Why the West Rules--For Now (70 page)

Read Why the West Rules--For Now Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Tags: #History, #Modern, #General, #Business & Economics, #International, #Economics

Whatever his fate, Pires learned the hard way that despite their guns, here at the real center of the world Europeans still counted for little. They had destroyed the Aztecs and shot their way into the markets of the Indian Ocean, but it took more than that to impress the gatekeepers of All Under Heaven. Eastern social development remained far ahead of Western, and despite Europe’s Renaissance, sailors, and guns, in 1521 there was still little to suggest that the West would narrow the gap significantly. Three more centuries would pass before it became clear just what a difference it made that Cortés, not Zheng, had burned Tenochtitlán.

9

THE WEST CATCHES UP

THE RISING TIDE

“

A rising tide

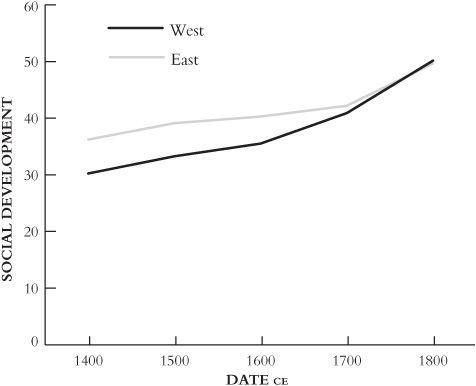

lifts all the boats,” said President John F. Kennedy. Never was this truer than between 1500 and 1800, when for three centuries Eastern and Western social development both floated upward (

Figure 9.1

). By 1700 both were pushing the hard ceiling around forty-three points; by 1750 both had passed it.

Kennedy spoke his famous line in Heber Springs, Arkansas, in a speech to celebrate a new dam. The project struck his critics as the worst kind of pork barrel spending: sure, they observed, the proverbial rising tide lifts all the boats, but it lifts some faster than others. That, too, was never truer than between 1500 and 1800. Eastern social development rose by a quarter, but the West’s rose twice as fast. In 1773 (or, allowing a reasonable margin of error, somewhere between 1750 and 1800) Western development overtook the East’s, ending the twelve-hundred-year Eastern age.

Historians argue passionately over why the global tide rose so much after 1500 and why the Western boat proved particularly buoyant. In this chapter I suggest that the two questions are linked and that once we set them into their proper context, of the long-term saga of social development, the answers are no longer so mysterious.

Figure 9.1. Some boats float better than others: in the eighteenth century the rising tide of social development pushed East and West through the ceiling that had always constrained organic economies, but pushed the West harder, further, and faster. In 1773, according to the index, the West regained the lead.

MICE IN A BARN

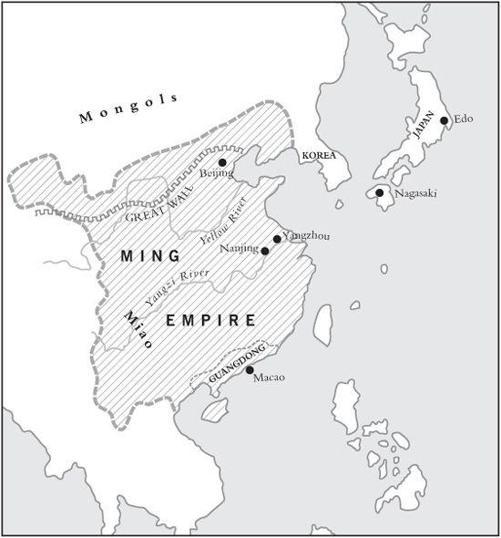

It took a while to get over Tomé Pires. Not until 1557 did Chinese officials start turning a blind eye to the Portuguese traders who were settling at Macao (

Figure 9.2

), and although by 1570 other Portuguese traders had set up shop as far around the coasts of Asia as Nagasaki in Japan, their numbers remained pitifully small. To most Westerners, the lands of the Orient remained merely magical names; to most Easterners, Portugal was not even that.

The main impact these European adventurers did have on ordinary Easterners’ lives in the sixteenth century was through the extraordinary plants—corn, potatoes, sweet potatoes, peanuts—they brought from the New World. These grew where nothing else would, survived wretched weather, and fattened farmers and their animals wonderfully. Across the sixteenth century millions of acres of them were planted, from Ireland to the Yellow River.

Figure 9.2. A crowded world: the East in an age of rising tides, 1500–1700

They came, perhaps, in the nick of time. The sixteenth century was a golden age for Eastern and Western culture. In the 1590s (admittedly a particularly good decade) Londoners could watch new dramas such as Shakespeare’s

Henry V

,

Julius Caesar

, and

Hamlet

or read inexpensive religious tracts such as John Foxe’s gory

Book of Martyrs

, churned out in their thousands by the new printing presses and crammed with woodcuts of true believers at the stake. At the other end of Eurasia, Beijingers could catch Tang Xianzu’s twenty-hour-long

Peony Pavilion

, which remains China’s most-watched traditional opera, or read

The Journey to the West

(the hundred-chapter tale of Monkey, Pig, and a Shrek-like ogre named Friar Sand, who followed a seventh-century

monk to India to find Buddhist sutras, along the way rescuing him from countless cliff-hangers).

But behind the glittering façade all was not well. The Black Death had killed a third or more of the people in the Western and Eastern cores and for about a century after 1350 recurring outbreaks kept population low. Between 1450 and 1600, however, the number of hungry mouths in each region roughly doubled. “

Population has grown

so much that it is entirely without parallel in history,” one Chinese scholar recorded in 1608. In faraway France observers agreed; people were breeding “

like mice

in a barn,” as a proverb put it.

