Year of the King: An Actor's Diary and Sketchbook - Twentieth Anniversary Edition (28 page)

Read Year of the King: An Actor's Diary and Sketchbook - Twentieth Anniversary Edition Online

Authors: Antony Sher

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Performing Arts, #Theater, #Acting & Auditioning, #Stagecraft, #Biographies & Memoirs, #Arts & Literature, #Entertainers, #Humor & Entertainment, #Literature & Fiction, #Drama, #British & Irish, #World Literature, #British, #Shakespeare

`It's not Wimbledon!' cries Bill. `And you're wafting! I don't want to

see any wafting! No ghost acting!'

The ghosts are going to come up out of the tombs, which have secret

back entrances, so each new ghost joins the group from behind. This

means the others have to sense his presence and make a natural parting

for him. Inevitably, ghosts crash, trip, get tickled and goosed, Blessed

burps and farts.

`English actors,' laments Bill afterwards, `English actors are so selfconscious. There'd be no problem with that scene if you had continental

or American actors.'

MOTHER SCENE (Act rv, Scene iv) We have a brief look at this vital

scene. Bill has a nice image for when Richard calls for his drummers and

trumpeters to drown her out: `A petulant boy turning up the hi-fi.'

PRINCES SCENE After further consultations with Tucker, we have

decided to abandon the piggyback ride and go for the Brando/gorilla

version instead. The young York says, `Because that I am little like an

ape, he thinks that you should bear me on your shoulders!' ... Richard's

face goes blank, he rises slowly, pauses, and then defuses the tension with

the gorilla act.

One of the older boys, Rupert Finch, says, `Wouldn't it be better if you

turned away so that we couldn't see what you're thinking? As if you were

shunned. And then suddenly turn back and be the gorilla. It would be

more surprising.'

He's quite right. It is much better. `So wise, so young, they say ...'

SOLUS The nightmare speech. Bill says, `It's about fear in a very personal

way. We mustn't talk about it too much. Anyway there's not a lot I can

say. I know what it means to me, but it's got to be your personal expression

of terror. We must just let it happen gradually.'

A stocktaking on the disability. As I'm coming off the book I'm experimenting more and more with the polio walk.

`Oh it's polio, is it?' says Bill. `I've been wondering what you've been

doing. Lucky we're having this discussion.' He feels it's too disabled, too

extreme a difference from the speed and agility on the crutches. He'd

prefer the disability to be less specific - he suggests bone damage caused

by the difficult birth - but basically strong and capable.

I feel no sense of wasted research. Everything seeps together. The new

walk, for example, immediately becomes slightly spastic, which I thought

I had ditched as an option.

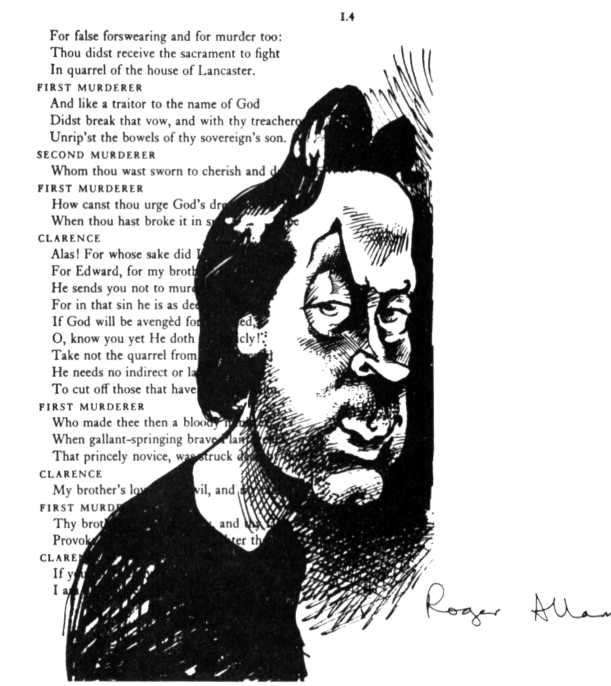

ARDEN HOTEL BAR With Bill and Roger Allam, who is a joy and one

of the best verse-speakers in the Company. I call him The Voice Beautiful

and he calls me The Body Busy (the other day he said, `I wouldn't like

to see you in Whose Life is it Anyway!'). I outline Monty's theory about

Richard and his mother. Bill is very taken with this.

A had day.

