Would You Kill the Fat Man (13 page)

Read Would You Kill the Fat Man Online

Authors: David Edmonds

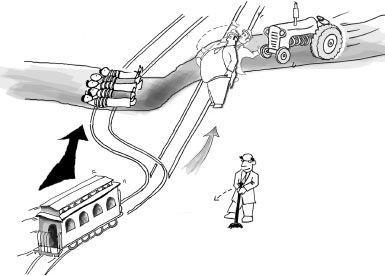

Figure 8

.

Tractor Man.

The runaway trolley is heading toward five innocents. The trolley is not the only thing they’re threatened by. They are also about to be flattened by another, independent, threat. Rampaging in their direction is an out-of-control tractor. To redirect the trolley would be pointless if the five were in any case to be hit by the tractor. But if you turn the trolley away from them, it will gently hit and push, without hurting, another person into the path of the tractor. His being hit by the tractor would stop that vehicle but also kill him. Should you redirect the trolley?

But do you have a strong intuition about what should be done? No? Professor Kamm does. She is sure that it would be wrong to turn the trolley.

Or, instead, take Tumble Case.

This time you can’t redirect the trolley but you can move the five. Unfortunately, the five will tumble down a mountain and their body weight will kill an innocent person below. Is it permissible to move the five? You’re not sure? Professor Kamm says that it is. A few pages farther on there’s the Trolley Tool Case. The trolley is heading toward a useful tool—one that could save many lives. You can redirect the trolley to kill one person. Should you do this? Confused? The answer (her answer) is that you should not.

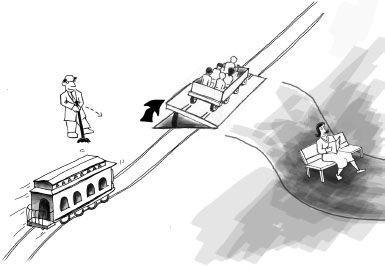

Figure 9

.

The Tumble Case.

The runaway trolley is heading toward five people. You cannot redirect the trolley, but you can move the five. But if you did that, the five would tumble down a mountain and, although they themselves would be unharmed, their body weight would kill an innocent person below. Should you move the five?

But why should we take Kamm’s word for it? Does a professor of philosophy, who has been wandering for decades down

the highways and byways of trolleyology, have especially sensitive moral antennae? Well, perhaps. After all, we expect a wine connoisseur to be superior to ordinary topers in identifying and grading qualities in a wine. We expect something similar of an art buff who can look at a painting and be in a better position than the rest of us to assess its merits.

3

Nonetheless, many of Kamm’s tortuous cases even divide trolleyologists—so an appeal to expertise gets us only so far. That’s not true of Spur and Fat Man, of course, where intuitions are more robust among both philosophers and lay people alike. But the indictment against trolleyology is that all its puzzles are improbable and, therefore, all of them are useless. According to Mary Midgely, even her old friend Philippa Foot would have been dismayed by the burgeoning sub-genre that she spawned: “this trolley-problem industry is just one more depressing example of academic philosophers’ obsession with concentrating on selected, artificial examples so as to dodge the stress of looking at real issues.”

4

In the real world, we don’t have T-junction ethics. In the real world we are not constrained by having just two options, X and Y: we have a multitude of options, and our choices are entangled in complex duties and obligations and motives. In the real world, crucially, there would be no certainty. If I pushed the fat man I could be tried for murder. Perhaps I would be concerned about a CCTV camera capturing my every move. I couldn’t be sure that I’d be physically strong enough to shove the fat man over the bridge (if I tried to push him would there not be a danger that he’d retaliate and throw me over instead?). I couldn’t be sure that the fat man’s bulk would stop the trolley. I couldn’t be sure that without my intervention the trolley would trundle onward and flatten the five.

They might manage to cut their ropes and escape. The driver might regain control of the trolley. And could I not find another bulky object that would be just as effective as the fat man’s body in stopping the trolley?

Trolleys in the Real World

Confronted with the charge of artificiality, the best strategy for trolleyology is to embrace it. The thought experiments are deliberately contrived, yet most of them are not so wildly out of the world as to be entirely unrecognizable from actual cases.

There’s a joke that lampoons moral philosophy. Question. How many moral philosophers does it take to change a light-bulb? Answer. Eight. One to change it and seven to hold everything else equal. But it’s precisely because the trolley scenarios are so carefully engineered that they are of use. Real life is full of white noise, ethical hiss. The complexity of real life makes it difficult to identify pertinent features of moral reasoning. Trolley cases are designed to extract principles and detect relevant distinctions. They can only do so by blotting out the distracting and distorting sound. A crude analogy can be drawn with the scientific method. In the laboratory, if you want to test for the effect of, say, light, you vary the light while maintaining all other factors constant. Similarly, if you want to determine whether a particular feature is relevant morally, you imagine two cases that are otherwise identical while playing around with this one variable.

But neither are the basic trolley cases so fantastical that they’re entirely detached from reality. Earlier I played a little trick on you, dear reader: Professor R U Joaching, referred to at

the beginning of this chapter, is imaginary. But his trolley case is not. This accident took place in Chicago. The appellate court that heard the case ruled in the woman’s favor. The young man who died, Hiroyuki Johu, was held responsible for her injuries: according to the court he should have foreseen that if hit by a train his body would be flung toward the platform and could hurt waiting passengers.

