1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created (32 page)

Read 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created Online

Authors: Charles C. Mann

Tags: #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies), #Expeditions & Discoveries, #United States, #Colonial Period (1600-1775), #History

Click

here

to view a larger image.

Zhejiang censor Wang Yuanfang couldn’t understand it. In the past, he knew, landlords hadn’t understood that renting their unused upland property would have disastrous consequences.

“Now

[in 1850]

the waterways are filled with mud, the fields are buried under sand, the mountains reveal their stones and the officials and people know of the great disaster, but they do nothing to stop it. Why?”

(Emphasis in original.)

In part, the failure was due to an inherent problem with mass illegal immigration. It is not easy to deport huge numbers of people—tearing them from homes and families built up over years—without mass suffering. Governments that seek popular support shrink from inflicting this kind of agony (unless the loss of support from one group is made up for by increased support from another). Logistically, there is also the problem of finding a destination for people who have left their original homes decades before. In the case of the shack people, Osborne argued, neither governmental queasiness nor confusion was the chief obstacle. The main problem was that the erosion represented a classic collective-action problem. A legal loophole ensured that rental income, unlike farm income, was tax free. Landowners with rentable property in the highlands thus had an easy source of untaxable income. The ensuing deforestation might ravage their own fields in the valleys, but the risks would be spread across an entire region, whereas the landowners’ profits were theirs alone. Absorbing all of the gain and only a fraction of the pain, local business interests beat back every effort to rein in shack people.

In an environmentalists’ nightmare, the shortsighted pursuit of small-scale profit steered a course for long-range, large-scale disaster. Constant floods led to constant famine and constant unrest; repairing the damage sapped the resources of the state. American silver may have pushed the Ming over the edge; American crops certainly helped kick out the underpinnings of the tottering Qing dynasty.

Other factors played their part, to be sure. A rebellion led by a Hakka mystic tore apart the nation, briefly setting up a state of shack people in the Hakka hills of the southeast. A series of weak emperors allowed the bureaucracy to wallow in inanition and corruption. The empire lost two wars with Great Britain, forcing it to cede control of its borders. British forces freely disseminated the opium that the government had gone to war to exclude. And so on—catastrophe, like success, has many progenitors. Unknown to the rampaging European armies, though, their path had been smoothed by the Columbian Exchange.

UNLEARNING FROM DAZHAI

For two generations, one of the most celebrated places in China was Dazhai. A hamlet of a few hundred souls in the dry, knotted hills of north-central China, Dazhai was ravaged by floods in 1963. Standing in the wreckage with his signature sweat-absorbing towel around his head, the local Communist Party secretary refused aid from the state and instead promised that Dazhai would rebuild itself with its own resources—and create a newer, more productive village at the same time. Harvests soared, despite the flood and the area’s infertile soil.

Delighted by the increase, Mao Zedong bused thousands of local officials to the village and instructed them to emulate what they saw. Mainly, they saw spade-wielding peasants working in a fury to terrace the hills from top to bottom; rest breaks occurred while reading Mao’s

Little Red Book

of revolutionary proverbs. The atmosphere was cult-like: one group walked for two weeks to see the calluses on a Dazhai laborer’s hands. China needed to produce grain from every scrap of land, the officials learned. Slogans, ever present in Maoist China, explained how to do it:

Move Hills, Fill Gullies and Create Plains!

Destroy Forests, Open Wastelands!

In Agriculture, Learn from Dazhai!

Filled with excitement, lashed on by local authorities, villagers fanned out across the hills, cutting the scrubby trees on the pitches, slicing the slopes into earthen terraces, and planting what they could on every newly created flat surface. Despite heat and hunger, people worked all day and then lighted lanterns and worked at night. The terraces converted unplantable steep slopes into new farmland. In one village that I visited farmers increased the area of cultivable land by about 20 percent, which seems typical.

Dazhai is in a geological anomaly called the Loess Plateau. For eon upon eon winds have swept across the deserts to the west, blowing grit and sand into central China. Millennia of dust fall have covered the region with vast heaps of packed silt—“loess,” geologists call it—some of them hundreds of feet deep. The Loess Plateau is about the size of France, Belgium, and the Netherlands combined.

Loess doesn’t form soil so much as pack together like wet snow. For centuries, people in the plateau have dug caves in the loess and lived in them.

Yaodong,

as these cave dwellings are called, are quite cozy—the one I stayed in had a heated platform bed cut from a block of loess. An adjacent woodstove vented through the platform, warming the bed in winter. Looking at the

yaodong

walls that night, I realized that the room, like a scientific probe, revealed the earth’s workings. As a rule, soil has three layers: a thin scrim of dead leaves, bits of wood, and other organic matter on top; a band of dark topsoil, usually no more than a foot deep, shot through with humus (partly decomposed organic matter); and a stratum of subsoil below, lighter colored but rich with iron, clay, and minerals. Loess is different; my bedroom walls, carved from a giant heap of mashed-together grit, were uniform from top to bottom.