Fear has ever been an engine of social development. More children meant more subdivided fields or more heirs left out in the cold, and always meant more trouble. Farmers weeded and manured more often, dammed streams, and dug wells, or wove and tried to sell more garments. Some settled on marginal land, squeezing a meager living from hillsides, stones, and sand that their parents would never have bothered with. Others abandoned the densely settled cores for wild, underpopulated frontiers. Yet even when they planted the New World wonder crops, there never seemed to be enough to go around.

The fifteenth century, when labor had been scarce and land abundant, increasingly became just a fuzzy memory: happy days, beef and ale, pork and wine. Back then, said the prefect of a county near Nanjing in 1609, everything had been better: “

Every family

was self-sufficient with a house to live in, land to cultivate, hills from which to cut firewood, gardens in which to grow vegetables.” Now, though, “nine out of ten are impoverished … Avarice is without limit, flesh injures bone … Alas!” A German traveler around 1550 was blunter: “

In the past

they ate differently at the peasant’s house. Then, there was meat and food in profusion.” Today, though, “everything is truly changed … the food of the most comfortably off peasants is almost worse than that of day laborers and valets in the old days.”

In the English fairy tale of Dick Whittington (which, like many such stories, goes back to the sixteenth century), a poor boy and his cat drift from the countryside to London and make good, but in the real world many of the hungry millions that fled to cities merely jumped from the frying pan into the fire.

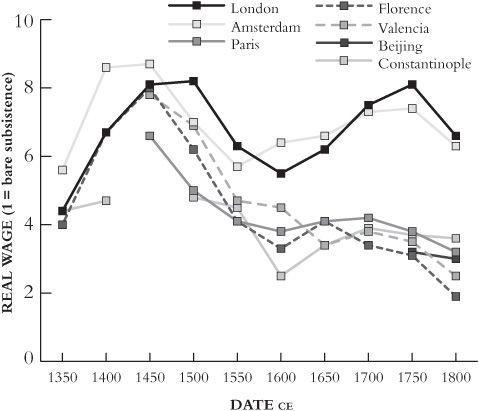

Figure 9.3

shows how urban real wages (that is, consumers’ ability to buy basic goods, corrected to account for inflation) changed after 1350. The graph rests on years of

painstaking detective work by economic historians, deciphering crumbling records, recorded in a regular Babel of tongues and measured in an even greater confusion of units. Not until the fourteenth century do European archives begin providing data good enough to calculate incomes this precisely, while in China we have to wait until after 1700. But despite the gaps in the data and the mass of crisscrossing lines, the Western trend, at least, is clear. Basically, wages roughly doubled everywhere we have evidence in the century after the Black Death, then, as population recovered, mostly fell back to pre–Black Death levels. The Florentines who hauled blocks and raised the soaring dome of Brunelleschi’s cathedral in the 1420s feasted on meat, cheese, and

olives; those who dragged Michelangelo’s David into place in 1504 made do with bread. A century later their great-grandchildren were happy to get even that.

Figure 9.3. For richer, for poorer: the real wages of unskilled urban workers in six Western cities plus Beijing, 1350–1800. Every city and every industry had its own story, but almost everywhere we can measure it, after roughly doubling between 1350 and 1450 workers’ purchasing power fell back to pre-1350 levels by 1550 or 1600. For reasons that will become clear later in the chapter, after 1600 cities in Europe’s northwest increasingly pulled away from the rest. (Data begin at Paris and Valencia only around 1450 and at Beijing around 1750, and—not surprisingly—there is a gap in the figures from Constantinople around 1453, when the Ottomans sacked the city.) Data from Allen 2006, Figure 2.

By then hunger stalked Eurasia from end to end. A disappointing harvest, an ill-advised decision, or just bad luck could drive poor families to scavenging (in China for chaff and bean pods, tree bark and weeds, in Europe for cabbage stumps, weeds, and grass). A run of disasters could push thousands onto the roads in search of food and the weakest into starvation. It is probably no coincidence that in the original versions of Europe’s oldest folktales (like

Dick Whittington

), peasant storytellers dreamed not of golden eggs and magic beanstalks but of actual eggs and beans. All they asked from fairy godmothers was a full stomach.

In both East and West the middling sorts steadily hardened their hearts against tramps and beggars, herding them into poorhouses and prisons, shipping them to frontiers, or selling them into slavery. Callous this certainly was, but those who were slightly better off apparently felt they had troubles enough of their own without worrying about others. As one gentleman observed in the Yangzi Delta in 1545, when times were tough “

the stricken

[that is, poorest] were excused from paying taxes,” but “the prosperous were so pressed that they also became impoverished.” Downward social mobility stared the children of once-respectable folk in the face.

The sons of the gentry found new ways to compete for wealth and power in this harder world, horrifying conservatives with their scorn for tradition. “

Rare styles

of clothing and hats are gradually being worn,” a Chinese official noted with alarm; “and there are even those who become merchants!” Worse still, one of his colleagues wrote, even formerly respectable families

are mad for

wealth and eminence … Taking delight in filing accusations, they use their power to press their cases so hard that you can’t distinguish between the crooked and the straight. Favoring lavishness and fine style, they drag their white silk garments as they roam about such that you can’t tell who is honored and who base.