Would You Kill the Fat Man (8 page)

Read Would You Kill the Fat Man Online

Authors: David Edmonds

In the search for a formulation of the principles that should govern how we can and can’t treat people, Kamm offers (and critiques) some bafflingly baroque principles. Layer of complexity is heaped upon layer. There are principles galore. There is the principle of alternate reason, the principle of contextual interaction, the principle of ethical integrity, the principle of instrumental rationality, the principle of irrelevant goods, the principle of irrelevant need, the principle of irrelevant rights, and the principle of Secondary Wrong. And we should not forget the principle of the Independence of Irrelevant Alternatives of Permissible Harm, or the principle of Secondary

Permissibility. The latter two are sufficiently significant to merit their own acronym, the PPH and the PSP.

There’s also a smorgasbord of doctrines. However, among them, one is worth highlighting, because it illustrates the ingenuity of Kamm’s work, the fine and subtle distinctions she draws, and also because this distinction, at least, has powerful intuitive appeal. She calls it the Doctrine of Triple Effect. It has a third distinction in addition to the two that are familiar from the DDE, namely effects that are intended and effects that are foreseen. She explains it through what she calls the Party Case.

Suppose that I want to give a party, so that people have a good time, though I realize that a party would result in a terrible mess: there would be glasses to wash, carpets to vacuum, and wine stains to scrub off. I foresee that if my friends have fun, they will feel indebted to me (not a nice feeling) and so help me clean up. I decide to hold the party but only

because

I foresee that they’ll help me afterward. But I don’t hold the party

in order

to make my friends feel indebted, and thus help me: this is not part of my goal. My reason for holding the party is so guests have fun.

16

Kamm draws the conclusion that I don’t intend that my guests feel indebted. Similarly, says Kamm, there’s a distinction between doing something

because it will cause

the hitting of a bystander, and doing it

intending to cause

the hitting of a bystander.

This pretty distinction can assist in various trolley scenarios.

17

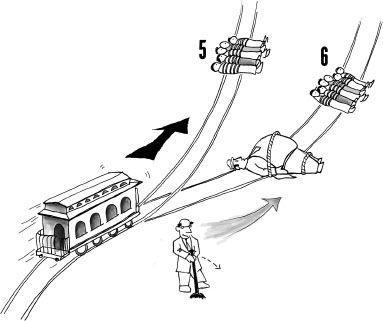

Take the Six Behind One case.

The bystander’s predicament is almost exactly as in Spur, with this difference. Behind the one person on the spur are six people, tied to the track. The one person, if hit, will block the trolley. Since it is permissible to turn the trolley in Spur, a natural intuition is that it must be equally permissible to do so in Six Behind One. But in Spur, the decision to turn the train was justified on the grounds that there was no intention to kill the one. As evidence for this we can imagine how we would feel if this person managed to escape: relief and joy. It would be the best of all possible worlds. The trolley would have been diverted from the five, and no one else would have been killed.

Figure 5

.

Six Behind One.

You are standing on the side of the track. A runaway trolley is hurtling toward you. Ahead are five people, tied to the track. If you do nothing, the five will be run over and killed. Luckily you are next to a signal switch: turning this switch will send the out-of-control trolley down a side track, a spur, just ahead of you. On the spur you see one person tied to the track: changing direction will inevitably result in this person being killed. Behind the one person are six people, also tied to the track. The one person, if hit, will stop the trolley. What should you do? This example is from Otsuka 2008.

But we can’t say the same of Six Behind One. In Six Behind One we want and need the trolley to hit the one. If it doesn’t do so, if the one escapes, the trolley will roll on to kill six. There would be no point turning the trolley unless it hit this one.

So does that mean that if we turn the trolley in Six Behind One, we

intend

to kill the one? And are we thus to deduce that turning the trolley in Six Behind One is morally unacceptable? That doesn’t seem right, not least because hitting the one is not used as a means to saving the five. We didn’t turn the trolley so that we can hit the one.

It’s here that Kamm’s distinction trundles to the rescue. I can say about the Six Behind One case that if I turn the trolley, I do so not

in order to

hit the one, but

because

it will hit the one—and that’s what makes it alright.

As with so many of the scenarios, intuitions about the Six Behind One case will hinge on what the intention is in turning the trolley. Perhaps, then, we should try to clarify what we mean by intention. And we can illustrate the difficulties with a genuine train problem that beset Philippa Foot’s most illustrious relation.

CHAPTER 7

Paving the Road to Hell

What is left over if I subtract the fact that my arm goes up from the fact that I raise my arm?

—Ludwig Wittgenstein

Even a dog knows the difference between being kicked and being stumbled over.

–Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr.

IN MID-1894, GROVER CLEVELAND had personal and public preoccupations on his mind. There was concern about his health and suspicion that he had a malignant tumor. More happily, his family was expanding. His young wife had eight months earlier given birth to a second child, Esther, the only presidential child to this day to be born in the White House itself (Esther would eventually move to England, where her daughter Philippa, would grow up). Meanwhile, seven hundred miles away, in Chicago, the president had a looming and very public trolley problem: an industrial relations crisis that threatened the economic and social stability of the nation.

It had been a boom period for the railroads—Chicago was the railroad capital of the United States, the Pullman Palace

Car Company was about the most prosperous company in the land, and George Pullman, its austere founder, was one of America’s wealthiest citizens. Pullman was an architect of our modern rail system. He built sleeping cars, renowned for their sleek design and opulence. Some of his trains offered exquisite food prepared by revered chefs, and there was attentive service from staff, many of them freed slaves (in the post–Civil War period, Pullman became the largest employer of African Americans). Traveling in a Pullman car was considered the height of luxury.

