Woman Who Could Not Forget (61 page)

Read Woman Who Could Not Forget Online

Authors: Richard Rhodes

It was

The Rape of Nanking.

And it was on that day that I first saw those two beautiful words . . . Iris Chang.

Somehow I got up the courage to write a letter to your mother.

She responded with a picture postcard encouraging me.

The picture on the postcard was a photo of her.

I hung the postcard photo of Iris on the wall of my study.

Every day, as I wrote through my fears, I said to myself, “If she can do it, I can do it.”

Flags of Our Fathers

became a

New York Times

#1 best seller. Twenty-seven publishers had said “no.” Your mother had said “Do it.”

Then I wanted to write a second book, but I couldn’t find a story.

I turned once again to your mother.

She e-mailed me a suggestion that I contact a guy named Bill in Iowa who had some “interesting information.”

I phoned Bill, who then gave me the story that became my second book,

Flyboys.

This book, a gift from your mother, became a #2 best seller.

The opening line of

Flyboys

begins with the words, “The e-mail was from Iris Chang. . . .”

At the back of the book is the Acknowledgement—my opportunity to thank those who made

Flyboys

possible.

The Acknowledgment in

Flyboys

begins with those beautiful two words . . .

“Iris Chang.”

Christopher, since writing these books, I have addressed hundreds of audiences around the world.

And I have learned that I am just one of thousands who owes thanks to your mother.

In my quest to find out about my father, I learned that in the brutal battle of Iwo Jima, my dad—a medical officer—held over two hundred screaming young boys in his arms as they died.

And in your quest to find out about your mother, you will learn that she held hundreds . . . thousands . . . no, hundreds of thousands—of tortured dead and screaming victims in her mind’s eye.

Iris Chang touched millions and will be remembered on all continents in countless ways.

Here is just one of them.

Four years ago, I established the

James Bradley Peace Foundation

.

The foundation sends American high-school students to China and Japan for one year, to live and study.

The goal of the foundation is to create understanding across cultures so that some day, arms like my father’s won’t hold the dying . . . and minds’ eyes like your mother’s won’t have to hold war’s dead.

Two days ago, our board met and decided that from now on, the American students we send to China will do so as recipients of our foundation’s new

Iris Chang Memorial Scholarship.

Christopher, when you are older, I invite you to come and sit on our board. Come help us choose more students worthy of the

Iris Chang Memorial Scholarship.

By then, you’ll be able to meet the many students who will have studied in China in your mother’s name.

They will tell you what I already know:

About how when they entered China, they saw the beautiful words “Iris Chang” in the airport bookstores . . . city bookstores . . . and libraries across the land.

How Chinese students study your mother’s words to learn their country’s history.

And how her photo graces museum walls there, motivating others to search for the truth.

Christopher, as you grow older, my hope is that you can experience three things that I have.

Someday you will learn that of which your mother could not speak.

I hope it will help you understand your mother’s legacy, as I have come to understand my father’s.

I hope you will someday work sitting under a photo of your mother and feel the warm power of her special inspiration felt by so many others and me.

And later—when you make that difficult but rewarding inner journey to discover your unique mission in the universe—when you find your personal truth—I hope you will acknowledge the example of your valiant mother, who once fearlessly told truth to the world.

Perhaps you will write an acknowledgement to her, a thank-you like I once did.

A thank-you that begins with two bright and hopeful words.

Those two beautiful words . . .

. . . Iris Chang.

by Steven Clemons

http://www.thewashingtonnote.com/archives/2004/11/requiem_for_iri/index.php

I HAVE JUST BEEN GUT-PUNCHED BY THE NEWS that a dear friend and intellectual soul mate over the last several years, Iris Chang, was found dead in her car near Santa Clara, California.

Iris’s book,

The Rape of Nanking: The Forgotten Holocaust of World War II,

had immeasurable impact on a collective historical amnesia problem not only in Japan, but also in the United States and around the world. This brilliant and beautiful writer and thinker was, to me, a modern Joan of Arc riding into the nastiest of battles calling for honest and fair reconciliation with the past.

We met via e-mail years ago. She joined a quest I was on some years ago to try and get people to look seriously at the contemporary legal consequences of back room deal-making by John Foster Dulles on the eve of signing the San Francisco Peace Treaty, formally ending Allied Occupation of Japan on September 8, 1951. I wrote a

New York Times

piece on this subject, which appeared on 4 September 2001.

Whereas I thought I had found an interesting historical tidbit that had been neglected by historians and lawyers, Iris Chang knew that I had just wandered unsuspecting into a raging battle between Chinese and Japanese warriors over memory and the historical record. She called me, and we had a two-hour phone conversation where she helped prepare me for the onslaught of criticism that would fly my way from those who wanted to preclude any discussion of Japan’s wartime responsibilities.

