Would You Kill the Fat Man (6 page)

Read Would You Kill the Fat Man Online

Authors: David Edmonds

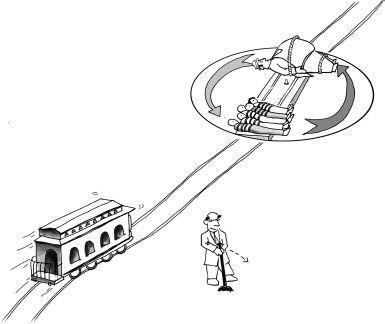

But it was only in the second article that Thomson introduced the stout character who appears in the title of this book.

Foot had originally contrasted the dilemma in Spur with the option of framing an innocent man to save the five hostages and of killing a man so that his organs could save five patients. Thomson made the contrast starker still by introducing another trolley dilemma.

This time you’re on a footbridge overlooking the railway track. You see the trolley hurtling along the track and, ahead of it, five people tied to the rails. Can these five be saved? Again, the moral philosopher has cunningly arranged matters so that they can. There’s a very fat man leaning over the railing watching the trolley. If you were to push him over the footbridge he would tumble down and smash on to the track below. He’s so obese that his bulk would bring the trolley to a juddering halt. Sadly, the process would kill the fat man. But it would save the other five.

Would you kill the fat man? Should you kill the fat man?

The reference to the man’s obesity is not gratuitous. If the train could be stopped by anybody of any size, and if you’re standing next to the fat man, then presumably the proper action is not to push the fat man, but to leapfrog over the railings and sacrifice yourself. A courageous and selfless act, but in this example, it would be a futile gesture:

ex hypothesi

you are not bulky enough to stop the train.

Figure 2

.

Fat Man.

You’re on a footbridge overlooking the railway track. You see the trolley hurtling along the track and, ahead of it, five people tied to the rails. Can these five be saved? Again, the moral philosopher has cunningly arranged matters so that they can be. There’s a very fat man leaning over the railing watching the trolley. If you were to push him over the footbridge, he would tumble down and smash on to the track below. He’s so obese that his bulk would bring the trolley to a shuddering halt. Sadly, the process would kill the fat man. But it would save the other five. Should you push the fat man?

Even though the man’s size is a necessary component of the thought experiment, and even though he is fictional, drawing attention to his scale is considered by some to be indecent.

Thomson introduced us to the fat man in an article in 1985, when academics had long internalized the need to be cautious and sensitive about prejudice and language, particularly as it pertained to race, religion, sex, and sexuality. The obese, however, were not seen as a self-identifying group subject to discrimination and in need of linguistic policing. By 2012, a UK parliamentary body was recommending that calling someone fat be deemed a “hate crime.” And in many of the articles about trolleyology, the fat man has undergone a physical, or at least a conceptual, makeover: he has become a “large” man, or a “ “heavy” man, or a man of girth. Better still, for those easily hurt, a near-duplicate philosophical problem has been devised that removes the need to allude to the potential victim’s corpulence. This time you’re standing on a footbridge next to a man with a heavy backpack. Together, the man and his bag would stop the train. Of course, there’s no time to unstrap the backpack and jump over the bridge wearing it yourself. The only way to save the five is to push the man with the bag.

However described—and I am going to refer to the fat man with his traditional label—it looks, once again, as though the DDE might help explain the typical moral intuition here: that we can turn the train in Spur but not push the fat man (or man with bag). As previously argued, in Spur you don’t want to kill the man on the track. But with Fat Man, you

need

the obese man (or the man with the heavy bag) to come between the trolley and the five at risk. If he were not there, the five would die. He is a means to an end, the end of stopping the trolley before it kills five people. It would be a noble sacrifice if the fat man were to jump of his own accord.

2

But if you push him you are using him as if he were an object, not an autonomous human being.

Like Philippa Foot, however, Thomson was told not to resort to the DDE to explain the difference. She wanted to appeal to the notion of “rights.” Like Foot, she was preoccupied with one of the touchstone issues of the day, abortion, and had already appealed to rights theory in her most famous article on the subject, “A Defense of Abortion.”

3

This article imagined that you wake up one day lying next to a famous violinist, both of you plugged into a machine. The violinist had had a fatal kidney ailment. On discovering that you alone have the right blood type to help, the Society of Music Lovers hooked the two of you into a contraption so that your kidneys could be used by him as well. Medical staff explain that, regrettably, were the violinist to be unplugged, he would die but, not to worry, this awkwardness will only last nine months, by which time he’ll be back to normal and the two of you can go your separate ways. Thomson’s claim was that it might be very nice of you to permit the violinist to remain yoked to your body, but he or the hospital would have no

right

to insist that you do so.

Likewise, Thomson appealed to rights in Fat Man. Toppling the fat man is an infringement of his rights. But turning the trolley in Spur is not an infringement of anybody’s rights. “It is not morally required of us that we let a burden descend out of the blue onto five when we can make it instead descend onto one.”

4

The bystander is not just minimizing the number of deaths by turning the train down the spur; he or she is minimizing “the number of deaths which get caused by something that already threatens people.”

