively little impact in the East and actually drove social development upward in the West.

This suggests a second possibility: that collapse comes out of the interactions between natural and human forces. I think we can probably be more specific about this: bigger, more complex cores generate bigger, more threatening upheavals, increasing the risk that disruptive

forces such as climate change and migration will set off thoroughgoing collapses. Around 2200

BCE

the Western core was already large, with palaces, godlike kings, and redistributive economies covering the whole area from Egypt to Mesopotamia. When drought and migrations out of the Syrian Desert and Zagros Mountains shook up this region’s internal and external relationships, the results were horrific, but because the twin core areas of Egypt and Mesopotamia were not very tightly linked, each stood or fell independently. By 2100

BCE

Egypt had partly collapsed, but Mesopotamia revived; and when Mesopotamia partly collapsed around 2000

BCE

, Egypt revived.

In 1200

BCE

, by contrast, the core had expanded into Anatolia and Greece, reached the oases of central Asia, and even touched Sudan. Migrations apparently began on the unstable new Mediterranean frontier, but in the twelfth century

BCE

peoples were on the move everywhere from Iran to Italy. The snowball they created was much, much bigger than anything previously seen, and rolled across a more interconnected core that had more to go wrong. Raiders burned the crops at Ugarit because the king had sent his army to help the Hittites; disasters in one place compounded those in another in ways that had not happened a thousand years earlier. When one kingdom fell, it affected others. Chaos extended across the eleventh century

BCE

and finally dragged everyone down.

The paradox of social development—the tendency for development to generate the very forces that undermine it—means that bigger cores create bigger problems for themselves. It is all too familiar in our own age. The rise of international finance in the nineteenth century (

CE

) tied together capitalist nations in Europe and America and helped push social development upward faster than ever before, but this also made it possible for an American stock market bubble in 1929 to drag all these countries down; and the staggering increase in financial sophistication that helped push social development up in the last fifty years also made it possible for a new American bubble in 2008 to shake virtually the whole world to its foundations.

This is an alarming conclusion, but we can also derive a third, more optimistic, point from the troubled history of these early states. Bigger, more complex cores generate bigger, more threatening disruptions but also offer more, and more sophisticated, ways to respond to them. The

world’s financial leaders pounced on the crash of 2008 in ways that had been unimaginable in 1929, and as I write (in early 2010), seem to have averted a meltdown like that of the 1930s.

As social development moves upward it sets off a race between ever more threatening disruptions and ever more sophisticated defenses. Sometimes, as happened in the West around 2200 and 1200

BCE

, the challenges overwhelm the responses available. Whether because leaders make mistakes, institutions fail, or the organization and technology are just not there, problems spiral out of control, disruption turns into collapse, and social development goes backward.

Before the collapse of 1200–1000

BCE

, Western social development had been running well ahead of Eastern for thirteen thousand years. There was every reason to think the West’s lead was permanent. After the collapse, the West’s lead was wafer-thin; another such setback could wipe it out altogether. The paradox of social development, played out so brutally and so often between 5000 and 1000

BCE

, showed that nothing lasts forever. No simple long-term lock-in theory can tell us why the West rules.

5

NECK AND NECK

THE ADVANTAGES OF DULLNESS

Figure 5.1

may be the dullest diagram ever. Unlike

Figure 4.2

, it has no great divergences, disruptions, or convergences—just two lines drifting along in parallel for nearly a thousand years.

Yet while

Figure 5.1

may be plain vanilla, the things that

don’t

happen in it are crucial for our story. We saw in

Chapter 4

that when the Western core collapsed around 1200

BCE

, its lead in social development shrank sharply. It took Western development five centuries to claw its way back up to twenty-four points, where it had stood around 1300

BCE

; if it had collapsed again when it hit this level, that would have wiped out the East-West gap altogether. If, on the other hand, Eastern development had collapsed when it reached twenty-four points, that would have restored the West’s pre-1200

BCE

lead. In reality, as

Figure 5.1

shows, neither of these things happened. Eastern and Western social development kept rising in parallel, in a neck-and-neck race. The mid first millennium

BCE

was one of history’s turning points because history failed to turn.

But what

does

happen in

Figure 5.1

matters too. Social development almost doubled in both East and West between 1000 and 100

BCE

. Western development passed thirty-five points; it was higher when

Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon than it would be when Columbus crossed the Atlantic.