As every child who plays with mud knows, dust piles are easy to wash away. Silt grains “act like single particles,” said Zheng Fenli, a soil scientist at the Institute of Soil and Water Conservation, in the Loess Plateau city of Yangling. They don’t clump together firmly. If knocked free by flowing water, Zheng told me, silt grains “are very easy to transport.” Washed down steep hills, they can be carried great distances. The Huang He makes a big loop right through the Loess Plateau. It carries an enormous burden of silt—more than any other river in the world—into the North China Plain, China’s agricultural heartland.

Because the plain is flat, the river slows down. As the current falters, the silt in the water deposits on the river bottom and along the banks. The silt replenishes the soil—a main reason for the area’s farming primacy—but it also builds up the riverbed. In consequence, the Huang He rises one to three inches a year. Over time, it has lifted itself as much as forty feet over the surrounding land. When farmers harvesting wheat fields want to see the river, they look

up.

Moving high in the air, the river wants (so to speak) to overflow its banks, spilling into the North China Plain and creating a ruinous flood.

Such disasters have been a threat for millennia—“two breaks every three years and a channel change every century,” the Chinese used to say of the Huang He. But in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, erosion drove the breaks and channel changes to be more lethal. In an attempt to subdue the floods, the Qing established a corps of engineers who maintained a five-hundred-mile line of dikes, a network of spillways, locks, and dams, and an array of as many as sixteen secondary channels into which the river could be divided—a hydraulic infrastructure easily as impressive as the Great Wall, and one that was more important to the life of the nation. Not only did the system control a staggeringly complex irrigation network, it connected the river to the Grand Canal, a 1,103-mile passage between Beijing and Hangzhou (a port south of modern Shanghai) that is the longest artificial waterway in the world. Qing emperors may have spent 10 percent or more of the imperial budget on the Huang He.

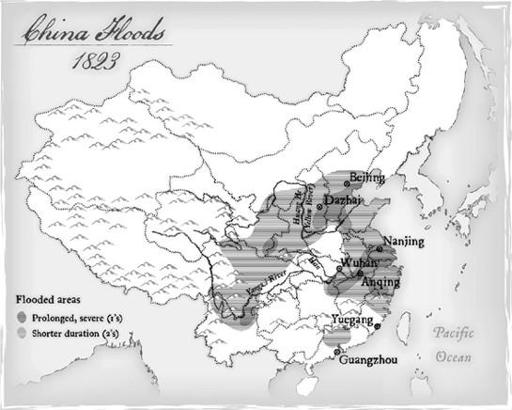

Nonetheless the system was constantly overwhelmed. As the Chinese weather bureau maps show, excess silt made the Huang He spill over its banks a dozen times between 1780 and 1850—about once every six years. All of the floods were huge. One deluge in 1887 was among the deadliest ever recorded; estimates of the dead range up to a million.

The cause of the flooding—deforestation in the Loess Plateau—was well understood. But Beijing did little about it, even though much of the land clearance had its roots in Qing policies, and the floods were blows to imperial legitimacy. The court’s failure to act was not foreordained. Neither was the myopia of the landlords who rented to the shack people. Nobody will ever know whether decisive action could have resolved the nation’s ecological problems, because it wasn’t tried. Instead the floods continued until the dynasty fell, an event the floods had helped to bring about.

Which made it all the more incredible when Mao Zedong ordered

more

land clearing in the Loess Plateau. Most of the region was already deforested, but the steepest slopes—land too steep to farm—were still covered by low, scrubby growth that held back erosion. Exactly this land was targeted in the 1960s and 1970s for conversion, Dazhai style, into terraces. The terrace walls, made of nothing but packed earth, constantly fell apart; in one Loess Plateau village that I visited after a rainfall, half the population seemed to be shoring up crumbling terraces by pounding the walls flat with shovels. Even when the terraces didn’t crumble, rains sluiced away the nutrients and organic matter in the soil. Zuitou, the village, is nestled into steep hills along the Huang He. Walking along the steep paths between

yaodong,

I could almost watch the terraces sliding into the water.

Because erosion removed nutrients, harvests in the newly planted land dropped quickly. To maintain yields, farmers cleared and terraced new land, which washed away in turn—a perfect example of a “vicious circle,” according to Vaclav Smil, a University of Manitoba geographer who has long studied China’s environment (his first book on the subject,

The Bad Earth,

appeared in 1984). Erosion into the Huang He went up by about a third during the Dazhai era, Chinese researchers reported in 2006.

The consequences were dire and everywhere apparent. Declining harvests on worsening soil forced huge numbers of farmers to become migrants. Zuitou lost half of its population. “It must be one of the greatest wastes of human labor in history,” Smil told me. “Tens of millions of people being forced to work night and day, most of it on projects that a child could have seen were a terrible stupidity. Cutting down trees and planting grain on steep slopes—how could that be a good idea?”

Beginning in the 1960s, farmers throughout China’s Loess Plateau stripped the forest and carved earthen terraces out of the hills. (

Photo credit 5.1

)

Because the loess erodes easily, every rain caused terraces to erode maintenance was a constant issue. (

Photo credit 5.6

)