QUEEN MARGARET SCENF. This morning Bill comes in and talks to

the cast about finding more tribaL'animal behaviour. Getting away from

the stiff formality of history-play acting.

Bill has always been open about how uncomfortable he feels with

improvisations, workshops and exercises. Unfortunately, for something

like this, it's the only way. Instead Bill suggests running the scene, `trying

to be more bestial'.

The result is a disaster. Behaviour not from the animal world but the

world of pantomime. Cackling laughter, food being thrown around, sinewy

`wicked' acting. Although I'm participating and probably responsible for

some of the worst excesses, I can hardly bear to watch the others. Have

to bury my head on the crutches for much of the scene. In one fell swoop

there is a vision of how ludicrous this play can be if we don't get it right.

The endless suffering, squabbling and cursing. Unintentionally, we've

made it funnier than the Liverpool production, which was trying to be

funny.

The rehearsal ends with extreme dishonesty. We all mutter the usual

bullshit ('Well, we've got a good basic shape to work from') instead of

sitting down and saving, `That was terrible, that was embarrassing, we

must never be so had again.'

On to the King Edward scene (Act u, Scene i) and then the scene with

Clarence's children (Act ii, Scene ii), and worse and worse it gets. These

are difficult scenes - people are dying left, right and centre, news of death

being broken to brothers and children; wives and mothers in grief. So

much acting going on. We're only at the beginning of Act Two and already

every emotion known to man (or rather those unknown to man, but loved

by actors) has been laid bare on the stage.

Feel very shaken by lunchtime. I fear that it's partly my fault. I've been

acting too much too soon, starting with all that shouting at the read-through.

People might be taking their cue from me: emoting instead of investigating.

But we have also uncovered a dangerous trap in the play; it gives many

of the characters A Big Moment. And, as actors, we love this - our chance

to do a mini-Lear, Macbeth, Lady Macbeth, Coriolanus, Volumnia. That

must be resisted or the story won't be allowed to flow. And anyway, we'd

be laughed off the stage.

Find Bill and pour out all of this. His eyes glaze over, the flesh on his face drops at least an inch and turns to putty. He says, `It wasn't that

bad. You're over-reacting. You must allow everyone their own rehearsal

process.'

I go away realising that this has been another symptom of the fear. The

scenes were terrible, but there is no need for panic yet.

I must steady myself.

We are at that tricky stage: we're putting down the scripts, the lines are

dragging in our heads rather than dancing. Everything feels exposed and

faintly embarrassing. The scripts have been little shields up until now.

Blessed says, `It's the time to be brave.'

Go into rehearsals determined to take things slower, to act less, to question

more, particularly the moments of horror.

The result is a much better day.

STRAWBERRY SCENE (Act III, Scene iv) Long discussion about what

Richard does here. He has to burst into the Council Chamber saying that

he's suddenly been bewitched, produce his withered arm as evidence and

accuse Queen Elizabeth and Mistress Shore of witchcraft. Shore is

Hastings's lover and so in this roundabout way Hastings is implicated and

condemned to death. It makes no logical sense at all. It's pure bravado

on Richard's part. Ironically, this does demand acting of the most spectacular sort, all guns firing, so impressive and so fast that no one has a chance

to say, `Hang on, you've always had that withered arm.'

It's generally agreed that the way we've found of doing this - smashing

one of the crutches down on to the council table, Richard imagining this

thing to be a withered arm - is effective in the way that the scene demands,

and not ludicrous.

To increase the illusion of Richard being possessed, I suggest that he

should come in vomiting - he's not above putting a couple of fingers down

his throat for effect. But Bill feels that this would be going too far.

Thus we proceed with caution, step by step.

HASTINGS' HEAD SCENE The budget cannot stretch to another Tucker

creation, but we are assured that the Prop Department will excel themselves. It will have the correct weight and floppiness of a freshly severed

head.

How to bring it on stage? Bill A. suggests it is stuck on a pike, covered by a cloth which is then whipped off. This will surely get a laugh. It will

be like a magic trick. His next suggestion is that it be uncovered on the

pike dripping into a large tray underneath. Bill D. feels this will be too

much like a kebab. He suggests one of the soldiers carry it on by the hair.

Better.

What about the business of putting the head into the mayor's hands,

and passing it about? This will definitely get laughs. Are they valid? Not

sure. All I know for certain is that we must be able to shock when we

want, make them laugh when we choose. My fear from yesterday's terrible

rehearsals is us being laughed at.

BAYNARD'S CASTLE Still tedious. Why, why, why?

