X and the City: Modeling Aspects of Urban Life (74 page)

Read X and the City: Modeling Aspects of Urban Life Online

Authors: John A. Adam

=

V, A

: WINSLOW REVISITED

We finish this chapter about the “somber possibility of very serious things happening” on a more light-hearted note. The Winslow crater is

now

about 170 m deep and 1250 m across. You’ve heard of ships in a bottle? How about building a town in a meteor crater? The base of the crater, not being entirely flat, would probably have to be leveled, but ignoring this practical concern, we assume this has been done, and calculate the base area to be just over 1 km

2

. This is far too small to accommodate more than a small town with the population density of the New York metropolitan area (about 2000 people/km

2

). Well, if not a city, how about a stadium? This would be a most appropriate place to hold

rock

concerts.

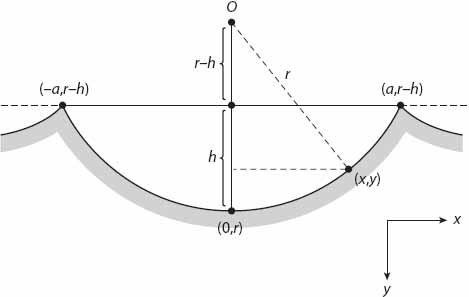

We can also use integral calculus to determine the volume and surface area of the (idealized) circular crater [

42

] of diameter 2

a

and maximum depth

h

. We suppose that it is, as it were, a portion of the inner surface of a sphere of radius

r

and center at the origin

O

(see

Figure 24.1

).

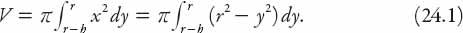

First, the volume:

After a little algebra, and using the result

we find that (

Exercise!

)

Figure 24.1. An idealized cross section of the Winslow meteor crater.

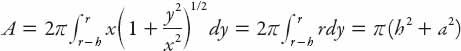

The area is found in a similar manner (

Exercise!

), thus:

So: plugging in the values

a

= 625 and

h

= 170 we find that

V

≈ 1.0 × 10

8

m

3

and

A

≈ 1.3 × 10

6

m

2

.

Exercise:

Given that the density of the ground material at the crater is about 2350 kg/m

3

,

mentally

calculate the mass displaced by the meteor.

Suppose that an institute of higher education, Laid Back State University (LBSU) decides to build a football stadium in the crater. LBSU could be any such institution in the United States, of course. (The one at which I am employed is about 2000 miles from Winslow, Arizona. This is considered to be “local” on the scale of the Solar system.) Allowing 15% of the total area to consist of stairs, aisles, restrooms, and hot-dog stands and the rest for the football field, and allowing 75 cm

2

for each seat, the crater can accommodate (0.85 × 1.30 × 10

6

)/(0.75)

2

≈ 2 × 10

6

people—this is just a tad larger (a hundred times!) than the recently built football stadium at Old Dominion University, which holds just under 20,000 people at maximum capacity. We still have a way to go.

GETTING AWAY FROM THE CITY

After endless days of commuting on the freeway to an antiseptic, sealed-window office, there is a great urge to backpack in the woods and build a fire.

—Charles Krauthammer

Why would one wish to get out of the city, at least for a time? To escape the possible impending doom discussed in the previous chapter? There are many other reasons why we might wish to take a break from city life, such

as dissatisfaction with continued traffic congestion and the hectic pace of life, or just a desire to experience nature in all its variety. My favorite seasons are spring and fall (autumn). The season of autumn can be one of great beauty, especially where the foliage changes to a bright variety of reds, oranges, and yellows.

It’s a bit of an aside, but why do leaves change their colors in the fall? There are in fact several different reasons, but the most important is the increasing length of night and cooler temperatures at night. Other factors are the amount of rainfall and the overall weather patterns in the preceding months. Just like sunsets, the weather before each fall is different. Basically the production of chlorophyll slows and stops in the autumn months, causing the green color of the leaves to disappear, and the colors remaining are mixtures of brown, red, orange, and yellow, depending on the types of tree. To have any real chance of seeing the wonderful fall foliage, you have to go to the right places at the right time. Going to the beach in summer or even the fall won’t do! And going to the Blue Ridge Mountains or New England in the depths of winter will not enable you to see the fall foliage either, pretty though the snow-covered trees may be!

But there are some other aspects of this season that are present at any time of the year, and do not depend on the leaves changing. Those aspects involve trees, rain, and, in this case, my left foot!

Consider this: you are in the hills of New Hampshire, or West Virginia, or perhaps you are somewhere on the Appalachian Trail enjoying the glorious fall colors, when suddenly a rain squall appears out of nowhere (or so it seems). You run to take cover in a deserted shelter a hundred yards away near the trail. Playfully (there being nothing else to do) you stick your foot outside the shelter, and of all things, photograph the rain falling around it!

After ten minutes of intense rainfall, it stops as suddenly as it started. You wonder how fast that rain must have been falling to create the scene you now survey: large puddles all along the trail, drops dripping from every available leaf above you, and the temporary dark-brown stains on the trunks of rain--soaked silver birches.

As you set out on your way again, you start to notice the wave patterns formed when the drops falling from the branches above you hit the surface of puddles.

Question:

Which of the patterns in

Figures 25.1

and

25.2

represents this situation?

Figure 25.1. Circular wave pattern I—caused by raindrops?