Year of the King: An Actor's Diary and Sketchbook - Twentieth Anniversary Edition (30 page)

Read Year of the King: An Actor's Diary and Sketchbook - Twentieth Anniversary Edition Online

Authors: Antony Sher

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Performing Arts, #Theater, #Acting & Auditioning, #Stagecraft, #Biographies & Memoirs, #Arts & Literature, #Entertainers, #Humor & Entertainment, #Literature & Fiction, #Drama, #British & Irish, #World Literature, #British, #Shakespeare

The scene is taking shape at last. The cackling, sinewy excess of that

dreadful rehearsal has been quietly forgotten. No one has mentioned it

since.

QUEEN ELIZABETH SCENE Bill says we must be aware of reducing

this scene by resorting to modern English behaviour - reticence, impatience, and so on. `This confrontation has no equivalent in contemporary

England. Maybe in Amin's Uganda. The meeting between a mother and

a man who's killed her children. A special intimacy, even beyond hatred.

A dreadful intimacy. Maternalism versus Power.'

He says that Richard wins her round because he has a brilliant instinctive

understanding of psychology. Queen Margaret, a few pages earlier, had

been urging Elizabeth to bottle up her pain until it drives her mad. But

Richard knows how to bleed her, to let her poisons out.

Also, Richard understands her fundamental materialism. Bill says that

I'm doing the bargaining section ('The liquid drops of tears that you have

shed shall come again, transformed to orient pearl') too prettily: `Richard

is saying to her, "Look love, I can turn your tears into jewellery."'

This gives the scene a much more disturbing quality.

V o t C E CALL I wish I could remember exactly how Ciss put it: the ideas

rest on the breath, both come out open and free. (She said it much better

than that.) How the humour will be spontaneous that way, not planned

or arch.

She makes me do the speeches sitting on the floor rocking. Says the

voice instinctively goes to its proper centre that way, the breath coming

from the diaphragm.

She makes Roger and me sing our duologue as an operatic duet.

Freeing, freeing all the time.

Ciss: `In the last two or three years the R S C has started to underestimate

audiences. Shakespeare is easier to understand spoken at speed rather

than slowly spelt out.'

I'm developing a stiffness in the left hip. Is this from adjusting to the rake,

or is it the deformed position itself? Will have to keep a careful check on

this.

SOLUS `Now is the winter' with Bill and Ciss. The main problem is the

first section of the speech. Bill suggests doing it as if Richard is having to

address a public function on behalf of his brother, the King, having to

disguise his own feelings about peace. Then we try taking that one stage

further, a kind ofJackanory treatment, `Once upon a time . . .' I like this.

At last something to grasp on to. And it has a kind of anarchic defiance:

saying to the audience, `I know you've all heard this speech before, so

here we go.' But Bill thinks that is too dangerous to play, wants it to

remain more enigmatic.

I do the deformity section full of aggression and self-hatred. Again Ciss

says, `You're telling us too much.'

I try the whole speech internalising the feelings, making the sections

less distinct; in other words, acting less. Immediately feel the character

coming through the lines unexpectedly, freshly, not being illustrated on

top of them. `That's more like it!' cry Bill and Ciss in unison.

This has been a breakthrough. We work on through all the speeches,

everything now that much easier. For the first time tonight I didn't feel

frightened by the soliloquies; more than that, I actually felt comfortable

in them. What's happening is that I am surrendering to Shakespeare's

Richard. He is funny.

A letter from Bob today with a well-timed quotation from Shaw about

good Shakespearian acting. He's writing about Forbes Robertson as

Hamlet: `He does not utter half a line; then stop to act; then go on with

another half line; and then stop to act again, with the clock running away

with Shakespeare's chances all the time. He plays as Shakespeare should

be played, on the line and to the line, with the utterance and acting

simultaneous, inseparable, and in fact identical. Not for a moment is he

solemnly conscious of Shakespeare's reputation or of Hamlet's momentousness in literary history; on the contrary, he delivers us from all these

boredoms instead of heaping them on us.'