5

Note the similarity to Foot’s argument that in Spur one is merely redirecting a preexisting threat, whereas pushing the poor fat man introduces a completely new threat. This distinction feels plausible: it feels as if it should carry some moral weight. But one trolleyologist

6

insists it does not. She offers, as evidence, Lazy Susan.

7

Figure 3

.

Lazy Susan.

In Lazy Susan you can save the five by twisting the revolving plate 180 degrees—this will have the unfortunate consequence of placing one man directly in the path of the train. Should you rotate the Lazy Susan?

In Lazy Susan, you can save the five by twisting the revolving plate 180 degrees—this will have the consequence of placing one man directly in the path of the train. Nonetheless, says the inventor of this scenario, it’s permissible to turn the lazy susan—even though this is not about diverting an existing threat; for the individual who will die, it introduces an entirely new threat.

Figure 4

.

Loop.

The trolley is heading toward five men who, as it happens, are all skinny. If the trolley were to collide into them they would die, but their combined bulk would stop the train. You could instead turn the trolley onto a loop. One fat man is tied onto the loop. His weight alone will stop the trolley, preventing it from continuing around the loop and killing the five. Should you turn the trolley down the loop?

You may not share that intuition. If you do, the search for a principle to explain our other intuitions in Fat Man and Spur

continues. But what’s wrong with the DDE as the answer? Why wouldn’t Thomson appeal to that? Well, because of a trolley problem she invents that we can call Loop.

A number of weeks have passed since you were faced with an instant and excruciating choice in Spur of whether to turn the train down the side track. Then, you made the correct decision: you turned the train. In the interim, workers have extended the side track, so that it circles around back to the main track. Once again you’ve gone for a walk and find yourself in the midst of a similar nightmare, though with a slight modification. In Loop, the train is heading toward five men who, as it happens, are all skinny. If the train were to collide into them they would die, but their combined bulk would stop the train. You could instead turn the train onto a side track. The side track has one fat man. His weight alone will stop the train, preventing it from continuing around the loop and killing the five. There’s this key difference. In Spur, if the single man were to escape, that would—in the much lampooned words of the German philosopher Gottfried Leibniz—be the best of all possible worlds.

8

Not so in Loop. In Loop, if the man on the side track were to disappear, the five skinny men would be killed: this time you need his death to save the five. The collision with this man is therefore surely part of your plan.

Nonetheless, writes Thomson, given that we agree that it would be acceptable, if not obligatory, to turn the train in Spur, it must be equally acceptable to do so in Loop, for, as she puts it, “we cannot really suppose that the presence or absence of that extra bit of track makes a major moral difference as to what an agent may do in these cases.”

9

If Thomson is right, the DDE cannot be the principle to justify a distinction between Spur and Fat Man.

10

For in Loop we don’t merely foresee the fat man’s death: we need the fat

man to die—we intend his death. Turning the trolley in Loop falls foul of the DDE.

So it looks as if we’ve hit the buffers again. We have identified a common intuition that it is sometimes wrong to take a life even though five lives would be saved. Can we ground this intuition in principle? The attempt to do that takes us back to the eighteenth century and the remote Prussian outpost of Königsberg.

CHAPTER 6

Ticking Clocks and the Sage of Königsberg

Out of the crooked timber of humanity no straight thing was ever made.

—Immanuel Kant

AN ELEVEN-YEAR-OLD BOY has been kidnapped. He was last seen getting off the Number 35 bus on his way home on the final school day before the autumn holiday. He’s now been missing for three days and is considered to be in mortal danger. The police have arrested the chief suspect. He was captured after picking up a ransom of one million Euros. The ransom had been demanded in a note left on the gate of the boy’s home—and had been dropped, as agreed, at a trolley stop on a Sunday night. Instead of releasing the boy, the man went on a spending spree with his million Euros. He booked a foreign holiday; he ordered a C-class Mercedes.

The police are as certain as they can be that they have the guilty man—a tall, powerfully built law student, who’d previously been employed to give the boy extra tutoring. Now they urgently need to locate the boy. They don’t know how long they have to save his life: is he locked away in a cellar, without

access to water and food? The interrogation of the law student begins: the clock ticks—and ticks, and ticks, and ticks. A search involving 1,000 police, helicopters, and tracker dogs yields nothing. And, after seven hours of questioning, the suspect has still not given up the boy’s whereabouts.

The police officer in charge writes down an instruction to the interrogators: they are to threaten to torture the suspect. “A specialist” will be flown in, they tell the suspect, whose function it will be to inflict unimaginable pain until they extract the information they need.

The suspect cracks. He reveals where the boy is being held.

An Icy Gust

This kidnapping occurred in Germany in 2002. The kidnapper was Magnus Gäfgen, a law student in his mid-twenties. The victim, Jakob von Metzler, was the heir to a fortune: his father ran Germany’s oldest family-owned bank.

The story does not have a happy ending. Frightened, under pressure, faced with a horrifying ordeal, Gäfgen told the police that Jakob could be found at a lake near Frankfurt. When they arrived, they discovered the boy’s body: he’d already been killed, and was in a sack, wrapped in plastic and still dressed in the blue top and sand-colored trousers in which he’d last been spotted.