Why the West Rules--For Now (56 page)

Read Why the West Rules--For Now Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Tags: #History, #Modern, #General, #Business & Economics, #International, #Economics

On the other hand, new dowry patterns and liberal (compared to Confucian ideas, anyway) Buddhist attitudes toward female abilities

gave the wealthiest women scope to ignore grandfather’s instructions. Take Wu Zetian, who, after one kind of service as a Buddhist nun, took up another (aged thirteen) as a concubine in the emperor’s harem, before marrying his son as a junior wife. Wu ran rings around her dizzy, easygoing husband, ruling from behind the bamboo curtain, as the saying went. And when her husband conveniently died in 683, Wu allegedly poisoned the obvious heir, then deposed two of her own sons (one after six weeks, the other after six years). In 690 she pulled back the bamboo curtain to become the only woman who ever sat on China’s throne in her own right.

In some ways Wu was the ultimate protofeminist. She founded a research institute to write a

Collection of Biographies of Famous Women

and scandalized conservatives by leading a female procession to Mount Tai for China’s most sacred ritual, the Sacrifice to Heaven. Sisterhood had its limits, though—when her husband’s senior wife and favorite concubine became a threat while Wu was maneuvering her way to the top, she (again, allegedly) suffocated her own baby, framed her rivals, then punished them by chopping off their arms and legs and drowning them in a vat of wine.

Wu’s Buddhism was as contradictory as her protofeminism. She was certainly devout, at one point outlawing butchers’ shops and at another personally going beyond Chang’an’s city limits to meet a monk returning from collecting sacred texts in India, yet she flagrantly exploited religion for political ends. In 685 her lover—another monk—“found” a text called the Great Cloud Sutra, predicting the rise of a woman of such merit that she would become the universal ruler. Wu took the title Maitreya (Future Buddha) the Peerless, and legend holds that the face of the beautiful Maitreya Buddha statue at Longmen reflects Wu’s (

Figure 7.3

).

Wu had an equally complicated relationship with the civil service. She promoted entrance examinations over family connections, yet the Confucian gentleman scholars whose dominance this guaranteed hated their female ruler with a passion, and she returned the sentiment. Wu purged the scholars, who retaliated by writing official histories making her the archetype of what went wrong when women were on top.

But not even they could conceal the splendor of her reign. She commanded a million-strong army and the resources to send it deep

into the steppes. More like the Roman army than the Han, it recruited largely within the empire and drew officers from the gentry. It could intimidate internal rivals but elaborate precautions kept its commanders loyal. Any officer who moved even ten men without permission faced a year in prison; any who moved a regiment risked strangulation.

Figure 7.3. The face of Wu Zetian? Legend has it that this monumental statue of the Future Buddha, carved at Longmen around 700, was modeled on the only woman to rule China in her own name.

The army took Chinese rule farther into northeast, Southeast, and central Asia than ever before, even intervening in northern India in 648, and China’s “soft” power reached further still. In the second through fifth centuries, India had eclipsed China as a cultural center of gravity, its missionaries and traders spreading Buddhism far and wide, and the elites of newly forming Southeast Asian states adopted Indian dress and scripts as well as religion. By the seventh century, though, China’s

influence was also being felt. A distinctive Indochinese civilization developed in Southeast Asia, Chinese schools of Buddhism shaped thought back in India, and the ruling classes in Korea’s and Japan’s emerging states learned their Buddhism entirely from China. They aped Chinese dress, town planning, law codes, and writing, and buttressed their power by claiming both approval and descent from China’s rulers.

Part of Chinese culture’s appeal was its own openness to foreign ideas and ability to blend them into something new. Many of the most powerful people in Wu’s world could trace their ancestry back to steppe nomads who had migrated into China, and they maintained their ties to the steppe highway linking East and West. Inner Asian dancers and lutes were all the rage in Chang’an, where fashionistas wore Persian dresses with tight-laced bodices, pleated skirts, and yards of veils. True trendsetters would use only East African “devil slaves” as doormen; “

If they do not die

,” one owner coldly observed, “one can keep them, and after being kept a long time they begin to understand the language of human beings, though they themselves cannot speak it.”

The scions of China’s great houses broke their bones playing polo, the nomads’ game of choice; everyone learned to sit, central-Asian style, on chairs rather than mats; and stylish ladies dallied at the shrines of exotic religions such as Zoroastrianism and Christianity, carried east by the central Asian, Iranian, Indian, and Arab merchants who flocked to Chinese cities. In 2007 a DNA study suggested that one Yu Hong, buried at Taiyuan in northern China in 592, was actually European (though whether he himself migrated all the way from the western to the eastern end of the steppes or whether his ancestors had made the move more slowly remains unclear).

Wu’s world was the product of China’s unification in 589, which imposed a powerful state on the south and opened a vast realm to southern economic development. That explains why Eastern social development rose so rapidly; but it is only half the explanation for why the Eastern and Western scores crossed around 541. For a full answer we also need to know why Western social development kept falling.