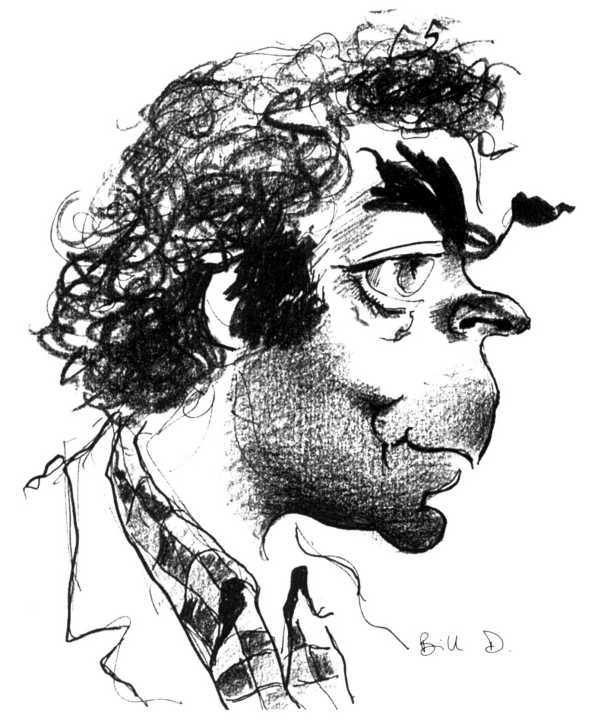

DIRTY DUCK I ask Bill D. when we're going to have a session in the

make-up department to work out the facial prosthetics. He says, `I'm not

sure it's necessary any more.'

`What, you mean, no nose?'

`No nose.'

`Oh well, I suppose I was going off the idea too. Just the cauliflower

ears then?'

`No.'

`What, you mean, no ears?'

`No ears.'

`All right, tell you what, how about eyebrows? Huge eyebrows meeting

in the middle. Like yours.'

`No.'

`No eyebrows?'

`No eyebrows.'

`He's going to look like me at this rate.'

`Why not? Your image of the brute is for another actor. Anyway, isn't

that how the Russians played him?'

It's a shock to realise that, in pulling away from Olivier, I was simply

backing into the arms of Chkhivadze.

So we have agreed to use my own face. Richard is coming up from

within now, not painted on top.

Thursdays at the R S C are a write-off. Matinee day, so most of the cast

have to break at 11.3o a.m. to have their two-hour Equity break. Which

means me doing more solus calls, or busking through scenes with perhaps

one other actor, and Bill running round being everyone else.

But a chance to get to the gym again. The ache in the hip is less today.

I'm sure it was having to adjust to the rake. However, it has been a

warning. I must increase my fitness programme again. I've been neglecting

it to give more time to learning lines.

CANTEEN Lunchtime. When you order your food they write it next to

your name, then call you when it's ready.

Sebastian Shaw is in front of me in the queue. He gives his order to

the girl and is about to go when she says, `Sorry, what's your name?'

He stops in his tracks. Looks at her. Turns to us in the queue, says,

`She doesn't know who I am.'

The girl blushes. `Sorry, I'm new here.'

`Sebastian Shaw,' he says, almost apologetically.

An odd, sad incident. He wasn't being arrogant. He's nearly eighty, has

been with the Company longer than anyone in the building, and they

don't know his name.

He's full of the most thrilling stories. At school, W. H. Auden played

Katherina to his Petruchio. When he first arrived in Stratford for the

1926 season (he was playing Romeo, Hal and Ferdinand) he found the

theatre had just burnt down. They had to play in a cinema. George

Bernard Shaw used to sit in the front row making comments and causing the audience around him to giggle. Sebastian says, `As far as my namesake

was concerned, the world had only known two great playwrights. Shakespeare and Shaw. And he did not put them in that order either.'

As for Shakespeare, Sebastian says, `Whenever I come up here for a

season I like to go into Trinity Church, usually when there's no one else

about, and stand in front of his tomb. Just stay there for a while. You

know, in astonishment.'

MOTHER SCENE I come into the Conference Hall to find Bill and

Yvonne Coulette cutting her long speech about Richard's birth and youth.

I implore them to leave it intact.

Bill, grinning: `And this is the man who sits me down in the pub every

night and begs me to cut, cut, cut.'

`But not Richard's mother!' I say. `The man's entire psyche is explained

in this scene. Cut "Now is the winter" if you like, but not a comma from

this scene.' I argue how brilliant Shakespeare was to reduce the scale to

the domestic at this point.

Bill puts it better: `It reminds us that Hitler was a baby in someone's

arms, a little boy on a school playground.'

The speech goes back intact.