Working for Pullman was less of a privilege. His rail company had an undeserved reputation for compassionate paternalism. In order to house his thousands of employees, George Pullman came up with the notion of building a model city (one that, today, you can visit and tour), just south of Chicago. The city had all the amenities Pullman deemed necessary—parks, shops, a kindergarten, a library—and he was hailed nationwide as a tremendous benefactor and visionary. He himself said he loved the town like one of his children, and there were a few things to be said in its favor: decent health facilities, for example. But behind the façade, the truth was nastier. Some of the houses were no better than shacks, and often overcrowded: poverty was rife. Pullman ran the place like a despot and not a nickel was donated in charity. The town was expected to pay its way; there were rents and fees for all services (including for use of the library). The one small bar charged inflated prices to deter laborers from frequenting it. The inhabitants were not consulted about what they might want and dissenting views were discouraged: there were no town hall meetings. Leases could be terminated on short notice and tenants might find themselves with nowhere else to go in Pullman, and thus effectively expelled from the tycoon’s utopia.

When, in 1883, the U.S. national economy went into a dramatic downturn, the Pullman Company was itself inevitably and acutely affected. Many workers were laid off. Those that held onto their jobs had their wages cut drastically, while rent for their accommodation, which was deducted automatically from their paychecks, remained unchanged. In May 1884, some workers formed a committee and asked the company to lower the rent. A flat refusal sparked wildcat strikes which gathered momentum and escalated the following month into looting, burning, and mob violence. It represented a furious showdown between capital and labor, between the railway industry and the strongest union in the country, the American Railway Union. President Cleveland called it a “convulsion.”

1

It was the defining episode of his presidency.

When union members began to boycott Pullman trains, rail networks in Illinois and beyond were paralyzed. The industrial unrest eventually enveloped twenty-seven states. In a highly contentious move—against the wishes of the Illinois governor and resented by many Americans—President Cleveland declared the strike a federal crime and sent in thousands of federal troops. (This would receive legal

ex post facto

vindication in the Supreme Court.) The White House believed that the strike endangered interstate commerce as well as the movement of federal mail. Cleveland swore that if it took “every dollar in the Treasury and every soldier in the United States Army to deliver a postal card in Chicago, that postal card shall be delivered.”

2

The intervention of federal troops served only to enrage the strikers, who almost immediately began to overturn and set alight train carriages, even to attack the troops. President Cleveland issued a proclamation in which he explained that those who continued to resist authority would be regarded as

public enemies. The troops had authority “to act with all the moderation and forbearance consistent with the accomplishment of the desired end.”

3

But soldiers would be unable, warned Cleveland, to discriminate between the guilty and those who were present at trouble spots from idle curiosity.

Federal troops were reinforced by far less disciplined state troops and marshals. The violence peaked in early June. By the time the strike was over, at least a dozen lives had been lost in the Chicago area and forty more in clashes with troops in other states. A three-man commission quickly produced a 681-page report to examine who was at fault, and what lessons could be learned.

Proving intent does not require a smoking gun.

—New York Times,

August 25, 1912

Intention is everywhere in the law—not just in criminal law (where it’s needed to separate, for example, murder from manslaughter), but in every variety of the law: in tax law, anti-discrimination law, contract law, and constitutional law.

That troops killed rioters in the Pullman strike is beyond doubt. What’s more difficult to ascertain is their intention. Did they

intend

to kill? How would we determine whether they did or didn’t?

There’s a story about Elizabeth Anscombe repeated by so many people who knew her that it’s almost certainly false. She was in Montreal, at supper time, and she arrived at an expensive restaurant where she was planning to eat. “Sorry Madam,” said the maître d’hôtel, “women are not permitted to wear trousers here.” “Give me a minute,” said Anscombe. And she disappeared to the rest room to reappear a couple of minutes later with exactly the same outfit, minus the trousers.

It seems unlikely that this is what the concierge intended. In everyday conversation we rarely have trouble understanding what is meant by “intending” or “intention.” “Elizabeth Anscombe walked to the shops intending to buy a pint of milk,” would not typically invite the riposte, “what do you mean, intending?” It seems obvious. Question: why did Anscombe go to the shops? Answer: to buy some milk. In fact, intention is a notion wrapped in multilayered complications, which Anscombe herself stripped away in her seminal work

Intention.

4

An intention is not the same as a cause. If someone asks “why did you jump in front of the trolley?” a response might be, “I didn’t jump. I was pushed.” If an act is intentional it makes sense, said Anscombe, not just to ask “why?” but to expect any answer to explain the action’s significance for the person who undertook it.

One of her motives for focusing so much intellectual energy on the concept was her need for a clear understanding of its use in the Doctrine of Double Effect, and in all the ways she applied the DDE, whether in debates over the atomic bomb, abortion, or the use of contraceptives. For example, she believed intention justified distinguishing contraceptive intercourse from intercourse with the rhythm method. The former, but not the latter, she argued, is intended to be nonprocreative, and is immoral. Any sexual act that could never lead to procreation, such as gay sex, was to be condemned. “If contraceptive intercourse is permissible, then what objection could there be after all to mutual masturbation, or copulation

in vase indebito

, sodomy, buggery?”

5