THE LAST OF THEIR BREEDS

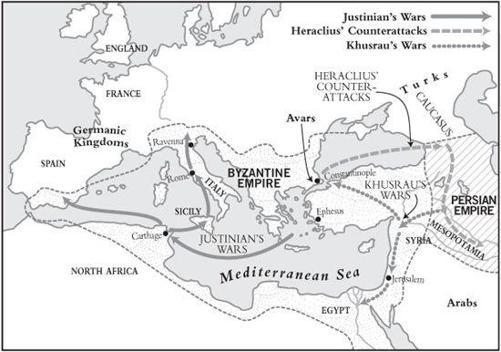

On the face of it, Western recovery seemed at least as likely as Eastern in the sixth century. In each core a huge ancient empire had broken down, leaving a smaller empire that claimed legitimate rule over the whole region and a cluster of “barbarian” kingdoms that ignored such claims (

Figure 7.4

). After the calamities of the fifth century, Byzantium had shored up its frontiers and enjoyed relative calm, and by 527, when a new emperor named Justinian ascended the throne, all signs were positive.

Historians often call Justinian the last of the Romans. He governed with furious energy, overhauling administration, strengthening taxes, and rebuilding Constantinople (the magnificent church Hagia Sophia is part of his legacy). He worked like a demon. Some critics insisted that he really

was

a demon—like some Hollywood vampire, they claimed, he never ate, drank, or slept, although he did have voracious sexual appetites. Some even said they had seen his head separate from his body and fly around on its own as he prowled the corridors at night.

Figure 7.4. The last of their breeds? First Justinian of Byzantium (533–565) and then Khusrau of Persia (603–627) attempt to reunite the Western core; Heraclius of Byzantium strikes back against Khusrau (624–628).

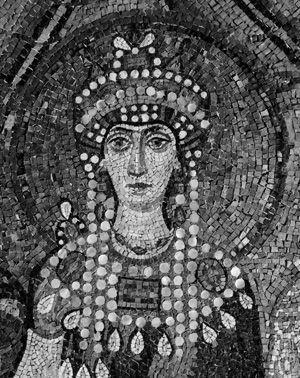

What chiefly drove Justinian, according to gossip, was his wife, Theodora (

Figure 7.5

), who got even worse press than Wu Zetian. Theodora had been an actress (in antiquity, often a euphemism for prostitute) before marrying Justinian. Rumor had it that her sex drive outdid even his; that she once slept with all the guests at a dinner party and then, when they were exhausted, worked through their thirty servants; and that she used to complain because God had given her only three orifices. Be that as it may, she was very much an empress. When aristocrats opposing Justinian’s taxes tried to use rioting sports fans to overthrow him in 532, for instance, it was Theodora who stopped him from fleeing. “

Everyone born

must die,” she pointed out, “but I would not live to see the day when men do not call me ‘Your Majesty.’ If you seek safety, husband, that is easy … but I prefer the old saying—purple [the color of kings] makes the best shroud.” Justinian pulled himself together, sent in the army, and never looked back.

Figure 7.5. Worse (or better, depending on your perspective) than Wu? Empress Theodora, as represented on a mosaic at Ravenna in Italy, completed in 547

The very next year Justinian dispatched his general Belisarius to wrest North Africa from the Vandals. Sixty-five years earlier fireships had sent Byzantium’s hopes of retaking Carthage up in smoke, but now it was the Vandals’ turn to collapse. Belisarius swept through North Africa, then crossed to Sicily. There the Goths fell apart too, and Justinian’s general celebrated Christmas 536 in Rome. All was going perfectly. Yet by the time Justinian died in 565 the reconquest had stalled, the empire was bankrupt, and Western social development had fallen below the East’s. What went wrong?

According to Belisarius’ secretary Procopius, who left an account called

The Secret History

, it was all the fault of women. Procopius provided a convoluted conspiracy theory worthy of Empress Wu’s Confucian civil servants. Belisarius’ wife, Antonina, Procopius said, was Empress Theodora’s best friend and partner in sexual high jinks. To distract Justinian from the all-too-true gossip about Antonina (and herself), Theodora undermined Belisarius in Justinian’s eyes. Convinced that Belisarius was plotting against him, Justinian recalled him—only for the Byzantine army, lost without its general, to be defeated. Justinian sent Belisarius back to save the day; then, paranoid once more, reran the whole foolish cycle (several times).

How much truth Procopius’ story holds is anyone’s guess, but the real explanation for the reconquest’s failure seems to be that despite the similarities between the Eastern and Western cores in the sixth century, the differences mattered more. Strategically, Justinian’s position was almost the opposite of Wendi’s when he united China. In China, all the northern “barbarian” kingdoms formed a single unit by 577, which Wendi used to overcome the rich but weak south. Justinian, by contrast, was trying to conquer a multitude of mostly poor but strong “barbarian” kingdoms from the rich Byzantine Empire. Reuniting the core in a single campaign, like Wendi’s in 589, was impossible.

Justinian also had to deal with Persia. For a century a string of wars with the Huns, conflicts over taxes, and religious upheavals had kept Persia militarily quiet, but the prospect of the Roman Empire rising

from the ashes demanded action. In 540 a Persian army broke through Byzantium’s weakened defenses and plundered Syria, forcing Justinian to fight on two fronts (which probably had more to do with Belisarius’ recall from Italy than any of Antonina’s intrigues).

As if this were not enough, an unpleasant new sickness was reported in Egypt in 541. People felt feverish and their groins and armpits swelled. Within a day or so the swellings blackened and sufferers fell into comas and delirium. After another day or two most victims died, raving with pain.

It was the bubonic plague. The sickness reached Constantinople a year later, probably killing a hundred thousand people. The risk of death was so high, Bishop John of Ephesus claimed, that “

nobody would go

out of doors without a tag bearing his name hung round his neck.”