Yvonne's instinct, quite naturally given the lines, is to play the scene

vehemently, aggressively. I feel it has to be odder than that. All the women

in the play curse Richard. Water off a duck's back; the mother has

somehow to turn him inside out. Bill agrees, and encourages Yvonne to

be gentler, more maternal: `Let him hear something in her tone that takes

him right back into the nursery, a woman's voice singing gently, rocking

him. That's the cruellest thing she can do to him now. Let her entice him

into the curse. She's the spider now, he's the fly for a change.'

Building on this idea, Bill suggests that, once she has persuaded him

to have the throne lowered to the ground, she should offer a hand and

lead him gently on to the floor, to kneel together in prayer. He wasn't

expecting to be moving about, so is without his crutches. Vulnerable. Now

she can let rip.

Yvonne tries this version, but it's difficult - it means playing against the

lines with all she's got. At the end of the curse her instinct is still to throw

Richard's hand aside, or to go to strike him.

I beg her to try a kiss, a kiss implanted with the most maternal intimacy

(I'm in fulsome Freudian mood now).

She looks to Bill imploringly, says, `I feel she might want to, but she

can't.'

Bill: `What if she wants to, and can?'

Yvonne tries it. It is electric.

Monty was directing this scene.

Bill D. has been to Chris Tucker's today. He returns with polaroids of the

enlarged arms, which look magnificent. He's given Tucker the go-ahead to

cast it all into latex, without building up the back at all. He says, `Following

our conversation last night about normalising Richard, I think Tucker

may have got it right.'

I have the evening off to pace my little Godot set and learn the last of

the lines: the nightmare speech and `A horse, a horse'. About the latter

we made these two fascinating and irrelevant observations the other day:

one, that it's the only bit of the play we haven't yet staged; two, that it's

probably the second most famous line in the whole of Shakespeare ('To

be or not to be' is probably in first place).

So now all the lines are learned. Roughly.

RICHARD AND BUCKINGHAM Bill, Mal and I spend the evening on

the various sequences that make up this relationship. A marvellous relaxed

evening, like old times with old friends.

All three of us have, I think, been behaving rather untypically in front

of the new Company. Tension, I suppose. Bill and I have been sniping at

one another, increasingly irritated by one another's weaknesses which we

know all too well; Mal still tends to go into his aggressive silences.

But left on our own tonight, all of that disappears. Bill rushes around

peering through an imaginary viewfinder and getting it wrong - holding

it up to the closed eye - like he did in the telly rehearsals at Acton. Mal

plays Buckingham very camp, flouncing around with hands propped high

on his rib cage. It is an awesome sight - a camp Viking. I just stand there

and laugh.

Good discovery for the Baynard's Castle scene: with the gentlest

re-arranging of lines we contrive to bring Richard down from that upper

window and hence break up the static nature of the scene. That's been

one of the most cumbersome factors - Buckingham having to deliver his

long speeches to a man behind and above him. Now Richard can be on

stage level with the mayor and aldermen. This would also seem an ideal

opportunity for him to function without his crutches for a while - increase

his impression of harmlessness, vulnerability.

A R D E N HOTEL BAR Mal relates an interesting historical fact dug up in

Henry V rehearsals: the two-fingered sod-off sign comes from Agincourt.

The French, certain of victory, had threatened to cut off the bow-fingers

of all the English archers. When the English were victorious, the archers

held up their fingers in defiance.

This could be useful. The other day, rehearsing the `Was ever woman'

speech, Alison Sutcliffe suggested I count the pros and cons on my fingers

to emphasise the audacity of what Richard has managed to pull off. He

only had two things going for him and they're ironic ('And I no friends

to back my suit at all but the plain devil and dissembling looks') so the

idea was for him to use two fingers in a V-sign. Until tonight, I had

dismissed the idea as being too modern.

My favourite part of the day is the drive into Stratford. As you come up

out of Chipping Campden you go over the brow of a hill. It's so beautiful

I always risk crashing at this point, particularly as I try to time putting in

the cassette at this moment. Today it is Delius. The world below is

particularly spectacular this morning. The fields of rape - I will never tire

of trying to describe them - are the gold at the end of the rainbow. The

car roof open, a warm breeze blowing, a taste of summer, the magnificent

copper beeches, white and red fruit blossoms.

PRINCES SCENE Richard and Buckingham's double-act at its most

sublime. Richard sits back and lets Buckingham deal with each problem

as it comes up - the Queen taking sanctuary, the boys' questions about

Caesar, the interrogation of Catesby. Mal says, `You keep passing the

Buck and I'll supply the Ham.'