FIGHT REHEARSAL I hate to say it but I'm losing faith in the idea of

the crutches. They get in the way so much. I can't reach for things or

carry anything. They are very disabling (which I suppose is the point, but

also a drag). Will it get easier with practice? More to the point, are the

sodding things a good idea and worth pursuing or not? The main worry

about losing them altogether is the point Charlotte made about the

disability: it's safer when played on crutches.

We have all agreed that if they are to work they must be employed early

on in the play as weapons. The earliest opportunity is the beginning of

the Lady Anne scene when Richard stops the funeral procession and is

challenged by the guards. Shakespeare doesn't indicate a fight here but,

with a tiny snip at the text, one is easily contrived. It needs to be short

and vicious. Richard's blows must be sadistic beyond the call of duty.

Stage violence is one of my bugbears. You hardly ever see it done well

enough. Because the fights have to be choreographed so carefully and the

blows pulled or cheated, a kind of balletic stylisation takes over. Most

stage fights are rather graceful. They lack the scrabbling ugliness of real

violence. Also a shorthand develops in playing pain. We often forget to

consider the agony that a mere stubbed toe or bumped head can cause.

Actors will take bone-crushing blows, do a token `Argghh!', get up and

stroll away.

But Malcolm Ranson is one of the best fight directors in the business.

The usual problem - where to strike on the body? He devised a very

effective metal backplate for Chris Hunter, as Oswald in King Lear, so

that his back could be broken with a staff. One of the guards can have

this. The target is large and I can swipe at it with full strength. With the other guard we devise a jerky scrabble across the stage - when animals

fight those little charges and retreats are as vicious as the actual contact.

But then the problem is where to hit him? We are face-on so all the targets

are delicate areas. Eventually settle on a jab to his stomach. He can

catch the crutch as I swing it and then control the impact of the blow

himself.

The monks carrying the bier suggest that they could have crash helmets

under their cowls and I could lay them all out as well. Bill says that he

has no intention of playing the rest of the scene, one of Shakespeare's

most famous, among a pile of dazed monks.

Malcolm Ranson is disappointed to hear we won't be doing a big fight

between Richard and Richmond at the end. He wonders whether the

structure of that last section of the play doesn't demand a piece of action.

(Shakespeare does indicate a fight here.) But Bill is convinced that if we

can find the right image for a ritual slaughter of Richard, that would be

more effective.

LADY ANNE SCENE Excellent rehearsal. At one point Penny gets angry

with herself and says, `I'm acting too much!' I could hug her. Bill being

very helpful to me today, curbing over-acting. Yesterday's fiasco is proving

valuable. He reminds me how dangerous animals are when they become

very still and poised.

At the end of rehearsals he whispers to me, `Beware this scene doesn't

peak too early.' The instant rapport Penny and I have as actors is causing

things to fall into place too easily. What a pity there aren't more Richard/

Anne scenes throughout the play. He suggests we lay off the scene for a

while.

Poor Bill is in agony. He's done something to his back - someone said

it's the Richard III curse - and has to rehearse while clutching a hot water

bottle behind him.

I'm very pleased with my work today. I'm using my uncertainty with the

lines to be quieter, to investigate more, to think and feel. It's an unfamiliar

way of working, but rather good. Will pay dividends.

s O L v s Embarrassing doing these speeches sometimes. You feel like

you're auditioning.

We work on `I do the wrong, and first begin to brawl'. Bill has a nice

image - it is The Story So Far. A lovely idea, but a light and jokey one. Moving further and further away from the man's pain. There is still this

basic contradiction to be solved.

KING RICHARD'S COURT SCENE (Act iv, Scene ii) This begins our

second half. It's where Buckingham gets the elbow and Tyrrel is hired to

kill the Princes. Bill's idea of having Lady Anne sitting there, white and

semi-poisoned, is going to work marvellously. Shakespeare doesn't have

her in the scene, but it will be a strong image - this silent, sick presence

at Richard's side. Penny sits with eyes opened, but sightless. `Valiumed

out of her mind,' as she describes it. She also talks about a practice in

Australian aboriginal witchcraft - `pointing the bone' at someone to

make them die (the power of suggestion). She says that Lady Anne has

inadvertently done this to herself: in her first speech one of her curses

against Richard was directed at his future wife.

Driving into Stratford to meet the Bills for another visit to Chris Tucker's.

A pink smoky dawn, mist billowing across an icy field of rape and up the

side of Meon Hill where black magic killings take place.