She followed up with her own

New York Times

articles on the debate about Japan, war memory, and what I called—America’s complicity in Japan’s historical amnesia. Unfortunately, her articles are not available on the Internet.

We met several times in person, once after a talk I gave at De Anza College in Cupertino, California, where she sat anonymously in the back of a room of 500-600 people interested in Japan’s war memory debate. This subject is one she owned—and was one that I had just stumbled into—but her brilliance and authority on this subject was tempered by intimidating modesty. She never let anyone know that she was there at De Anza.

We also shared a platform together at a conference organized in April 2002 by the University of San Francico Center for the Pacific Rim.

It would be irresponsible for me to suggest anything more than the authorities are suggesting about her death, but I would only add that I find it distressing and worrisome that two brilliant change-agents, Iris Chang and the late film-maker Juzo Itami, who made us see our worlds differently than we otherwise would—each supposedly committed suicide, after bouts of depression. I have never bought the story about Juzo Itami, whom I also knew and who was at war in his films with Japan’s national right wing crowd and yakuza.

I have no choice but to accept what has been reported about Iris’s death—but all I can say, and I can barely express anything sensible about this tragedy, is that the world has lost much in her passing.

Iris Chang wrestled with the tensions between conviction, faith, and communal lies. She was attacked from so many corners for her important work that she tried to untangle why truth was so frequently strangled by conviction, faith, and delusion.

We once discussed at length this passage from Friedrich Nietzsche’s “The Anti-Christ.” I don’t believe that Iris was a Nietzsche acolyte, but what follows below captures much of what we were both struggling with at the time:

One step further in the psychology of conviction, of “faith.” It is now a good while since I first proposed for consideration the question whether convictions are not even more dangerous enemies to truth than lies. (“Human, All-Too-Human,” I, aphorism 483.)

This time I desire to put the question definitely: is there any actual difference between a lie and a conviction?—All the world believes that there is; but what is not believed by all the world!—Every conviction has its history, its primitive forms, its stage of tentativeness and error: it becomes a conviction only after having been, for a long time, not one, and then, for an even longer time, hardly one.

What if falsehood be also one of these embryonic forms of conviction?—Sometimes all that is needed is a change in persons: what was a lie in the father becomes a conviction in the son.—I call it lying to refuse to see what one sees, or to refuse to see it as it is: whether the lie be uttered before witnesses or not before witnesses is of no consequence.

The most common sort of lie is that by which a man deceives himself: the deception of others is a relatively rare offense.—Now, this will not to see what one sees, this will not to see it as it is, is almost the first requisite for all who belong to a party of whatever sort: the party man becomes inevitably a liar. For example, the German historians are convinced that Rome was synonymous with despotism and that the Germanic peoples brought the spirit of liberty into the world: what is the difference between this conviction and a lie?

Is it to be wondered at that all partisans, including the German historians, instinctively roll the fine phrases of morality upon their tongues—that morality almost owes its very survival to the fact that the party man of every sort has need of it every moment?—“This is our conviction: we publish it to the whole world; we live and die for it—let us respect all who have convictions!”—I have actually heard such sentiments from the mouths of anti-Semites. On the contrary, gentlemen!

An anti-Semite surely does not become more respectable because he lies on principle. . . . The priests, who have more finesse in such matters, and who well understand the objection that lies against the notion of a conviction, which is to say, of a falsehood that becomes a matter of principle because it serves a purpose, have borrowed from the Jews the shrewd device of sneaking in the concepts, “God,” “the will of God” and “the revelation of God” at this place.

I am too sad to write more about her now.

Arafat’s passing has been grabbed by many as an opportunity to move the sorry state of Israeli-Palestinian conflict in a new direction.

Perhaps those in Japan who reviled Iris Chang’s important work can step down from their strident defense of a white-washed history and find a course that leads to a more introspective and self-aware nationalism than is the case today.

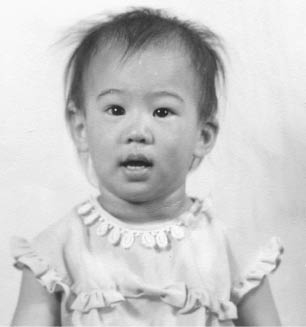

Iris as a one-year-old in Princeton, N. J.

Iris at 15 months with Ying-Ying and Shau-Jin during a trip to Vienna, Austria.

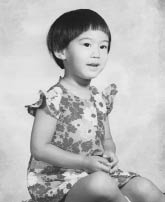

As a three-year-old in Urbana, Illinois.