Of course, such cases are themselves outlandish. The point is, however, that they’re not beyond the bounds of the possible. Recently there was another American case that could have been devised by a lecturer of Philosophy 101. It involved Dr. Hootan Roozrokh, declared innocent in a 2009 court judgment in California. What made his case philosophically interesting was the nature of the charges against him.

They concerned a sick man called Ruben Navarro. Navarro was from a working-class Latino background. He was twenty-five years old—about to be twenty-six. Fifteen years earlier his mother Rosa noticed that his balance had begun to deteriorate: when he played with other kids he fell over more frequently than they did. It was like watching Bambi on ice, she said. He was diagnosed with adrenal leukodystrophy—a progressive genetic disability, rare, but made famous by the Hollywood movie,

Lorenzo’s Oil

. When Rosa herself became disabled, Ruben was put into care. His condition rapidly deteriorated. In January 2006, he was rushed to the Sierra Vista Regional Medical Center after being discovered unconscious, and in cardiac and respiratory arrest. Brain damage had been caused by lack of oxygen. The hospital said he would never recover. Rosa was asked and agreed to allow Ruben’s organs to be used after death.

That was when a young doctor, Hootan Roozrokh, made an appearance. Roozrokh had flown in on behalf of the California

Transplant Donor Network, a laudable organization whose stated mission is to save and improve lives through organ and tissue donation for transplantation. Roozrokh was there to collect Ruben’s organs after Ruben was declared dead, but when Ruben was removed from the respirator the plans went awry. Ruben’s body stubbornly hung on to life. Organs have to be removed within 30 to 60 minutes of the respirator being turned off: beyond that time, they are not fresh enough to survive a transplant operation. But Ruben’s heart was only slowly failing and his brain was continuing to function.

The allegation against Dr. Roozrokh was that he had ordered a nurse to administer unusually high doses of two drugs, morphine and Ativan, to Ruben, with the aim of hastening death. As it happened, it took Ruben several hours more to die, by which time his organs were of no use for transplantation. In finding Dr. Roozrokh not guilty, the court accepted his testimony that he had no intention of speeding up death: he simply wanted to ensure the patient would not suffer after life support was withdrawn.

Nonetheless, the charges bore a resemblance to the fictional hospital visitor who could be killed for his organs, a case cited by Judith Jarvis Thomson, Philippa Foot, and others. And although it was unusual, it raised questions similar to those raised in the trolley literature. Had Ruben been killed quickly, several lives could have been saved. The latest figures suggest that in the United States alone, eighteen people die every day awaiting organ transplants—a fatality figure far higher than the U.S. military death toll in Iraq or Afghanistan. Currently more than 100,000 people are on national waiting lists in the United States for heart, lung, liver, kidney, pancreas, or intestine organ transplants.

But even if the trolleyologist rebuts the charge of artificiality, there’s a more fundamental objection still.

• • •

It’s not just trolley intuitions that are suspect: it’s all intuitions.

That is the obvious conclusion to draw from the research not of a philosopher, but of a psychologist—Daniel Kahneman. Kahneman won the Nobel Prize in economics and, with his colleague Amos Tversky, essentially invented the now thriving sub-discipline of behavioral economics—the investigation of how people make economic decisions in practice.

Pre-Tversky/Kahneman, economists of all persuasions were in the grip of an image of producers and consumers as rational economic actors, who made coherent, logical choices based on their particular preferences. Kahneman gave that picture a battering. He and his colleagues carried out numerous experiments that revealed Homo sapiens to be illogical, confused, and sometimes foolish creatures, driven by impulses of which they were often ignorant.

A famous test involved a scenario about a deadly virus. The U.S. authorities are preparing for an outbreak of a disease. Kahneman called it an “Asian disease”—perhaps this was designed to sound particularly threatening. In any case, if nothing is done about the disease, it will kill six hundred people. There are two alternative courses of action.

• YOU CAN ADOPT PROGRAM A. If you do so, two hundred lives will be saved.

• YOU CAN ADOPT PROGRAM B. If you do so, there is a one-third probability that six hundred people will be saved and a two-thirds probability that no people will be saved.

What do you do? Now imagine that the Asian disease will kill six hundred people, but this time you have the following options.

• YOU CAN ADOPT PROGRAM C. If you do so, four hundred people will die.

• YOU CAN ADOPT PROGRAM D. If you do so, there’s a one-third probability that nobody will die and a two-thirds probability that six hundred people will die.

What do you do? In studies, most people thought A was preferable to B, but that D was preferable to C. And this is odd, since A, although expressed in different terms, is exactly the same outcome as C, while B is identical to D. Clearly how the alternatives were framed had an (irrational) impact on how subjects responded.

The same effect has been observed in trolleyology. Philosopher Peter Unger showed students a variation of the Fat Man (giving them the option to divert a large man on motorized roller skates into the path of a deadly trolley).

5

But some students were first exposed to various interim cases (thus, in one interim case students could stop the trolley by diverting another runaway trolley with two people into its path—killing the two). Students who had seen these interim cases were more likely to sanction the large man’s killing when they were eventually confronted with it.

Doubts have also been raised about Judith Jarvis Thomson’s Loop case. Thomson sets out Loop only after Spur. She insists that a few extra meters of track can make no moral difference—and this has struck many philosophers as a compelling claim. Thomson then reasoned that since it was permissible to turn the trolley in Spur, it was equally permissible to do so in Loop.

But a recent study demonstrated that if Loop is shown

prior

to Spur, subjects tend not to see such a close analogy between the two cases, and are more likely to believe that turning the trolley in Loop

is

wrong.

6